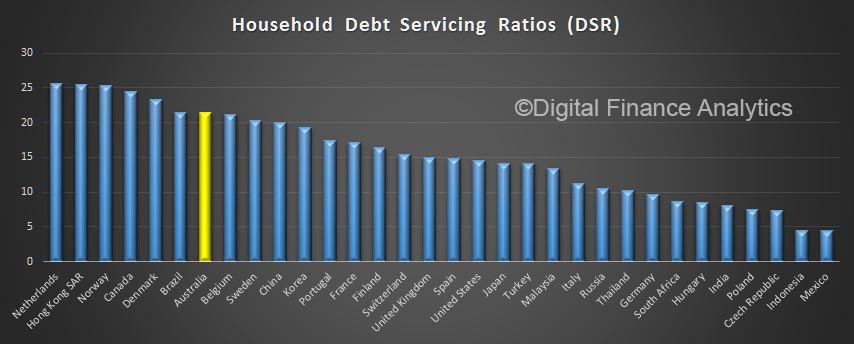

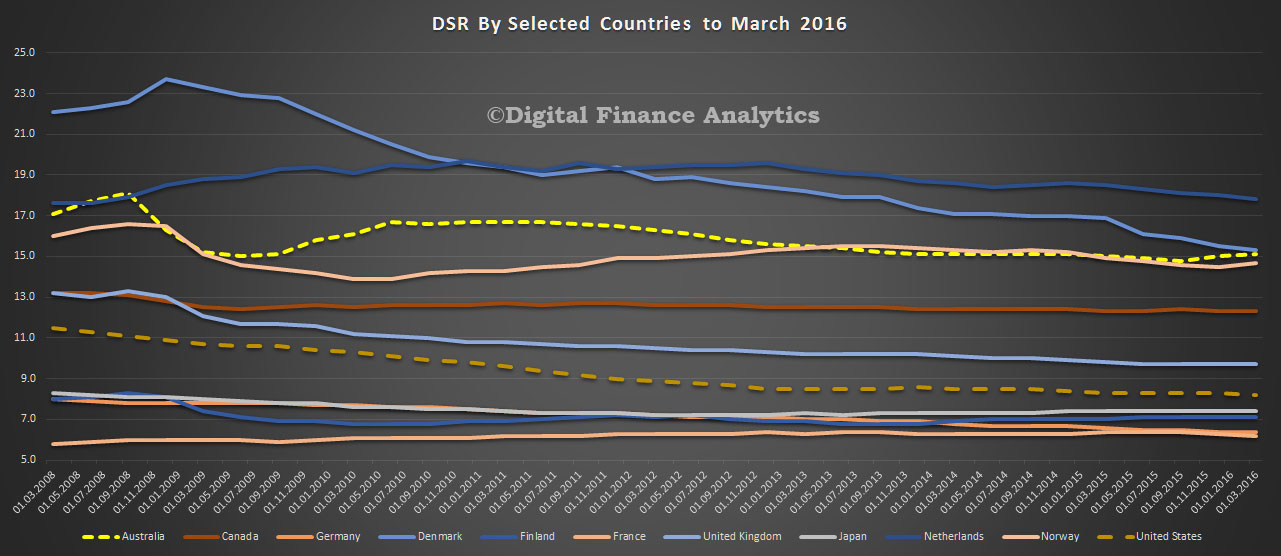

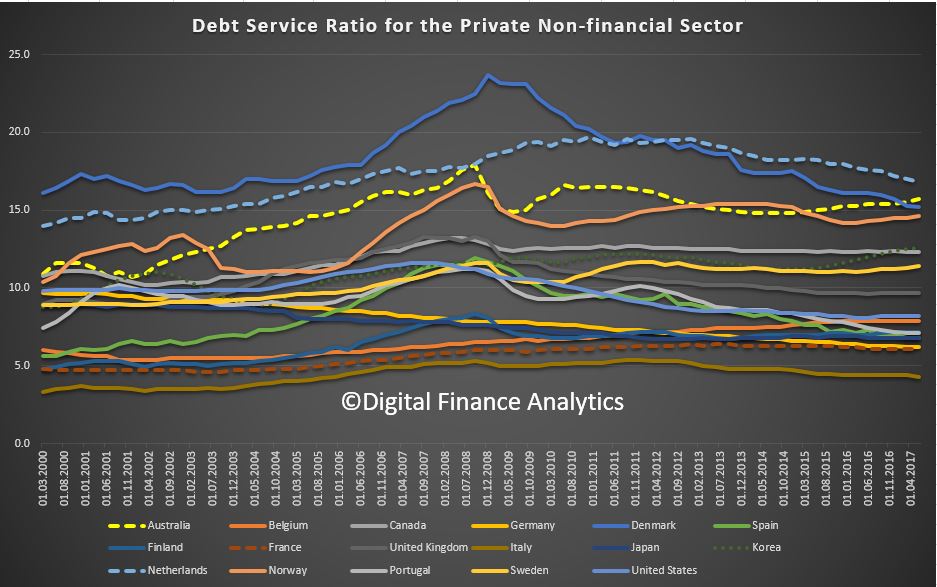

Australian Households have some of the highest debt service ratios (DSRs) in the world according to a new database from the Bank for International Settlements. In this post we overview the BIS analysis and discuss some of the results. They confirm earlier analysis that households here are highly leveraged and so at risk should interest rates rise, especially when incomes are static or falling in real terms.

