Interesting article from Deutsche Bundesbank discussing the causes of a financial crisis. High private sector debt is significant – Australia, please note – “Asset price booms are particularly harmful if they are debt-financed”!

Financial crises are costly – output and financial wealth are lost, unemployment increases, and social gaps widen. The costs may be prolonged, and they may become chronic. The global financial crisis that began ten years ago with the liquidity squeeze on global financial markets in August 2007 is still casting long shadows.

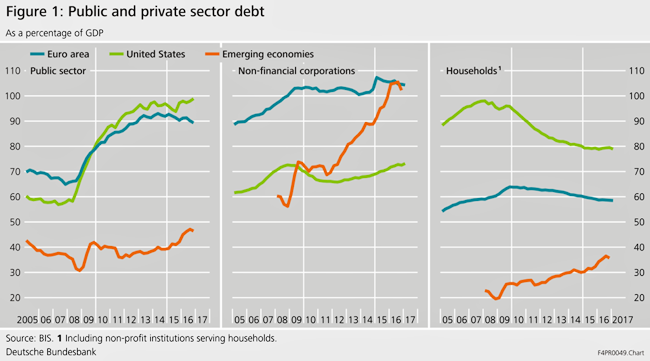

Global debt levels remain elevated. Debt levels of the non-financial sector relative to GDP stood at 220% by the end of 2016 compared with 179% a decade earlier (BIS 2017). In the aftermath of the financial crisis, risks were shifted from the private to the public sector (Figure 1). In the euro area, government debt due to the support for financial institutions went up by €488 billion, or 4.5% of GDP, between 2007 and 2016 (Eurostat 2017a). Today, in the euro area, government debt relative to GDP is about 24 percentage points higher than it was prior to the crisis (Eurostat 2017b).

The global financial crisis has had a significant impact on economic growth and unemployment. The estimated median loss varies between 4% and 9 % (Ball 2014, Mourougane 2017, Ollivaud and Turner 2014). Such output losses have also had social consequences. In the euro area, the unemployment rate went up from 9.2% in 2005 to 11.2% in 2015 (Eurostat 2017c).

Answering the question of how economies can be protected from financial crisis is thus a key challenge for policymakers. Complete “protection” against fluctuations on financial markets is not possible and would impair critical functions of markets in terms of the allocation of resources. But reducing excessive risk-taking, making crises less likely and reducing their costs should be the ambition of policymakers. In this note, I want to highlight three elements of a strategy for making future progress.First, agreed financial sector reforms need to be implemented. Enhancing the resilience of the financial system and improving buffers against unexpected shocks has been a key goal of post-crisis financial sector reforms. High levels of debt can increase the fragility of finance, make financial crisis more likely, and be an impediment to growth. In response to the global financial crisis, governments have thus set out to tackle the underlying causes of the kind of financial distress that can seriously harm the economy. Regulations have been amended in order to strengthen the financial system’s capacity to buffer shocks and to promote strong, sustainable, balanced, and inclusive growth.

Second, complementary reforms can make the reform agenda fully effective. In Europe, the Capital Markets Union is such a complementary project. Implementing the Capital Markets Union can represent a major step forward towards achieving a more resilient financial system and putting in place improved mechanisms of cross-border risk sharing in Europe.

Third, effects of post-crisis reforms need to be evaluated. Full implementation of post-crisis financial sector reforms should be followed by a structured evaluation of the effects of reforms. A structured evaluation is needed in order to assess the impact and the effectiveness of the reforms implemented and to study potential unintended consequences.

1 What are the drivers and costs of financial crises?

Financial crises have been a recurrent theme in economic history. Reinhart and Rogoff (2008b) have put together a large historical database covering eight centuries and 66 countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America, North America, and Oceania. These countries represent about 90% of world GDP. The database comprises information on a large set of economic indicators as well as indicators of crisis episodes (0/1 indicators), including external and domestic defaults, banking crises, currency crashes, and inflation outbursts. Analysing these data, the authors conclude:

“Capital flow/default cycles have been around since at least 1800 – if not before. Technology has changed, the height of humans has changed, and fashions have changed. Yet the ability of governments and investors to delude themselves, giving rise to periodic bouts of euphoria that usually end in tears, seems to have remained a constant” (Reinhardt and Rogoff 2008b, p. 53).

