The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision today published an updated standard for the regulatory capital treatment of securitisation exposures. By including the regulatory capital treatment for “simple, transparent and comparable” (STC) securitisations, this standard amends the Committee’s 2014 capital standards for securitisations. This securitisation framework, which will come into effect in January 2018, forms part of the Committee’s broader Basel III agenda to reform regulatory standards for banks in response to the global financial crisis and thus contributes to a more resilient banking sector.

The crisis highlighted several weaknesses in the Basel II securitisation framework, including concerns that it could generate insufficient capital for certain exposures. This led the Committee to decide that the securitisation framework needed to be reviewed. The Committee identified a number of shortcomings

relating to the calibration of risk weights and a lack of incentives for good risk management.

(i) Mechanistic reliance on external ratings;

(ii) Excessively low risk weights for highly-rated securitisation exposures;

(iii) Excessively high risk weights for low-rated senior securitisation exposures;

(iv) Cliff effects; and

(v) Insufficient risk sensitivity of the framework.

The above shortcomings translate into specific objectives that the revisions to the framework seek to achieve: reduce mechanistic reliance on external ratings; increase risk weights for highly-rated securitisation exposures; reduce risk weights for low-rated senior securitisation exposures; reduce cliff effects; and enhance the risk sensitivity of the framework.

In July 2016 the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision published an updated standard for the regulatory capital treatment of securitisation exposures that includes the regulatory capital treatment for “simple, transparent and comparable” (STC) securitisations. This standard amends the Committee’s 2014 capital standards for securitisations.

The capital treatment for STC securitisations builds on the 2015 STC criteria published by the Basel Committee and the International Organization of Securities Commissions. The standard published today sets out additional criteria for differentiating the capital treatment of STC securitisations from that of other securitisation transactions. The additional criteria, for example, exclude transactions in which the standardised risk weights for the underlying assets exceed certain levels. This ensures that securitisations with higher-risk underlying exposures do not qualify for the same capital treatment as STC-compliant transactions.

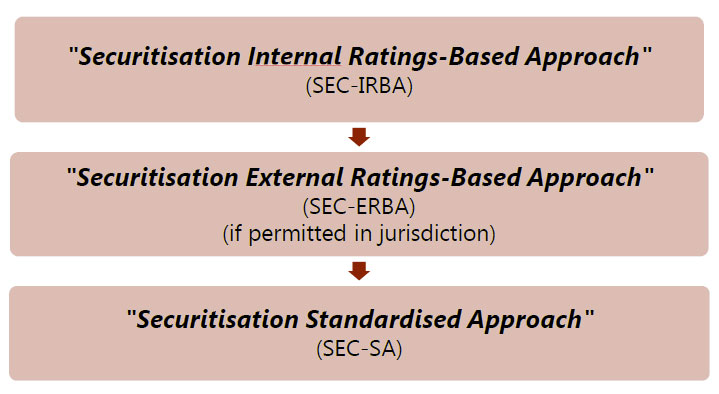

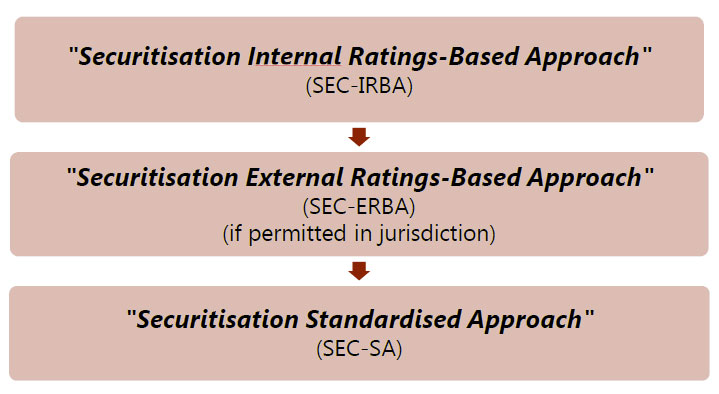

The Committee has revised the hierarchy as part of the Basel III securitisation framework, to reduce the reliance on external ratings as well as to simplify it and limit the number of approaches.

The SEC-IRBA is at the top of the revised hierarchy. The underlying model is the Simplified Supervisory Formula Approach (SSFA) and it uses KIRB information as a key input. KIRB is the capital charge for the underlying exposures using the IRB framework (either the advanced or foundation approaches). In order to use the SEC-IRBA, the bank should have the same information as under the Basel II SFA: (i) a supervisory-approved IRB model for the type of underlying exposures in the securitisation pool; and (ii) sufficient information to estimate KIRB.

