Peer to Peer (P2P) lending is a hot topic at Fintech events and has received a lot of attention from academia, journalists, various international bodies and regulators. Following the Financial Crisis, P2P platforms saw an opportunity to fill a gap in the market by offering finance to customers and businesses struggling to get loans from banks. Whilst some argue they will one day revolutionise the whole banking landscape, many platforms have not yet turned a profit. So before asking if they are the future, we should first ask if they have a future at all. Problems such as a higher cost of funds, or limited ability to scale the business, may mean the only viable path is to become more like traditional banks.

Present Scale and Profitability

P2P activity has now been around for over a decade. The fastest growth has been in China, followed by the USA and the UK (total new alternative finance provision in 2016: China – $243bn,US – $35bn, UK – £4.6bn). P2P lending platforms offer an online marketplace and depend on both the external supply of investment and the demand for loans. Currently, platforms lack product diversification with their revenue deriving from origination and servicing fees. As such, platforms are extremely reliant on continuously attracting and matching loans for investors and borrowers.

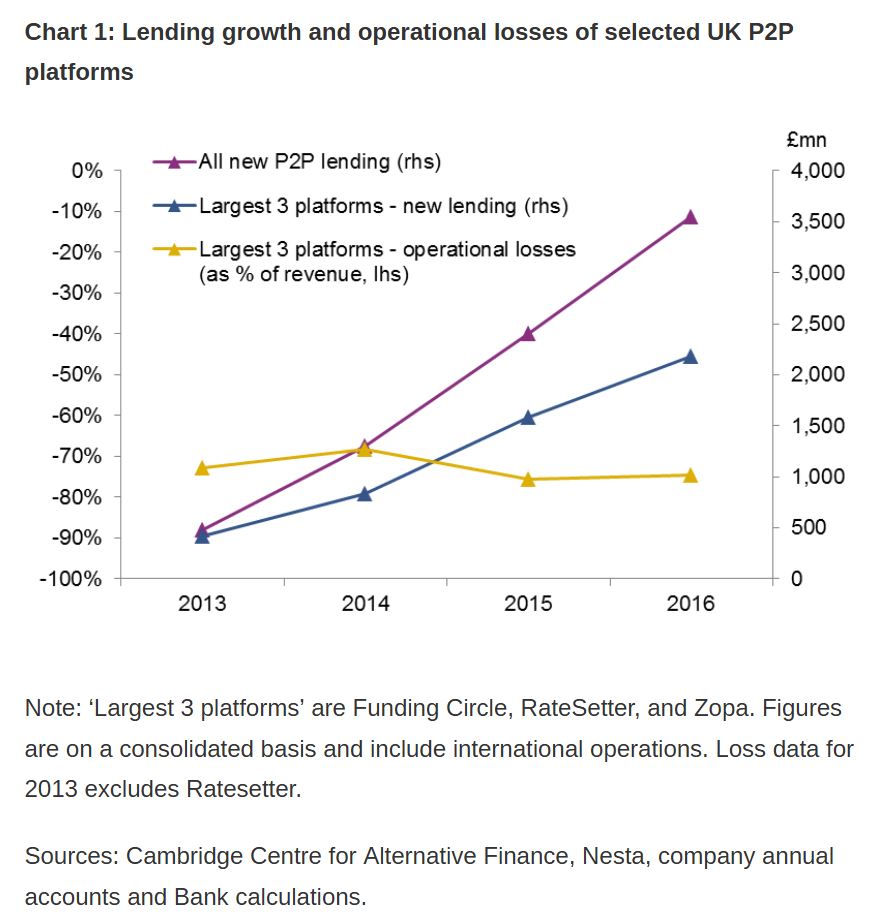

Despite having substantial lending volumes, many big UK and US platforms are still making operating losses despite their rapid growth.

In the following two sections we explore two ways in which P2P platforms could make money: first, by scaling up their existing business models; and second, by changing their business models altogether.

