The Basel Committee’s Working Group on Stress Testing has published a 66 page report “Supervisory and bank stress testing: range of practices“. APRA is mentioned several times through the report, most notably about the limited disclosure of results here, compared with some other countries. Also the scope and purpose of these tests vary considerably, and the extensions into macroprudential differs. So the approach, and outputs of stress testing are very different.

The report sets out a range of observed supervisory and bank stress testing practices with the aim of describing and comparing these practices and highlighting areas of evolution. The level of data reported on supervisory stress tests reflects the differing objectives and areas of focus across supervisors.

The report sets out a range of observed supervisory and bank stress testing practices with the aim of describing and comparing these practices and highlighting areas of evolution. The level of data reported on supervisory stress tests reflects the differing objectives and areas of focus across supervisors.

It draws on the results of two surveys completed during 2016: (i) a survey completed by Basel Committee member authorities (banking supervisors and central banks), which had participation of 31 authorities from 23 countries; and (ii) a survey completed by 54 respondent banks from across 24 countries, including 20 global systemically important banks (G-SIBs). Case studies, and other supervisory findings.

There are two fundamental types of supervisory stress tests: (1) those in which the supervisors collect data from the firms and then use their own models and scenarios to assess the performance of the firms under stress (referred to in this report as either “supervisor-run” or “top-down” tests), and (2) those in which the supervisors issue scenarios and guidance to the firms, which then run their own models and report the results to the supervisor (the “institution-run” or “bottom-up” tests).

A number of authorities now use stress tests specifically for capital adequacy assessment or to inform macroprudential policies such as the countercyclical capital buffer. In some cases, stress testing frameworks aim to address multiple objectives. For example, in Canada the macroprudential stress test outcomes inform ongoing supervisory work, such as capital adequacy assessments and risk identification, prioritisation, and measurement, as well as financial stability policy initiatives. Stress testing can also be used to facilitate communication with relevant domestic and foreign parties regarding the stability of the financial system.

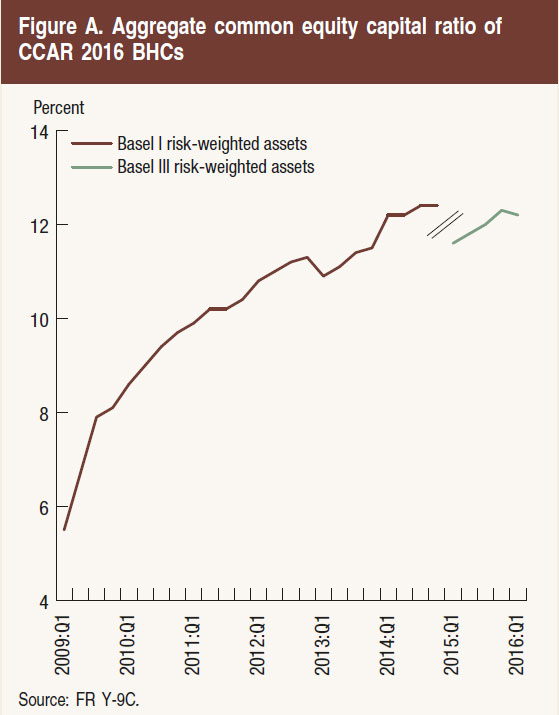

In the US, supervisory estimates of post-stress capital ratios for each bank under adverse and severely adverse economic and financial conditions are publicly released along with detailed information on losses and revenues. In the EU, for all regular EU-wide stress test exercises hitherto, the EBA Board of Supervisors decided to publish the quantitative results at the bank-level and provide comprehensive granular data for several types of portfolios on a regular basis (eg sovereign portfolios and risk weights from internal models).

In contrast, for a number of countries, only aggregate-level results are published; often this is in the context of an FSAP review. For example, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) has traditionally disclosed only the aggregate results.

APRA do not impose capital requirements directly based on stress test results, but see stress testing as a strong tool to inform supervisors’ judgments of capital adequacy. Stress testing is also expected to be reflected in banks’ capital decisions, helping banks to set target surplus thresholds and fostering greater understanding of the dynamics between capital and risk.