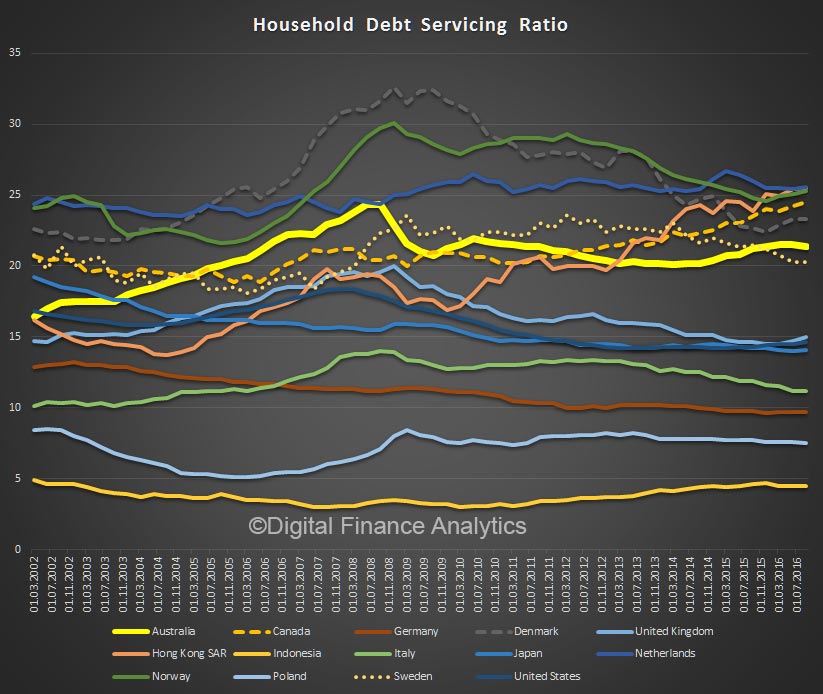

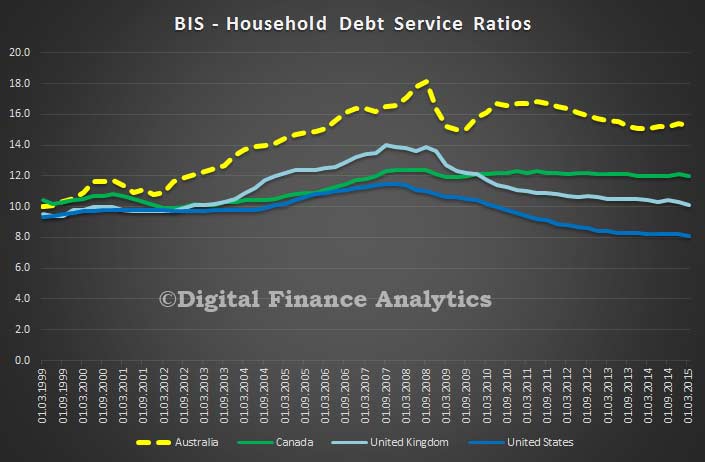

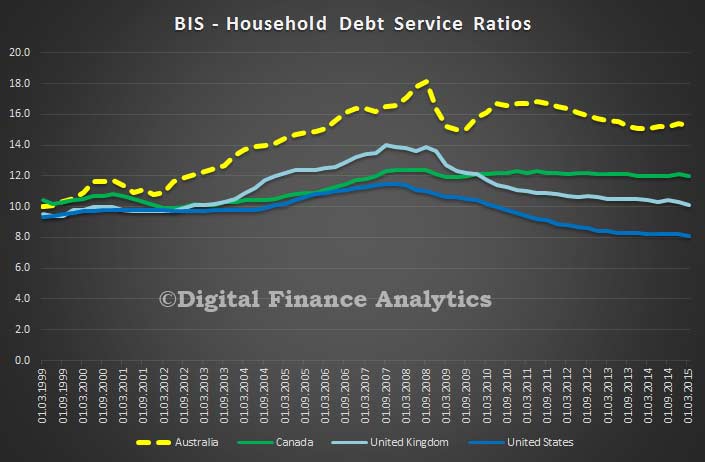

We have charted the raw outputs, for the main countries, and focused on households. If we look at the relative position of Australia, UK, Canada and USA, Australia has a higher DSR, not least because we have so far not experienced a significant drop in house prices, and mortgage lending is very high. This is consistent with previous analysis and is also the recommended measure for macroprudential purposes.

