Given the RBA rate cut, concerns about poor growth, flat-lining income, structural deficits and little business investment, it is worth thinking about unconventional policies to turn the economy round. Just cutting rates does not deliver. What is needed is a longer term, properly developed structural plan.

So, a timely working paper from the IMF is worth reading. Relating Japan: Time to Get Unconventional? discusses such an approach.

So, a timely working paper from the IMF is worth reading. Relating Japan: Time to Get Unconventional? discusses such an approach.

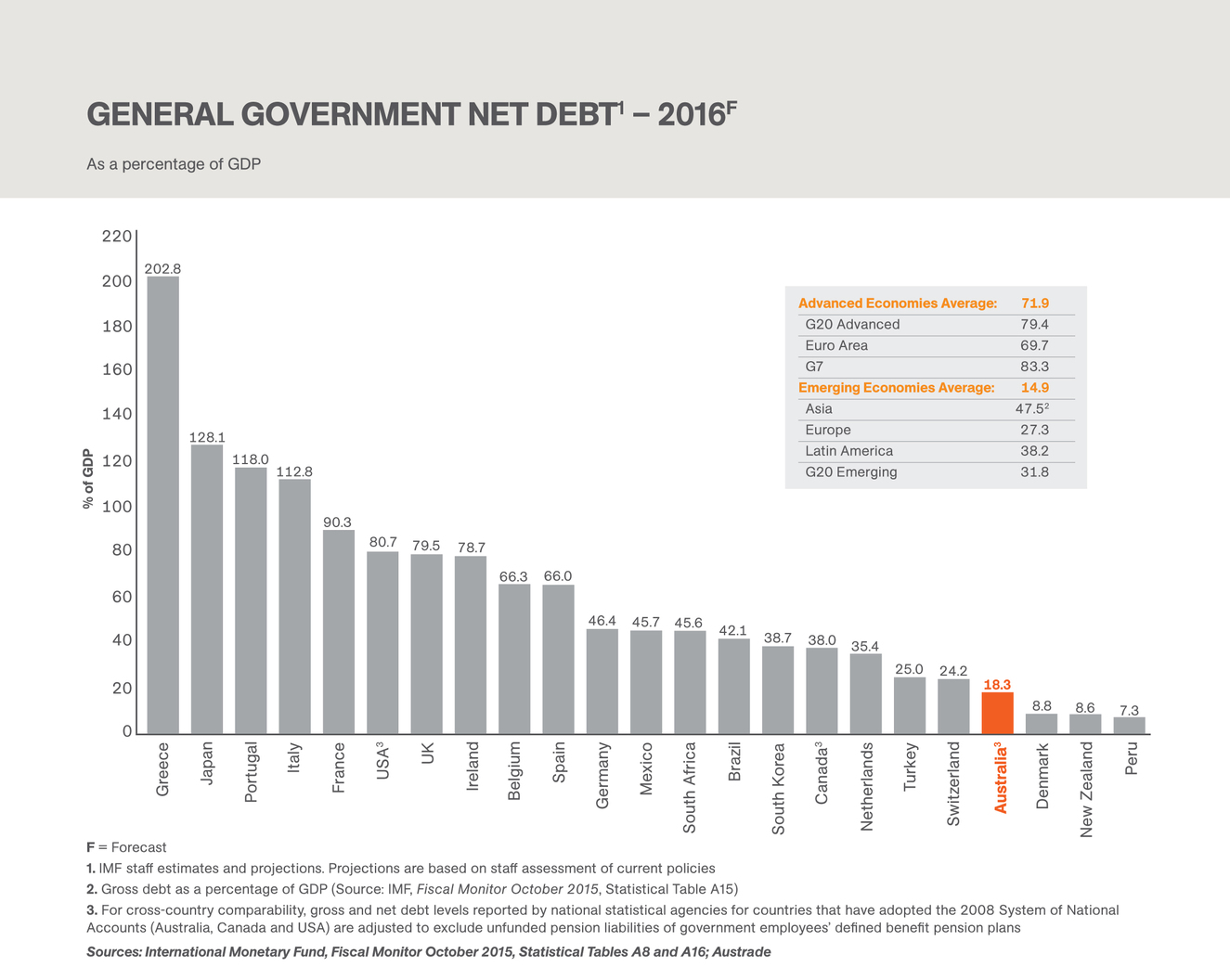

Since the bubble burst in the early 1990s, Japan has experienced deficient nominal and real GDP growth and repeated deflationary episodes. Monetary policy has been unable to get the economy out of the liquidity trap, given the Effective Lower Bound (ELB) on monetary policy rates. These factors together with repeated fiscal stimulus have led to rapid increases in the public debt to GDP ratio. Public gross debt to GDP has reached levels without precedent in peace time.

Slow wage-price dynamics amount to a missing link in the transmission of rising corporate earnings to inflation (actual and expected). Wage setting tends to be backward looking, based on recent actual inflation rather than the 2 percent target of monetary policy. Without strong efforts to resolve this market coordination blockage, attempts to raise nominal GDP growth will remain elusive.

The paper argues for a comprehensive policy package to get the Japanese economy to a higher sustainable growth path and end deflation. They call it Three Arrows “Plus”.