Scalability

It may be that some platforms have made a conscious decision to favour growth over profitability for now, with a view to realising economies of scale. Central to this business model is i) whether there is sufficient appetite for the P2P investments and loans for the platform to reach scale and ii) whether their revenues can exceed the costs, even if they achieve higher scale.

Appetite for P2P products

P2P lending is still relatively young in the UK. As matchmakers, P2P lending platforms need to keep attracting new customers from both sides of the equation in order to grow. This is not a straightforward task: for example, supply of funds might be available but there might be lack of quality borrowers. Or alternatively, they might have a slew of willing borrowers but are unable to tempt sufficient investors to finances them. A slowdown on either side affects platforms’ growth.

In the UK, P2P lending to businesses (mostly small to medium sized) is more substantial than to consumers. By contrast, in China and the US, P2P lending is mostly consumer focused. On the supply side, retail investors have dominated the market, but the role of institutional investors has been increasing.

In the past few years, the market in the UK has been growing very rapidly, with year on year new lending growth in the region of 100%. But new data from the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance suggests that although activity is still growing, the pace of that growth has slowed down considerably. In 2016, total new lending grew by roughly 50% in the UK and 20% in the US.

This, coupled with indications from some lenders that they are running into borrower constraints (i.e. their lending activity is being restricted by the low amount of potential borrowers), suggests that the traditional P2P lending model, that is widely used in the UK, may be reaching its limits. If growth rates continue to slow, platforms will find it more difficult to achieve the size necessary to fully realise their economies of scale.

One way that individual platforms may attempt to tackle this issue is through consolidation but given that the industry appears to be quite concentrated already (currently there are 3-4 major platforms that are key players), there might be only limited room for further concentration. At the end, it may be that sustainable profitability may only be achievable with a few large lenders on the market. Parallels can be drawn with other tech industries, where initially there were a number of players, but they gradually consolidated down to one or two market leaders (e.g. Google, Facebook).

Cost Structure

However, it might be the case that even following consolidation and hence larger scale, platforms still will not make money. For example, Uber is still unprofitable despite being a market leader on a large scale. And the two largest lendingplatforms in the US, who are dominant providers of P2P loans and several times larger than UK platforms, are also loss making.

The answer may lie in examining platforms’ cost structure more closely. In theory, P2P platforms have operating cost advantages; they have no legacy costs, no requirement for branch networks and lower regulatory costs. At face value, these should be lower than for traditional banks. And, unlike traditional banks, these should be largely unrelated to scale- because, like other tech disruptors, their main cost is setting up and operating a platform. That opens up the possibility of undercutting traditional banks if platforms can achieve high enough lending volumes to overcome their fixed costs and realise these cost advantages.

But we must also think about the P2P lenders’ cost of funding- i.e. the interest rate they have to offer lenders to induce them to invest. If this cost of funding is sufficiently higher, this could undo the advantage of lower operational costs. In reality, banks are able to borrow money at a lower cost, so even if P2P lenders have the slimmer cost base they may not be able to undercut banks, despite offering higher interest rates to borrowers. Just scaling up might not be enough and some platforms may need to adjust their business model altogether…

Becoming a bank-like P2P platform

In the UK, P2P lending platforms have generally begun with ‘traditional’ or ‘pure P2P’ business models. But what started as pure and simple has been continuously evolving. Platforms have already been experimenting with new business models and techniques.

Some “P2P” platforms have had success operating a ‘balance sheet’ lending model. These platforms’ business model is not pure peer-to-peer lending, because the bank itself co-invest with investors, putting their ‘skin in the game’. To do this successfully, such platforms tend to also concentrate on a particular lending market (e.g. property lending).

Other platforms might turn to traditional banking (one of the leading UK platforms is already applying for a banking licence) perhaps to diversify range of services they offer. For example, platforms will be able to offer FSCS-protected deposit accounts for savers and personal loans, car finance, and credit cards for borrowers, alongside their P2P products. Another reason is that FSCS protected deposits mean lower funding costs. Guaranteed deposits also mean that platforms can be listed on “best buy” comparison portals for savings account, creating a new potential market to tap for funds.