APRA has used stress tests results to evaluate the adequacy of banks’ recovery planning. In particular, a bank’s management actions in a stress test scenario should be consistent with and linked closely to a bank’s recovery plan in order to be credible.

In 2014 and again in 2017, the Australian and New Zealand supervisory authorities completed a coordinated banking industry stress test. Although both countries had worked together for previous banking industry stress tests, the level of engagement increased in 2014 with close coordination and collaboration on scenario design, templates, analysis and outcomes.

There is a strong link between the banking sectors in Australia and New Zealand; the four major Australian banks have significant exposures to New Zealand and their subsidiaries dominate the New Zealand banking system.

APRA was responsible for the overall coordination and execution of the stress test. There was a common scenario and set of reporting templates covering Australia and New Zealand. Timing of all stages was closely coordinated. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) provided challenge and input into the scenario and determined the specific economic parameters for New Zealand, which focused on additional agricultural risks. The RBNZ was responsible for analysing the results for New Zealand banks. Each authority engaged directly with the banks within their jurisdiction on queries and feedback throughout the process.

Ongoing engagement and communication was critical to the success of the exercise. Particular consideration was given to issues that differed between the two jurisdictions. At the highest level this involved ensuring that the economic parameters between Australia and New Zealand were realistic and consistent in a stressed environment. For example, there was discussion and challenge as to the relationship between interest rates in Australia and a corresponding level for interest rates in New Zealand.

Here is a summary of their overall observations:

- In recent years, there has been significant advancement and evolution in stress testing methodologies and infrastructure at both banks and authorities.

- Supervisory authorities and central banks continue to devote more resources to enhance the stress testing of regulated institutions, with most supervisory stress testing exercises being carried out on at least an annual basis. This is resulting in significant progress in how the exercises are performed and how they are incorporated into the banking supervision process.

- Banks have been making improvements to their governance structures, with banks’ boards, or delegated committees of boards, taking active roles in reviewing and challenging the results of stress tests, in addition to providing oversight of the overall framework.

- Banks are increasingly looking to leverage the resources dedicated to stress testing frameworks to inform the risk management and strategic planning of the bank. Stress testing frameworks are increasingly integrated into business as usual processes.

- Key challenges that remain for banks include finding and maintaining sufficient resources to run stress testing frameworks, and improving data quality, data granularity and the systems needed to efficiently aggregate data from across the banking group for use in stress tests. For national authorities, greater coordination of stress testing activities across authorities is needed, eg via the exchange information on stress test plans and results through supervisory colleges.

Microprudential use of supervisory stress tests

- Supervisory stress test results are primarily used by supervisory authorities for reviewing and validating the Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process (ICAAP) of banks and their liquidity adequacy assessments.

- Since the global financial crisis, an increasing number of countries assess capital ratio levels under adverse scenarios and use the resulting assessment for evaluating capital adequacy or required capital. However, a wide variety of practices exist.

- Certain supervisor set capital add-ons for banks by using rules-based methods based solely on stress tests (eg by benchmarking against formal hurdle rates). Those authorities which require add-ons based on stress tests mostly employ a combination of formal process and supervisory judgment. A few jurisdictions have a more rules-based treatment.

- It is less common for supervisors to use outputs from stress tests for other purposes than those related to capital/liquidity assessments. Nevertheless, some supervisors review and challenge banks’ business plans or banks’ recovery plans on the basis of stress test findings.

Macroprudential use of supervisory stress tests

- Stress tests are increasingly used to calibrate macroprudential measures and supervisory policy changes. Other macroprudential uses are early warning exercises to identify potential weaknesses of the system and enhance crisis management plans.

- Macroprudential stress tests are increasing in importance as a way of assessing the financial resilience of banking systems, as they can allow for a more direct assessment of feedback loops, amplification mechanisms and spillovers. These important effects are most frequently assessed via top down approaches.