There’s a lot in the Productivity Commission’s landmark 722-page table-thumper of a report into Australia’s superannuation system, completed after nearly three years of invesigation. For now, I’ll make three comments.

The Commission gets the industry

First, it’s a very valuable report. The Productivity Commission (PC) has undertaken a deep analysis of the superannuation industry and collected a range of information that was previously unavailable. The research has been conducted with considerable care and diligence, backed by insight. I am confident the PC understands the industry. The report is a great resource that will probably be cited for years to come.

Yet sets itself against the industry…

My second comment relates to the gusto by which the PC has called out shortcomings of the system, and advocated for key changes. While the PC is aiming to be constructive, the report reads as quite critical.

It seems guilty of overstatement for dramatic effect, which I fear may inhibit moving forward. Many report headings read as if they are brickbats. It headlined two of its diagrams: “the character of member harm”. It sets the tone on page five:

The system delivers good outcomes for many members, but not all. The industry’s peak body submitted that “the Australian superannuation system is not broken, and is in fact a world class private pension system”. The evidence suggests otherwise.

In my view, the system is better described as being very good with room for improvement.

The PC has raised the ire of the industry, which will create a barrier to change as the advocacy ramps up.

While most of its recommendations are sensible, the idea of a panel selecting a “best-in-show” shortlist of 10 default funds is controversial.

The recommendation is being attacked on its potential shortcomings, when the debate ought to be around whether it is the best option among a set of imperfect alternatives. The simpler question of whether the PC’s recommendation is better than the current system is not being debated.

We are travelling down an adversarial path unlikely to build consensus around what needs to happen.

…and raises more important questions

Third, the PC has recommended further investigations going beyond its terms of reference. I will finish by focusing on Recommendation 30: an independent public inquiry into the role of compulsory superannuation in the broader retirement incomes system, including the net impact of compulsory super on private and public savings.

Surprising, there is no established position on how effective superannuation has been in working toward Australians supporting themselves in retirement. It is an open question whether the costly tax concessions attached to super provide an overall benefit to Australian society.

The Commission also wants the inquiry to examine who is hurt and who is helped by compulsory superannuation, both over time and at any point in time.

The PC is calling for an examination into the amounts being contributed into super, given that it called for the inquiry to be completed ahead of the the next scheduled increase in the compulsory contribution rate from 9.5% of salary to 10% in June 2021.

The PC was limited to examining the efficiency of the system under current policy settings. But the settings themselves are arguably the greatest barrier to the efficiency of the system, and its ability to serve the public. An inquiry into super’s place within the broader retirement income system would be an opportunity to work out how it can serve us best.

Too often the discussion is framed as if superannuation is the only resource supporting members through retirement. The call to lift the compulsory levy from 9.5% to 12% – some have argued for 15% or even 20% – epitomises this myopic perspective.

The reaction to a recent Grattan Institute report (Money in retirement: more than enough, November 2018) addressing various aspects of system design and questioning the need to increase the levy was revealing.

Grattan was lambasted for their stance, unfairly in my opinion. Much of the criticism came from those with a stake in seeing the levy increased, and mostly danced around the fringes of the argument. All this is indicative of an inability to have a thoughtful discussion over important policy issues.

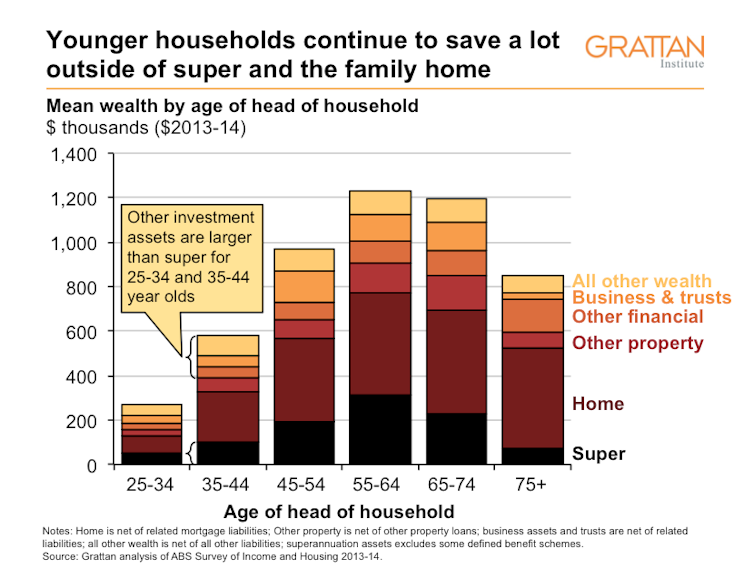

Superannuation interacts with many other aspects of retirement support, including the social security system (specifically the aged pension), the tax system, other assets held by individuals, in particular whether they own a home, and personal circumstances.

Money siphoned off into super to support spending in retirement comes at the cost of lower spending power during the working years.

Placing more in superannuation might be entirely right for some, but might come at a cost for others.

They are good questions

The first interrelation between super and other features of the system needs to be better understood. There are various flags pointing to inconsistencies.

Claims that people are not saving enough for retirement do not gel with many retirees taking money out of super at the minimum rates.

Meanwhile the social safety net is substantial. The (single) aged pension of A$24,824 is 86% of the Association of Superannuation Funds “modest” living standard up to age 85, and 91% of it after age 91. And Australians have access to affordable health care.

Home ownership is a key determinant of capacity to support oneself through retirement, and it is only heightened by it being excluded from the pension means test. There can be a huge gap between retirees who own their home and those who do not.

Many low income earners struggle to establish themselves in life, yet are forced to invest in super, on which they may be taxed at greater rate than their current income tax rate.

The super system is designed around individuals, yet most people operate within households.

The PC is right to call for an inquiry into the entire system design. It would be an opportunity to examine the interaction of super with everything else, whether it is doing what it should, and whether it is treating different types of Australians in the way we would want.

Author: Geoff Warren, Associate Professor, College of Business and Economics, Australian National University