An IMF working paper, just released examines the impact of macroprudential policy. They conclude that implementing macroprudential does reduce the expansion of bank credit, but this is offset by a growth in non-bank credit and foreign bank lending, so the overall braking effect is less severe than expected. This substitution effect needs to be incorporated into the policy settings to deliver the desired credit growth management. Here is a summary.

Macroprudential policy is alive and kicking. It is being used actively both in emerging market economies and—following the global financial crisis—in advanced economies. It includes measures that apply directly to lenders, such as countercyclical capital buffers or capital surcharges, and restrictions that apply to borrowers, such as loan-to-value (LTV) and loan-to-income (LTI) ratio caps. Most macroprudential measures activated around the globe between 2000 and 2013 apply to the banking sector only, including borrower-based measures.

The widespread use of macroprudential policy is aimed at reducing systemic risks. Yet the use of national sector-based measures may be subject to a boundary problem, causing substitution flows to less regulated parts of the financial sector. Specifically, macroprudential policy may have the consequence of shifting activities and risks both to: (i) foreign entities (e.g., bank branches and cross-border lending); and (ii) nonbank entities (e.g., shadow banking, also referred to as market-based financing). Whereas several papers have estimated intended effects of macroprudential policies (MaPs) on variables such as credit growth and housing prices, and whether measures leak to foreign banks, cross-sector substitution effects have—to the best of our knowledge—not yet been tested empirically.

This paper aims to fill this gap. It investigates whether macroprudential policies lead to substitution from bank-based financial intermediation to nonbank intermediation. In addition, it uses event study methodology to shed light on the timing of the effects of policy measures on bank and nonbank intermediation around activation dates. Moreover, we contribute to the literature by distinguishing between the effects of quantity versus price-based instruments and lender versus borrower-based instruments, given that the effects may differ. We also check whether results differ for advanced economies (AEs) versus emerging market economies (EMEs) and bank versus market-based financial systems.

Our results support the hypothesis that macroprudential policies reduce bank credit growth. In our sample, in the two years after the activation of MaPs, bank credit growth falls on average by 7.7 percentage points relative to the counterfactual of no measure. This effect is much stronger in EMEs than in AEs. Beyond this, our results suggests that quantity-based measures have much stronger effects on credit growth than price-based measures, both in advanced and emerging market economies. In cumulative terms, quantity measures slow bank credit growth by 8.7 percentage points over two years relative to the counterfactual of no policy change.

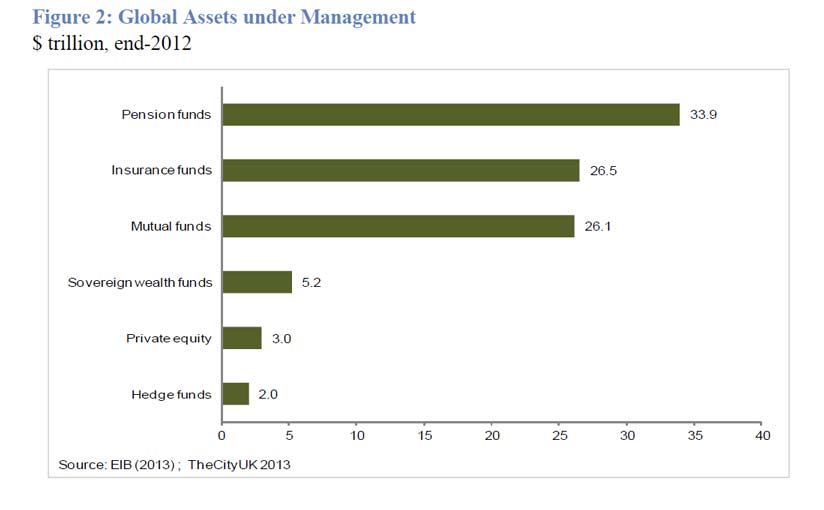

Our main contribution to the literature relates to substitution effects: we find that the effect of MaPs on bank credit is always substantially higher than the effect on total credit to the private sector. Whereas bank credit growth falls on average by 7.7 percentage points relative to the counterfactual of no measure, total credit growth falls by 4.9 percentage points on average. The reason for this is the increase in nonbank credit growth. We also find significant differences between country groups and instruments. First, substitution effects are stronger in AEs. This is in line with expectations given their more developed financial systems, with a larger role for market-based finance. Second, substitution effects are much stronger in the case of quantity restrictions, which are more constraining than price-based measures. Finally, we find strong and statistically significant effects on specific forms on nonbanking financial intermediation, such as investment fund assets.

Our paper builds on a rapidly expanding literature. While the concept of macroprudential policy can be traced back at least to the late 1970’s, it has become a common part of the policy lexicon in the first decade of this millennium. The global financial crisis has led not only to much more interest in the macroprudential approach, but also to active use of macroprudential instruments around the world.

The active use of instruments has spawned a growing empirical literature on the effectiveness of macroprudential policies, in individual country, regional and global settings. The most comprehensive study, who uses an IMF survey to document macroprudential policies in 119 countries over the 2000–13 period. They find that the implementation of such instruments is generally associated with the intended lower impact on credit, but that the effects are weaker in financially more developed and open economies.

In addition, to its intended effects, macroprudential policy may leak. Macroprudential policy may also increase crosssector substitution. A recent study by the IMF finds that more stringent capital requirements are associated with stronger growth of shadow banking. Our paper uses both net flow measures and an event study methodology to shed light on the size and timing of cross-sector substitution effects. Our empirical framework builds on work that has sought to explain credit growth, for instance to understand credit rationing and the monetary transmission mechanism. We control for macroeconomic fundamentals to filter out effects of policy on credit growth in a crosscountry panel setting.

Our results do not allow us to assess whether substitution effects reduce or increase systemic risks. A lowering of systemic risks may be expected, as risks may shift to institutions that are less leveraged and less subject to maturity mismatch. But this need not be the case, as market failures and systemic risks may also arise outside the regulated banking sector.

Overall, our findings underline the relevance of such a broad approach to monitoring and addressing systemic risks, especially for advanced economies. Earlier findings on cross-border leakages indicate that macroprudential policy should not take a narrow national perspective, as this would fail to internalize cross-border substitution effects. Our results on cross sector substitution complement these findings, and suggest that macroprudential policy should not take a narrow sectoral perspective.

Note: IMF Working Papers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to encourage debate. The views expressed in IMF Working Papers are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.