Where do Crypto-curriences fit it? A Central Banker’s view.

Via The Bank For International Settlements. Lecture by Agustín Carstens

General Manager, Bank for International Settlements House of Finance, Goethe University Frankfurt.

One of the reasons that central bank Governors from all over the world gather in Basel every two months is precisely to discuss issues at the front and centre of the policy debate. Following the Great Financial Crisis, many hours have been spent discussing the design and implications of, for example, unconventional monetary policies such as quantitative easing and negative interest rates.

Lately, we have seen a bit of a shift, to issues at the very heart of central banking. This shift is driven by developments at the cutting edge of technology. While it has been bubbling under the surface for years, the meteoric rise of bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies has led us to revisit some fundamental questions that touch on the origin and raison d’être for central banks:

- What is money?

- What constitutes good money, and where do cryptocurrencies fit in?

- And, finally, what role should central banks play?

The thrust of my lecture will be that, at the end of the day, money is an indispensable social convention backed by an accountable institution within the State that enjoys public trust. Many things have served as money, but experience suggests that something widely accepted, reliably provided and stable in its command over goods and services works best. Experience has also shown that to be credible, money requires institutional backup, which is best provided by a central bank. While central banks’ actions and services will evolve with technological developments, the rise of cryptocurrencies only highlights the important role central banks have played, and continue to play, as stewards of public trust. Private digital tokens posing as currencies, such as bitcoin and other crypto-assets that have mushroomed of late, must not endanger this trust in the fundamental value and nature of money.

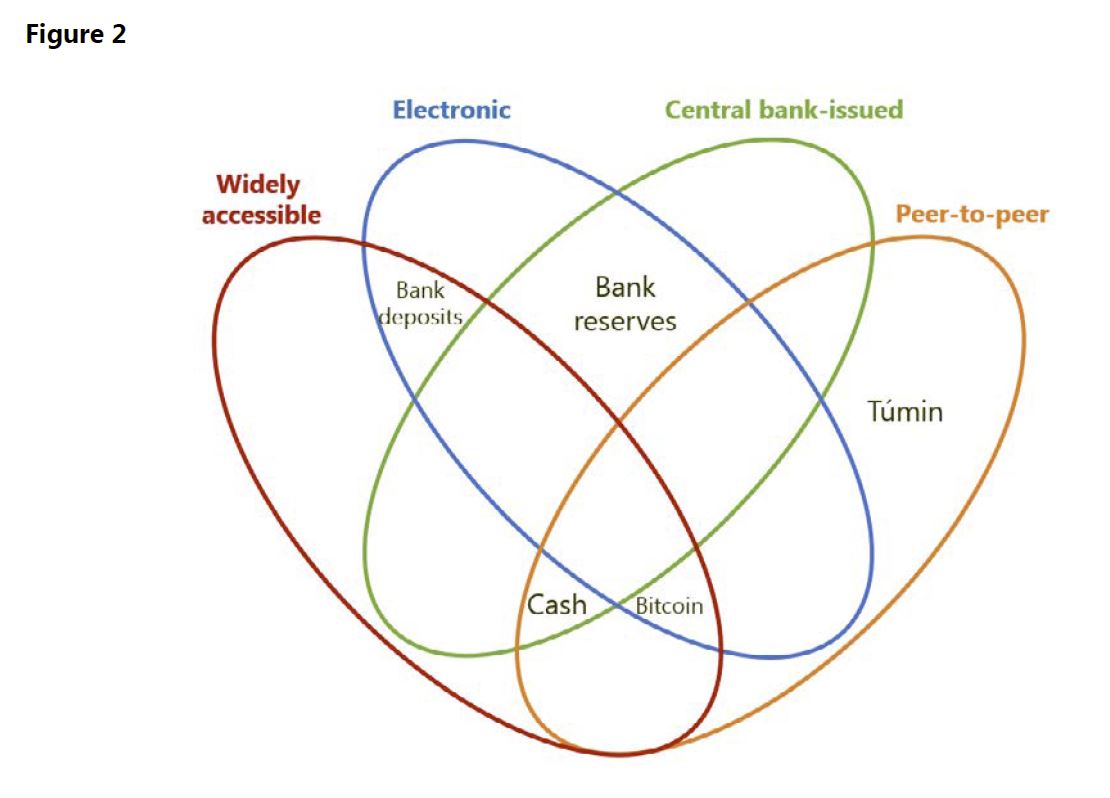

The money flower highlights four key properties on the supply side of money: the issuer, the form, the degree of accessibility and the transfer mechanism.

- The issuer can be either the central bank or “other”. “Other” includes nobody, that is, a particular type of money that is not the liability of anyone.

- In terms of the form it takes, money is either electronic or physical.• Accessibility refers to how widely the type of money is available. It can either be wide or limited.

- Transfer mechanism can either be a central intermediary or peer-to-peer, meaning transactions occur directly between the payer and the payee without the need for a central intermediary.

In conclusion, while cryptocurrencies may pretend to be currencies, they fail the basic textbook definitions. Most would agree that they do not function as a unit of account. Their volatile valuations make them unsafe to rely on as a common means of payment and a stable store of value.

They also defy lessons from theory and experiences. Most importantly, given their many fragilities, cryptocurrencies are unlikely to satisfy the requirement of trust to make them sustainable forms of money.

While new technologies have the potential to improve our lives, this is not invariably the case. Thus, central banks must be prepared to intervene if needed. After all, cryptocurrencies piggyback on the institutional infrastructure that serves the wider financial system, gaining a semblance of legitimacy from their links to it. This clearly falls under central banks’ area of responsibility. The buck stops here. But the buck also starts here. Credible money will continue to arise from central bank decisions, taken in the light of day and in the public interest.

In particular, central banks and financial authorities should pay special attention to two aspects. First, to the ties linking cryptocurrencies to real currencies, to ensure that the relationship is not parasitic. And second, to the level playing field principle. This means “same risk, same regulation”. And no exceptions allowed.