A natural question that follows – is there a fundamental difference for customers between banks and P2P platforms? The answer is not straightforward. Undoubtedly, platforms offer some distinct benefits for investors compared to banks– an opportunity to lend directly to businesses and retail consumers with relatively small amounts of investment, and achieve a higher rate of interest than is available from traditional savings accounts. On the other hand, banks offer deposits that are covered by the FSCS and so are less risky to P2P investors (although less risk averse investors might find that a better place to be on the risk-return trade-off).

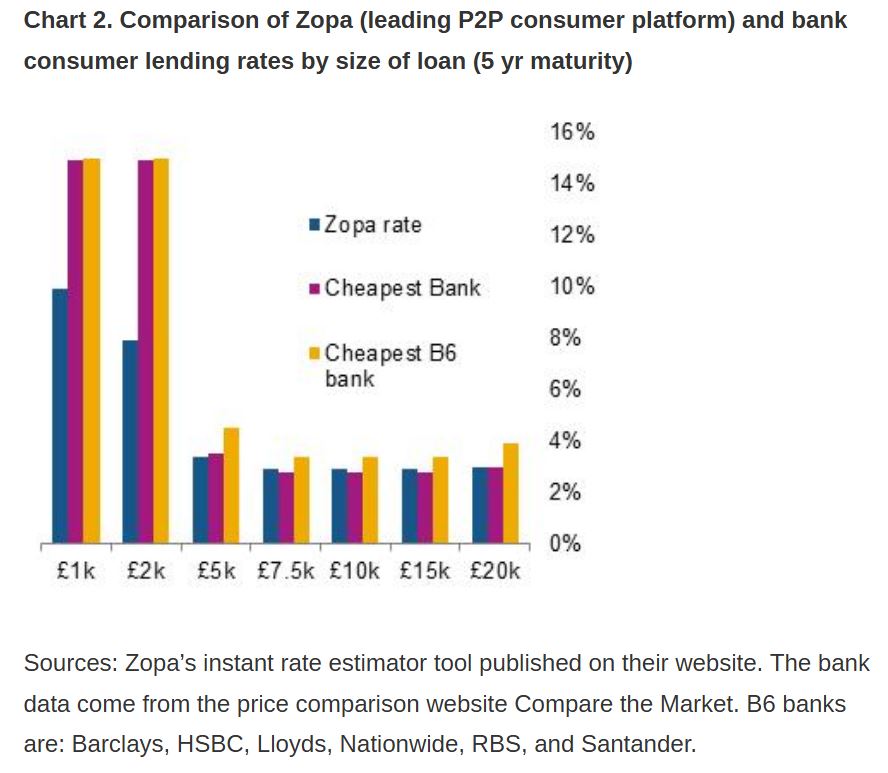

On the borrowers’ side, there may be less differentiation. Our internal analysis (Chart 2) shows that interest rates on personal loans arranged via P2P platforms are competitive but not significantly lower than the rates available from banks. The exception is low-value loans (i.e. around £1-2k), where banks’ manual processes and fixed costs, make it uneconomical for them to compete.

But P2P platforms are not the only ones adapting. As P2P lenders start to become more like banks, banks are starting to become more like P2P lenders in some respects. To counter the possible competitive threat from P2P lenders, banks have started to offer quicker and more user-friendly loan applications services (including quick, all-digital SME lending services). For a potential borrower, the difference between a P2P platform and a bank becomes less obvious. So, to stay in the game, platforms will need to compete for borrowers’ attention by offering a wider range of bank-like services.

Ironically, it might be the case that as much as the platforms have wanted to disrupt the banking model, they might need to turn towards it to grow and to achieve profitability.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the feasibility of scaling up depends on the balance of the two factors: a continuous appetite for P2P investments and loans, and whether the revenues can be higher than the costs when they do scale up.

The answer could be that platforms will need to consolidate and adjust their business models if they wish to have a significant and lasting presence in the financial system. A key part of this may be turning to banking: whether via partnering with banks or by offering bank-like services themselves. Peer-to-peer lending might be changing the world, but perhaps it will have to change itself first.

Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.