Climbing house prices seem to scare people but houses are relatively more affordable today than they were in 1990, it’s actually interest-rate risk that’s the bigger problem for first home buyers.

If you look at latest numbers on house prices, as a measure of affordability, they use a “median measure” – that is, the ratio of median house price to median salary. According to the latest Demographia survey, the price of the median Sydney house is 12.2 times the median salary, and it is 9.5 in Melbourne.

But it’s simply misleading to compare median-based measures of housing across different time periods in the same location. These simple median measures do not take into account differences in interest rates in different time periods.

A house in 2017 that costs nine times the median salary, when mortgage interest rates are less than 4%, is arguably more affordable than a house in 1990 that costs six times the median salary. Interest rates in 1990 were 17%.

Consider this simple example. In 1990 a first home buyer purchases an average house in Sydney priced at A$194,000. With mortgage interest rates at 17%, the monthly mortgage repayments were A$2,765 for a 30-year mortgage. But in 1990 the average full-time total earnings was only A$30,000 per annum, so the buyer’s mortgage repayments represented over 111% of before-tax earnings. In 2017 a first home buyer purchasing a Sydney house for A$1,000,000, with interest rates at 4%, is only required to pay A$4,774 every month, or 69% of their before-tax average full-time total earnings.

So, relatively, houses are substantially more affordable today than they were in 1990. The lower interest rate means the costs of servicing a mortgage is lower today than it was 25 years ago, or even 50 years ago.

However, those lower interest rates also mean today’s first home buyers face greater perils than their parents or grandparents.

Interest-rate risk

Interest rate risk is the potential impact that a small rise in mortgage interest rates can have on the standard of living of homeowners. This does not consider the likely direction of interest rates, rather how a 1% change in interest rates affects the repayments required on a variable rate mortgage.

When interest rates rise so do mortgage repayments. But the proportional increase in repayments is higher when interest rates are lower. For example, if mortgage interest rates were 1%, then increasing interest rates by another 1% will double the interest costs to the borrower. When interest rates are higher, a 1% increase in interest rates will have a lower proportional affect on their repayments.

If we go back to the example from before, the interest rate risk of the first home buyer from 1990 is much lower than that of the 2017 buyer. If mortgage interest rates rose by 1% in 1990, repayments would rise by only 5.7% to $2,923. For the 2017 buyer on the other hand, a 1% increase in interest rates would see their repayments rise by over 12% to $5,368 per month.

This has the potential to financially destroy first home buyers and, due to the high reliance of the retail banking industry on residential real estate markets, potentially create a systemic financial crisis.

Interest rate risk has an inverse relationship to interest rates – when interest rates fall, interest rate risk rises. As a result, interest rate risk has been steadily increasing as mortgage interest rates have fallen. Given that we have record low interest rates at the moment, interest rate risk has never been higher.

Putting it all together

Compounding all of this is the general trend of interest rates.

In 1990 mortgage interest rates were at a record high and so our first home buyer could reasonably expect their repayments to decrease in the coming years. They could also reasonably expect that, as mortgage interest rates fell, demand for housing would increase (all else being equal) and so would house prices, generating a positive return on their investment.

But our 2017 first home buyer is buying when interest rates are at record lows. They cannot reasonably expect interest rates will fall or for their repayments to go down in future years. It’s also unlikely that house prices will increase as they have for previous generations.

So while the current generation of first home buyers find housing much more affordable than their parents, they face substantially higher interest-rate risk and a worse outlook for returns on their investment. If we wish to address the concerns of first home buyers we should look into these issues rather than exploiting misrepresentative median-based measures of house affordability.

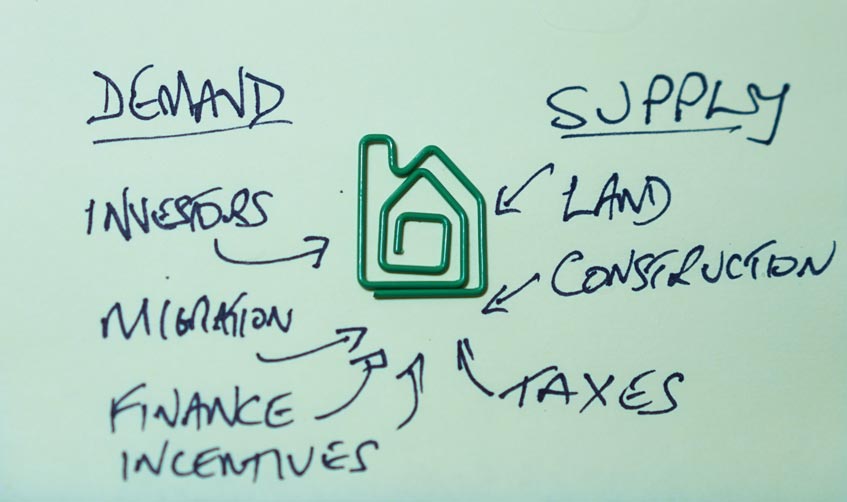

Apart from addressing issues with the supply of housing, governments need to investigate ways to reduce interest rate risk over the longer term.

Author: Associate Professor, University of Sydney

——————————————————-

We would make the point that income growth is static or falling, prices relative to income are higher in many urban centres, and the banks are dialing back their mortgage underwriting criteria (especially lower LVR’s, reductions in their income assessment models and higher interest rate buffers). All of which work against lower interest rates, which are now on their way up, so this article seems myopic to us!

However, we agree the interest rate risk is substantial, and more than 20% of households are in mortgage stress AT CURRENT LOW Rates. We also think the risks are understated in most banking underwriting models, because they are based on long term trends when interest rates were higher.