While fluctuations on financial markets are part of regular market processes, making crises less likely and less costly should be a key goal of economic policy. After the crisis, macroprudential policy has thus become established as a new policy area. A stable financial system fulfils its core macroeconomic functions smoothly and at all times. These functions include the efficient allocation of financial resources, the provision of risk-sharing mechanisms, and the provision of an efficient and secure financial infrastructure, including the payments system.

Yet, financial stability can be threatened if the distress of one institution or a group of financial institutions can “infect” the entire system. Channels of infection can be direct contagion through financial linkages or indirect contagion through asymmetries of information, panics, or fire sales. Through such channels, decisions by individual market participants can have external effects on the functioning of the financial system. Such “externalities” are all the greater, depending on how pronounced the risk-taking incentives are, how high the leverage of individual market participants is, how large the institutions are (“too big to fail”), how connected they are (“too connected to fail”), and how high common exposures to similar risks are (“too many to fail”). The real economy can be affected through a credit crunch when banks are forced to reduce their lending activities in response to the crisis (Brunnermeier 2009, Brunnermeier and Oehmke 2013).

One key factor that affects the stability of the financial system is the structure of finance (Bernanke, Gertler andGilchrist 1996; Gambacorta, Yang, and Tsatsaronis 2014). The larger the share of debt finance is, the larger the “financial accelerator” effects can be – seemingly small shocks can then have large and systemic implications. Economic fluctuations may become magnified and threaten the stability of the entire financial system. The channel of transmission between debt and output fluctuations can run through consumption or investment (Cecchetti, Mohanty, and Zampolli 2011, Sutherland and Hoeller 2012):

- High levels of household debt can affect the stability of the real economy through the adjustment of consumption. Evidence for the United States shows that, during the crisis, households with high levels of real estate debt cut down consumption in response to shocks to asset prices, thus amplifying the cycle (King 1994; Mian and Sufi 2014, Jordà, Schularick and Taylor 2015; Mian, Sufi and Verner forthcoming). Similar effects have been documented for other countries: The loss in consumption during the financial crisis was particularly severe in economies that experienced a large run-up of household debt prior to the crisis. And these same countries experienced the fastest increases in house prices in the pre-crisis period (Glick and Lansing 2010, Leigh et al. 2012).

- High levels of debt may also impair the ability of firms to smooth employment and investment when an adverse shock hits. High leverage has, for example, been shown to have negative effects on the performance of firms as a consequence of industry downturns (González 2013).

- High levels of public sector debt can be destabilising. Strained government finances may, for example, weaken the ability to ensure financial stability (Das et al. 2010, Davies and Ng 2011). Furthermore, high levels of public sector debt may amplify under some conditions the effects of cyclical shocks due to raising sovereign risk (Corsetti et al. 2013).

- Given the importance of the banking sector for the allocation of resources across all sectors of the economy, excessive leverage in the financial sector can be particularly harmful for the real economy. An insufficiently capitalised financial sector or banking system is thus a threat to financial stability. Adverse shocks can then set in motion a downward spiral of asset valuations and prices that ultimately threatens the solvency of financial institutions.

The destabilising effects of debt arise from its contractual features. Standard debt contracts are insensitive to the borrower’s situation. An adjustment to idiosyncratic shocks can occur only through new lending or through haircuts on existing loans after risks have materialised. In contrast, the value of equity adjusts if the borrower’s situation changes. In this sense, equity provides an ex ante risk-sharing mechanism. In other words, equity as a claim on real assets has stabilising features compared with debt as a claim on nominal assets.

Empirical studies do indeed show that excessive private (and public) sector indebtedness, asset price misalignments, international linkages of banks, and high external imbalances are drivers of financial crisis (Borio and Drehmann 2009). Furthermore, banking crises have often been preceded by real estate price booms (Reinhart and Rogoff 2008a, 2008b). This was the case in the 2008 global financial crisis, but it is also true of earlier crises in the 1970s to 1990s in, for example, Spain, Sweden, Norway, and Finland. Asset price booms are particularly harmful if they are debt-financed (Jordà, Schularick and Taylor 2015). Consequently, measures of private sector indebtedness, such as credit relative to GDP, have been identified as predictors of banking crises (Detken et al. 2014, Drehmann and Juselius 2014, Laeven and Valencia 2012). Moreover, asset price booms may be fuelled by increasing capital inflows from abroad with the potential for severe negative consequences when these capital flows stop (Kaminsky and Reinhart 1999).