There’s a common link between the many things that have promoted insecurity at work: the growth of franchising; labour hire; contracting out; spin-off firms; outsourcing; global supply chains; the gig economy; and so on. It’s money.

At first, that seems too obvious to say. But I’m talking about the way financial concerns have taken control of seemingly every aspect of organisational decision-making.

And behind that lies the rise and rise of finance capital.

Over the past three decades there has been a shift in resources from the rest of the economy to finance. Specifically, to finance capital.

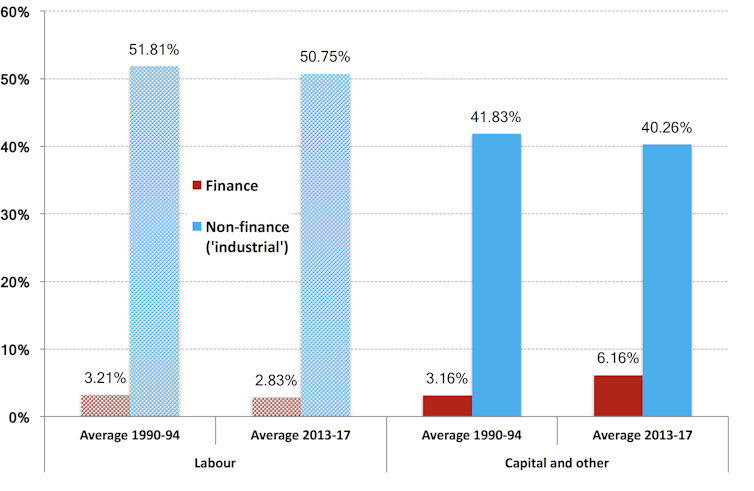

One way to see this is in the chart below. It shows the income shares of labour and capital, and the breakdown for each between the finance and non-finance (“industrial”) sectors, in two four-year periods. They were 1990-91 to 1993-94 (when the ABS started publishing income by industry) and, most recently, 2013-14 to 2016-17. (I use four-year periods to reduce annual fluctuations and show the longer-term trends. Here is more detail and explanation of methods.)

Income shares of labour and capital

The key thing to notice in the chart is that finance capital’s share of national income doubled (it’s the dark red boxes in the lower right-hand side of the chart), while everyone else’s went down.

So, over that quarter-century, the share of labour income (wages, salaries and supplements) in national income fell. In the early 1990s it totalled 55.02% — that’s what you get when you add labour income in finance, 3.21%, to labour income in “industrial” sectors, 51.81%. In recent years this fell to 53.58%. There were falls in both finance labour income (from 3.81 to 2.83% of national income) and industrial labour income.

The total share of profits and “mixed income” accordingly rose from 44.99% to 46.42%. The thing is, all of that increase (and a bit more) went to finance capital. Profits in finance went from 3.16% to 6.16% of the economy.

At the same time there has been a large increase in the share of national income going to the very wealthy — the top 0.1% — in Australia and many other countries.

This shift in resources does not reflect more people being needed to do important finance jobs. Nor is it higher rewards for workers in finance. The portion of national income, and for that matter employment, devoted to labour in the financial sector actually fell from 3.21% to 2.83%.

The economy devotes proportionately no more labour time now to financial services than it did a quarter century ago. Yet rewards to finance have increased immensely. The share of national income going to “industrial” sector profits and “mixed income” has declined.

In short, the widely recognised shift in income from labour to capital is really a net shift in income from labour, and from capital (including unincorporated enterprises) in other industries, to finance capital.

Finance matters

You may have heard about “financialisation”. It’s not really about more financial activity. It is about the growth of finance capital and its impact on the behaviour of other actors.

Financialisation has led to finance capital taking the lead shareholdings in most large corporations, not just in Australia but in other major countries (to varying degrees) as well.

This role as main shareholder and, of course, chief lender to industrial capital has driven the corporate restructuring over the past three decades that has led to greater worker insecurity and low wages growth (as I recently discussed here).

When “industrial capital” has been restructured over recent decades — to promote franchising, labour hire, contracting out, spin-off firms, outsourcing, global supply chains, and even the emergence of the gig economy — it has been driven by the demands of finance capital. Casualisation is just one manifestation of this.

Short-term logic

Now there’s no conspiracy here (or, at least, the system doesn’t rely on one). There is actually a lot of competitive mindset in the financial sector. This is just the logic of how the system increasingly has come to work. Financial returns, particularly over the short term, have become the principal (really, the only) fact driving corporate behaviour.

This has come at the expense of human considerations.

That same logic is behind resistance to action on climate change. Continuing carbon emissions are the perfect, and deadly, example of short-term profits overriding longer-term interests.

Yet even finance capital is not monolithic. There are parts of finance capital that have a longer-term perspective (“there’s no business on a dead planet”). So they are effectively in battle with those parts of finance capital for which the short term is everything. The former want governments to intervene in, for example, carbon pricing.

Policy questions

All this leaves some big questions for policymakers about how to redress the new imbalance of power.

In part, it requires changing institutional arrangements (including industrial relations laws) that in recent years have made it much harder for workers to obtain a fair share of increases in national income. It requires rethinking of how we regulate work.

But it also requires rethinking of how we regulate product markets and financial markets.

The almost global reduction in regulation of the financial sector over three decades ago has ultimately led to this imbalance. It is time to rethink all of that.

Author: David Peetz Professor of Employment Relations, Centre for Work, Organisation and Wellbeing, Griffith University