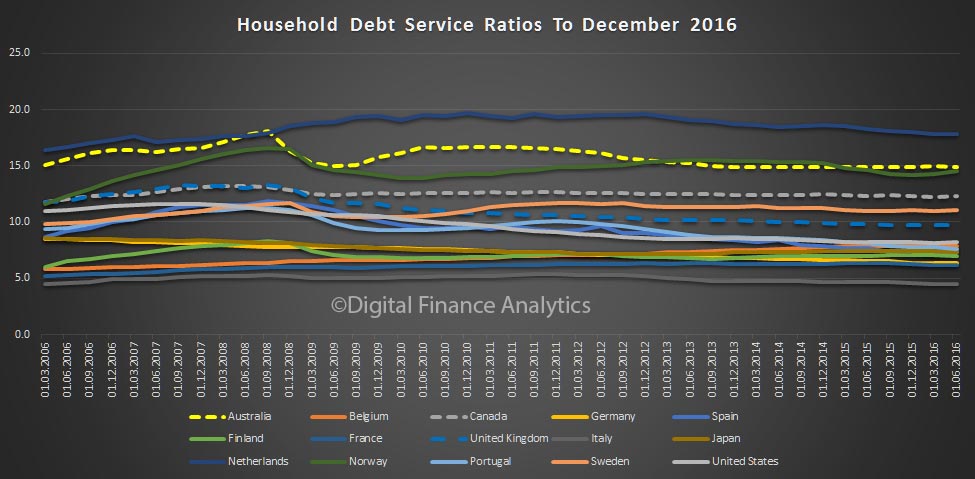

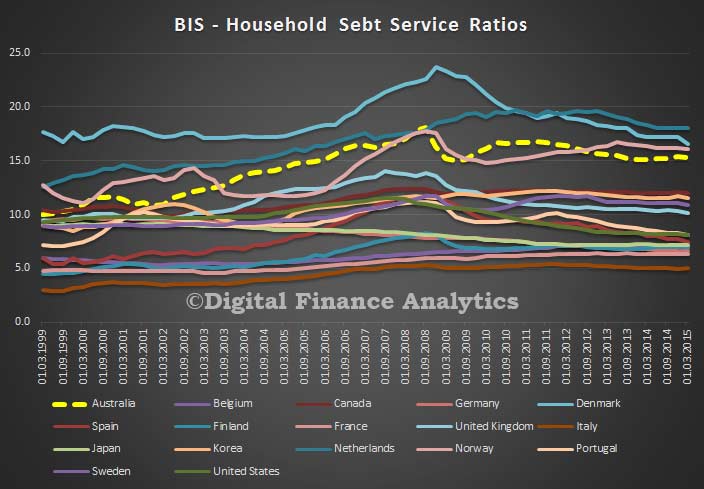

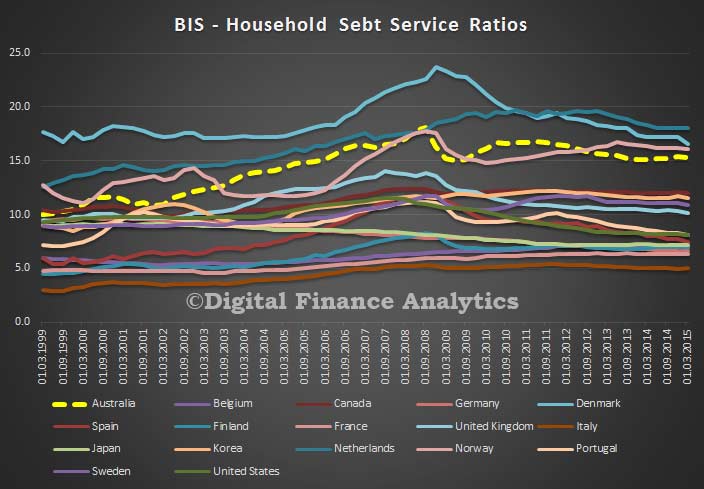

Looking more broadly at the 17 countries showing similar data, we sit fourth behind Netherlands, Sweden and Denmark. Note also the significant gap between these four and the rest of the set.

