Moody’s says that on 22 March, Australia (Aaa stable) announced economic relief measures, totalling AUD66 billion ($38.2 billion, or around 3% of

GDP) in support to households, businesses and guarantees to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), in addition to a package announced previously and a set of measures aimed at supporting credit.

On 17 March, New Zealand (Aaa stable) announced a NZD12.1 billion ($7.3 billion), or 4% of GDP, stimulus package to provide immediate support to the economy and alleviate the disruption caused by the coronavirus outbreak.

Both governments have indicated that they will adopt further measures amid the rapidly deteriorating global economic outlook.

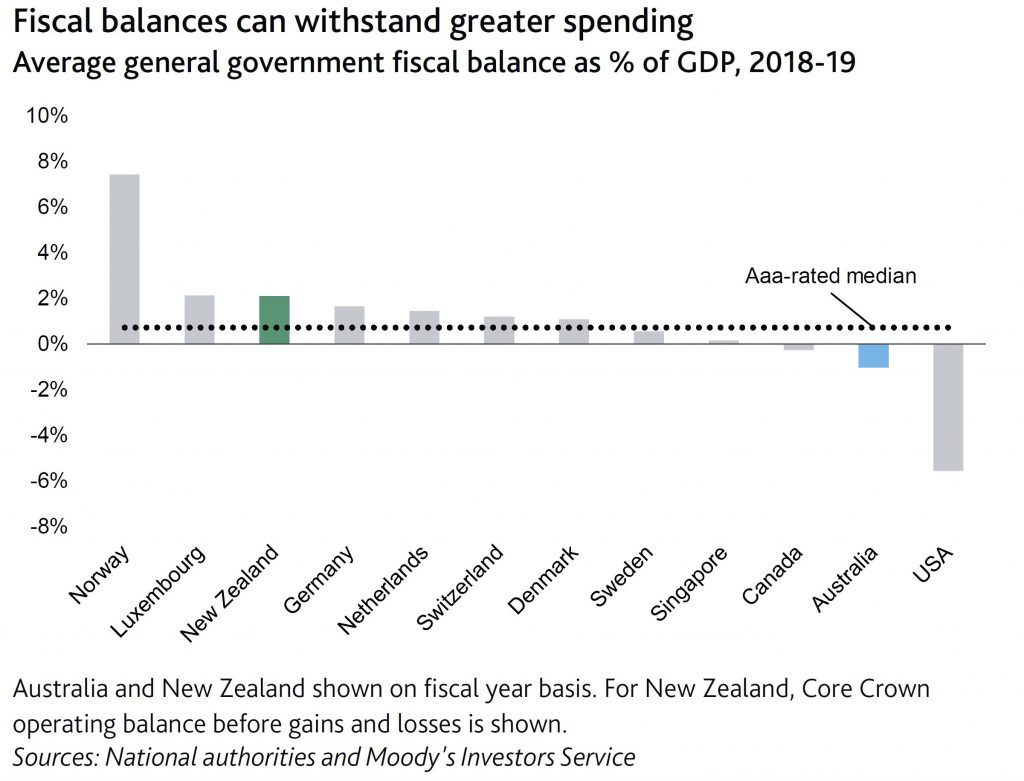

The measures highlight the strong institutional capacity of both Australia and New Zealand to develop emergency fiscal responses during an unprecedented global shock. The measures also demonstrate a high degree of fiscal flexibility that allows for larger near-term budgetary expenditure without threatening longer-term fiscal strength.

In addition to the previously announced AUD17.6 billion support to the economy, the Australian government plans to spend about AUD25 billion in support to businesses in this and the next fiscal year (the fiscal year ends in June), AUD21 billion in support to households and to offer AUD20 billion of guarantees to SMEs. Measures include a boost to SMEs’ cash flow, with upfront payments, temporary relief on creditors’ claims for financially distressed companies, a direct lump-sum payment to individuals and, specifically, to vulnerable households among other measures.

The New Zealand government will spend NZD6 billion by June 2020, as around NZD5.1 billion of the entire package is allocated as wage subsidies for affected businesses in all regions and sectors. The measure aims to stave off a significant deterioration in the labor market. The government has also announced various business tax changes to alleviate businesses’ cash flow pressures and NZD500 million in additional spending on public healthcare, much of which will go on measures that prevent transmission of the coronavirus in the country.

These stimulus packages come in addition to ongoing monetary policy stimulus in both economies. The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has cut its policy rate by 50 basis points so far in March and offered an at least AUD90 billion (0.5% of GDP) special funding facility to commercial banks, which includes an incentive to increase lending to small and medium sized businesses.