Prime Minister Abe’s administration came to power in December 2012 to end this economic malaise with a policy package (the so-called Abenomics) consisting of three arrows: bold monetary policy, flexible fiscal policy, and a growth strategy that promotes private investment. The objective was to jolt the economy to higher sustainable growth, positive inflation, and, through flexible policy, public debt sustainability.

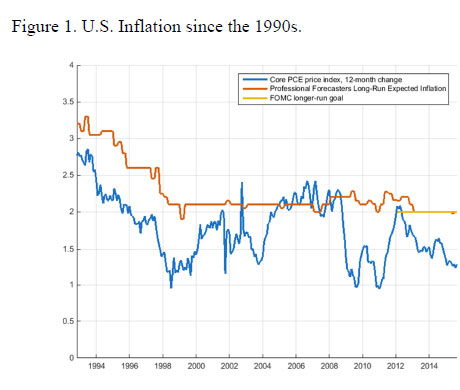

First monetary policy in Japan needs to be cast in a credible and transparent framework that is able to anchor inflation expectations over the medium term. We recommend that the BoJ moves to an inflation-forecast-targeting (IFT) framework, where monetary policy responds to deviations of the inflation forecast from the 2 percent target.

Second, Japan’s fiscal policy would benefit from a transparent framework to manage public sector balance sheet risks over the long term, while maintaining the flexibility to support monetary policy as appropriate. The challenge for fiscal policy is to preserve debt sustainability, given the large debt burden. This ultimately depends on exiting deflation, and thereby reducing long-term real interest rates as well as increasing growth. This requires a skillful fiscal policy mix that supports BoJ inflation targeting through higher public wages and transfers, while increasing VAT rates in small steps over a very extended time period to bring debt on a sustainable path. The advantage of committing to a path of small, rather than less frequent, larger-step, consumption tax hikes would be to avoid the volatility and uncertainty from large intertemporal substitution effects, and to minimize the ultimately negative effects on spending.

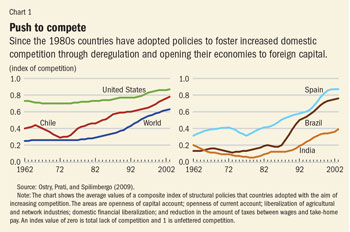

Third, to implement structural policies to reduce labor market duality, increase the labor force through foreign workers, and boost potential output. Essential to higher long-term growth is a set of structural reforms that reverses the trend in product offshoring and makes Japan an attractive place to invest again by raising future demand expectations.

Plus, the new arrow of the proposed policy package is an incomes policy for Japan to put an end to low wage growth and induce inflation (through cost-push pressures) to move in line with the BoJ target. It would build on recent measures taken by the authorities, including tax incentives for firms that raise wages, higher minimum wage increases, and moral suasion to encourage wage growth. This would be done through the wage policy of the public sector (see fiscal policy section above) and a “comply or explain” policy for the private sector. The “comply or explain” policy would be similar to the regulatory approach used in Japan, Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK in the field of corporate governance and financial supervision. The government would announce a wage inflation guideline, which companies would then either need to comply with, or explain publicly why they cannot. The wage inflation target would not be a binding law as the purpose of this policy is to reject a “one-size fits all” policy, given differences in productivity and relative prices across the economy. It should be noted that the objective of the incomes policy is not to induce changes in relative prices, higher real wages, or a reduction in competiveness but rather to move all nominal variables in line with the BoJ’s inflation target.

The U.S. incomes policy during the Great Depression was effective in ending deflation. As part of the New Deal, President Roosevelt established the National Recovery Administration (NRA) in early 1933 to help combat deflation. It established collective bargaining rights, a system of codes to set minimum wages, and to allow collusive pricing. By 1935, over half of all employees were covered by NRA codes (Lyon and others, 1935). Other anti-deflationary policies included an exit from the Gold Standard, and a large fiscal stimulus under the Public Works Administration. The US Supreme Court struck down the NRA codes as unconstitutional in 1935. The results of the NRA are difficult to evaluate, amidst all the other developments, but under the program deflation did end, and industrial production rebounded, with a 55 percent expansion, 1933–35

Generating wage-push inflation is not without risks and success is not guaranteed. For example, firms might increase hiring of non-regular workers, if there are timing and coordination problems, if “comply-or-explain” policies do not deliver sufficient compliance, or if there is the perception by firms or households that policies can be reversed. Possible declines in competitiveness and profitability—especially for labor intensive SMEs and export-oriented companies— could have an adverse impact on employment and growth in the near term. Finally, proposals to increase public wages are likely to encounter political resistance in light of ongoing fiscal consolidation plans.

Since it reinforces the three arrows of Abenomics, we call it Three Arrows Plus. An unorthodox component of the package is an incomes policy aimed directly at sluggish wage-price dynamics. We build on the authorities’ current policies by emphasizing the need for more credible and transparent monetary and fiscal frameworks that reinforce each other to reduce policy uncertainty and raise policy effectiveness. We emphasize structural reforms to end labor market duality, raise female participation, increase the labor force through foreign workers, and reform certain sectors of the economy. Although their short-term effects are uncertain, over time such reforms would raise the growth rate of potential output. The Three-Arrows-Plus package (monetary, fiscal, structural, and incomes policies) is coordinated to exploit synergies, and have the maximum chance of success.

Note: IMF Working Papers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to encourage debate. The views expressed in IMF Working Papers are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.