A bank that cannot calculate KIRB for a given securitisation exposure would have to use the SECERBA, provided that this method is implemented by the national regulator. A bank that cannot use the SEC-IRBA or the SEC-ERBA (either because the tranche is unrated or because its jurisdiction does not permit the use of ratings for regulatory purposes) would use the SEC-SA, with a generally more conservative calibration and using KSA as input. KSA is the capital charge for the underlying exposures using the Standardised Approach for credit risk. A slightly modified (and more conservative) version of the SEC-SA would be the only approach available for resecuritisation exposures. In general, a bank that cannot use SEC-IRBA, SEC-ERBA, or SEC-SA for a given securitisation exposure would assign the exposure a risk weight of 1,250%.

The revised Basel III securitisation framework represents a significant improvement to the Basel II framework in terms of reducing complexity of the hierarchy and the number of approaches. Under the revisions there would be only three primary approaches, as opposed to the multiple approaches and exceptional treatments allowed in the Basel II framework.

Further, the application of the hierarchy no longer depends on the role that the bank plays in the securitisation – investor or originator; or on the credit risk approach that the bank applies to the type of underlying exposures. Rather, the revised hierarchy of approaches relies on the information that is available to the bank and on the type of analysis and estimations that it can perform on a specific transaction.

The mechanistic reliance on external ratings has been reduced; not only because the RBA is no longer at the top of the hierarchy, but also because other relevant risk drivers have been incorporated into the SEC-ERBA (ie maturity and tranche thickness for non-senior exposures).

In terms of risk sensitivity and prudence, the revised framework also represents a step forward relative to the Basel II framework. The capital requirements have been significantly increased, commensurate with the risk of securitisation exposures. Still, capital requirements of senior securitisation exposures backed by good quality pools will be subject to risk weights as low as 15%. Moreover, the presence of caps to risk weights of senior tranches and limitations on maximum capital requirements aim to promote consistency with the underlying IRB framework and not to disincentivise securitisations of low credit risk exposures.

Compliance with the expanded set of STC criteria should provide additional confidence in the performance of the transactions, and thereby warrants a modest reduction in minimum capital requirements for STC securitisations. The Committee consulted in November 2015 on a proposed treatment of STC securitisations. Compared to the consultative version, the final standard has scaled down the risk weights for STC securitisation exposures, and has reduced the risk weight floor for senior exposures from 15% to 10%.

The Committee is currently reviewing similar issues related to short-term STC securitisations. It expects to consult on criteria and the regulatory capital treatment of such exposures around year-end.

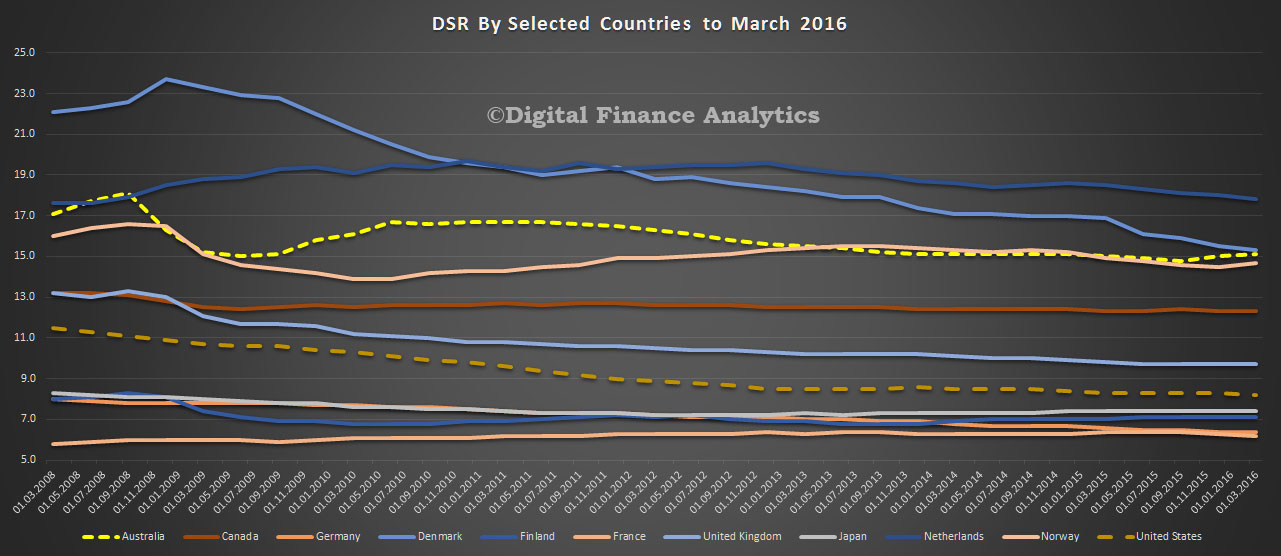

You can read our more detailed DSR analysis of Australian households, where we discuss the profile across postcodes.

You can read our more detailed DSR analysis of Australian households, where we discuss the profile across postcodes.