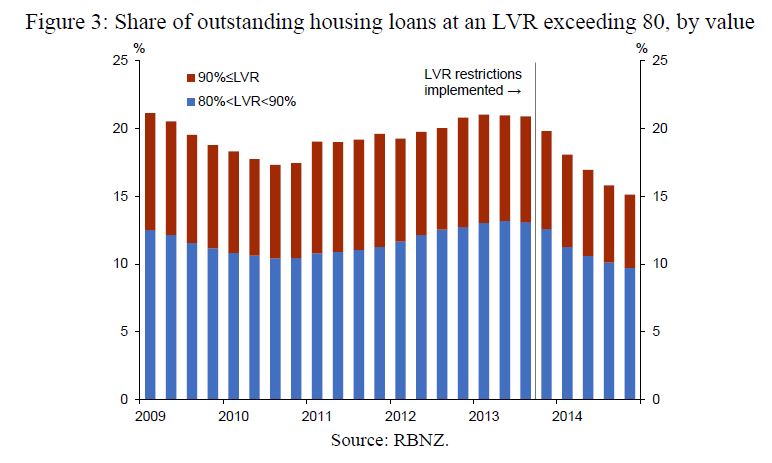

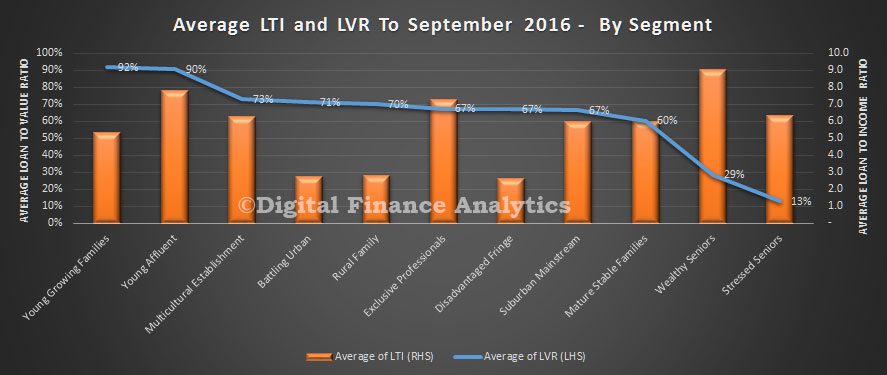

The Reserve Bank New Zealand has released a paper “Loan-to-Value Ratio Restrictions and House Prices”.

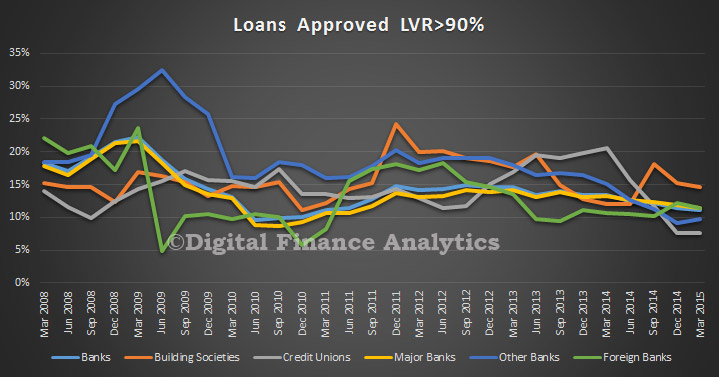

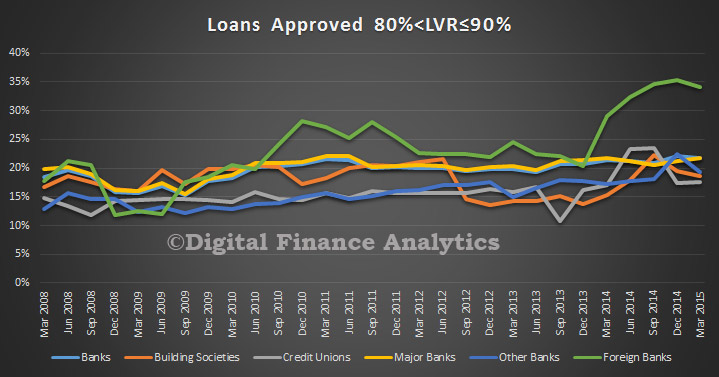

Their analysis shows that LVR limits do have an impact on home prices. But the relationship is not linear, and needs to be binding to have significant impact.

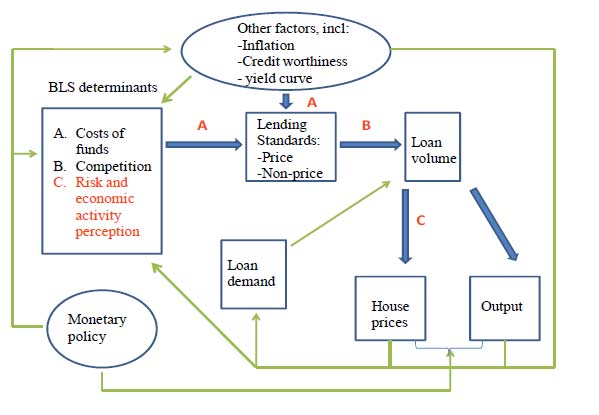

This paper contributes to the international policy debate on the effect of macroprudential policy on housing-market dynamics. We use detailed New Zealand housing market data to evaluate the effect of loan-to-value ratio (LVR) restrictions on house prices. The main challenge in identifying these effects is that housing markets are affected by a range factors over and above LVR policy. For example, New Zealand experienced a raft of policy changes and macroeconomic shocks during the periods in which LVR policy changes were implemented. Many of these shocks and policies are likely to have affected the housing market. For example, when the first LVR policy was implemented, retail interest rates were rising alongside an increasing expectation for monetary policy tightening, while the New Zealand Treasury was adjusting housing-related policies at the time of the second LVR policy. This paper uses the exemption for new builds from the LVR restrictions as a natural experiment to identify the effect of LVR policy.

We find that, over the one year window around the new home exemption, the first LVR policy (referred to as ‘LVR 1’) had a 3 percent moderating effect on house prices, and this moderating effect is broadly similar across both Auckland and the rest of New Zealand.

Interestingly, our estimates show that LVR 2 (which tightened restrictions on Auckland properties and loosened restrictions elsewhere) did not significantly stop Auckland house prices from rising. By contrast, house prices in the rest of New Zealand (RONZ) increased by 3 percent due to the relative loosening of the LVR restriction. In LVR 3, the RBNZ further tightened the LVR restrictions on property investors nationwide. The moderating effect of LVR 3 was clearly seen in Auckland with a 2.7 percent reduction in house prices. This LVR 3 effect is both statistically and economically significant, as during the same period the average house price increased by 5.8 percent.

Overall, we estimate that the LVR policies reduced house price pressures by almost 50 percent. However, the effect of LVR policy is highly non-linear. When it becomes binding, LVR policy can be very effective in curbing housing prices.