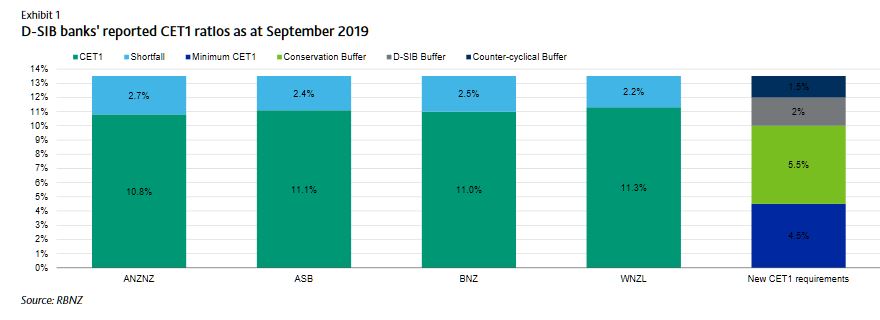

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) delivered an emergency policy rate cut of 75 basis points on 16 March, in addition to announcing a 12-

month delay to the increase in bank capital requirements, which it estimates will allow banks additional lending capacity of around

NZD47 billion (16% of GDP).

The RBA has also announced a quantitative easing program, aimed at ensuring the yield on three-year government bonds remains around 0.25%, while the RBNZ has left the door open for unconventional monetary policy including largescale asset purchases. {Subsequently Announced].

After accounting for these stimulus packages, Moody’s expects a moderate weakening in both governments’ fiscal positions, with Australia’s

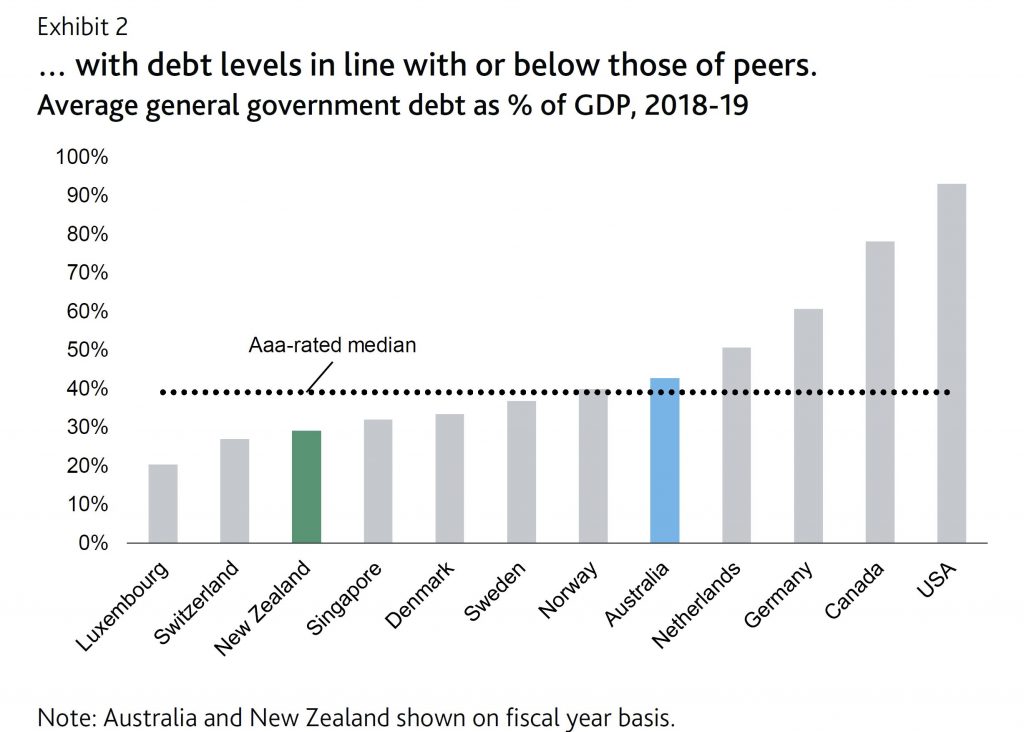

surplus turning to a deficit in fiscal 2020. New Zealand plans to fund its stimulus package with increased debt issuance and a drawdown in cash reserves, pushing net debt above the target range of 15%-25% of GDP.

Beyond these measures, weaker revenue growth because of slower economic activity and the triggering of automatic stabilizers will weaken fiscal balances. Moody’s does not view this near-term budgetary expansion by both sovereigns as significantly threatening their fiscal strength. Indeed, it highlights the flexibility and capacity that both governments possess to utilize fiscal policy to support their credit profiles amid an increasingly difficult global economic environment. Particularly for New Zealand, fiscal surpluses and debt levels below Aaa-rated peers provide ample fiscal flexibility