The Financial Stability Board (FSB), the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI) and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) has published their final report on Incentives to centrally clear over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives.

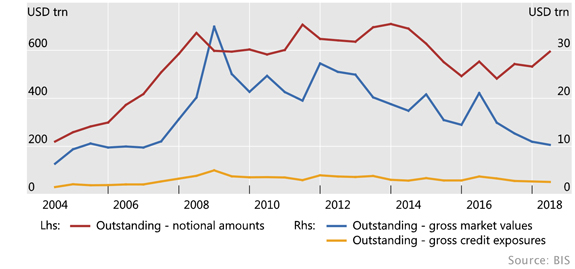

The total value of OTC derivatives was recently reported at US$595 Trillion, a massive number. The approach is been to allow the growth of these instruments, but to encourage central clearing rather than bi-lateral dealer arrangements to give greater visibility to the exposures involved. They propose capital incentives for centrally cleared transactions.

We discussed this in a recent video. This is a highly speculative market, and whilst shining more light on them may help, the more fundamental question which should be asked is why allow these to exist at all. The financial markets would be safer if they were limited to only underlying transactions, not speculative positions. At the moment, there is a risk that the derivatives markets could swamp, and bring down the normal banking system in a crisis, and that risk remains un-quantifiable. Another reason for structural separation.

The central clearing of standardised OTC derivatives is a pillar of the G20 Leaders’ commitment to reform OTC derivatives markets in response to the global financial crisis. A number of post-crisis reforms are, directly or indirectly, relevant to incentives to centrally clear. The report by the Derivatives Assessment Team (DAT) evaluates how these reforms interact and how they could affect incentives.

The findings of this evaluation report will inform relevant standard-setting bodies and, if warranted, could provide a basis for fine-tuning post-crisis reforms, bearing in mind the original objectives of the reforms. This does not imply a scaling back of those reforms or an undermining of members’ commitment to implement them.

The report, one of the first two evaluations under the FSB framework for the post-implementation evaluation of the effects of G20 financial regulatory reforms, confirms the findings of the consultative document that:

- The changes observed in OTC derivatives markets are consistent with the G20 Leaders’ objective of promoting central clearing as part of mitigating systemic risk and making derivatives markets safer.

- The relevant post-crisis reforms, in particular the capital, margin and clearing reforms, taken together, appear to create an overall incentive, at least for dealers and larger and more active clients, to centrally clear OTC derivatives.

- Non-regulatory factors, such as market liquidity, counterparty credit risk management and netting efficiencies, are also important and can interact with regulatory factors to affect incentives to centrally clear.

- Some categories of clients have less strong incentives to use central clearing, and may have a lower degree of access to central clearing.

- The provision of client clearing services is concentrated in a relatively small number of bank-affiliated clearing firms and this concentration may have implications for financial stability.

- Some aspects of regulatory reform may not incentivise provision of client clearing services.

The analysis suggests that, overall, the reforms are achieving their goals of promoting central clearing, especially for the most systemic market participants. This is consistent with the goal of reducing complexity and improving transparency and standardisation in the OTC derivatives markets. Beyond the systemic core of the derivatives network of central counterparties (CCPs), dealers/clearing service providers and larger, more active clients, the incentives are less strong.

The DAT’s work suggests that the treatment of initial margin in the leverage ratio can be a disincentive for banks to offer or expand client clearing services. Bearing in mind the original objectives of the reform, additional analysis would be useful to further assess these effects.

In this regard, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision issued on 18 October a public consultation setting out options for adjusting, or not, the leverage ratio treatment of client cleared derivatives.

The report also discusses the effects of clearing mandates and margin requirements for non-centrally cleared derivatives (particularly initial margin) in supporting incentives to centrally clear; and the treatment of client cleared trades in the framework for global systemically important banks.

The final responsibility for deciding whether and how to amend a particular standard or policy remains with the body that is responsible for issuing that standard or policy.

The BCBS, CPMI, FSB and IOSCO today also published an overview of responses to the consultation on this evaluation, which summarises the issues raised in the public consultation launched in August and sets out the main changes that have been made in the report to address them. The individual responses to the public consultation are available on the FSB website.

The five areas of post-crisis reforms to OTC derivatives markets agreed by the G20 are: trade reporting of OTC derivatives; central clearing of standardised OTC derivatives; exchange or electronic platform trading, where appropriate, of standardised OTC derivatives; higher capital requirements for non-centrally cleared derivatives; and initial and variation margin requirements for non-centrally cleared derivatives.