Looking more broadly at the 17 countries showing similar data, we sit fourth behind Netherlands, Sweden and Denmark. Note also the significant gap between these four and the rest of the set.

By way of background, DSRs provide important information about the interactions between debt and the real economy, as they measure the amount of income used for interest payments and amortisations. Given this pivotal role, the BIS has started to produce and release aggregate DSRs for the total private non-financial sector for 32 countries from 1999 onwards. For the majority of countries, DSRs for the household and the non-financial corporate sectors are also available.

By way of background, DSRs provide important information about the interactions between debt and the real economy, as they measure the amount of income used for interest payments and amortisations. Given this pivotal role, the BIS has started to produce and release aggregate DSRs for the total private non-financial sector for 32 countries from 1999 onwards. For the majority of countries, DSRs for the household and the non-financial corporate sectors are also available.

DSR is important, as it captures the share of income used for interest payments and amortisations. These debt-related flows are a direct result of previous borrowing decisions and often move slowly as they depend on the duration and other terms of credit contracts. They have a direct impact on borrowers’ budget constraints and thus affect spending. Despite this, in Australia there is no comprehensive reporting, just gross household debt and household repayments.

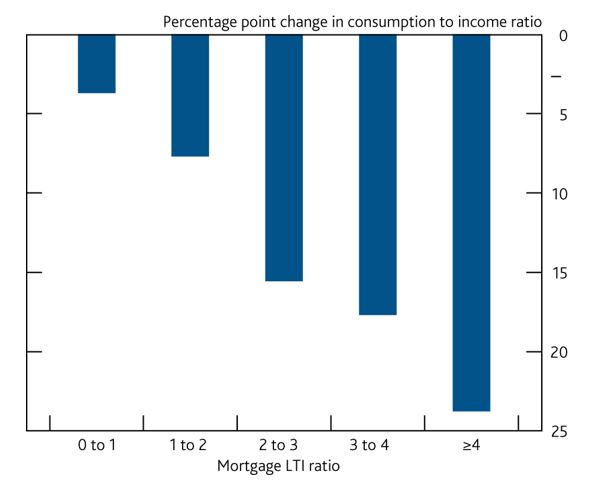

Since the DSR captures the link between debt-related payments and spending, it is a crucial variable for understanding the interactions between debt and the real economy. For instance, during financial booms, increases in asset prices boost the value of collateral, making borrowing easier. But more debt means higher debt service ratios, especially if interest rates rise. This constrains spending, which offsets the boost from new lending, and the boom runs out of steam at some point. After a financial bust, it takes time for debt service ratios, and thus spending, to normalise even if interest rates fall, as principal still needs to be paid down. In fact, the evolution of debt service burdens can explain the dynamics of US spending in the aftermath of the Great Financial Crisis fairly well. In addition, DSRs are also highly reliable early warning indicators of systemic banking crises.

BIS has developed a methodology to enable comparisons to be made across countries. The DSR is defined as the ratio of interest payments plus amortisations to income. As such, the DSR provides a flow-to-flow comparison – the flow of debt service payments divided by the flow of income.

At the individual level, it is straightforward to determine the DSR. Households and firms know the amount of interest they pay on all their outstanding debts, how much debt they have to amortise per period and how much income they earn. But even so, difficulties can arise. Many contracts can be rolled over so that the effective period for repaying a particular loan can be much longer than the contractual maturity of the specific contract. Equally, some contracts allow for early repayments so that households or firms can amortise ahead of schedule. Given this, deriving aggregate DSRs from individual-level data does not necessarily lead to good estimates. And such data are rarely comprehensive, if available at all. For this reason, BIS derive aggregate DSRs from aggregate data directly.

While interest payments and income are recorded in the national accounts, amortisation data are generally not available and hence present the main difficulty in deriving aggregate DSRs. To overcome this problem, BIS follow an approach used by the Federal Reserve Board to construct debt service ratios for the household sector which measures amortisations indirectly. It starts with the basic assumption that, for a given lending rate, debt service costs – interest payments and amortisations – on the aggregate debt stock are repaid in equal portions over the maturity of the loan (instalment loans). The justification for this assumption is that the differences between the repayment structures of individual loans will tend to cancel out in the aggregate. They also make a range of assumptions about average loan durations. You can read about the full methodology here.

The DSR reflects the share of income used to service debt and has been found to provide important information about financial-real interactions. For one, the DSR is a reliable early warning indicator for systemic banking crises.

The DSR reflects the share of income used to service debt and has been found to provide important information about financial-real interactions. For one, the DSR is a reliable early warning indicator for systemic banking crises.