Even though this year’s budget is pretty good politics and reasonable economics, on almost every front, it is a missed opportunity to be bold.

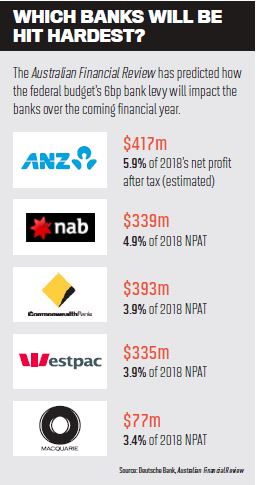

Last year’s budget was a bank-bashing bombshell, with 4-5% of profits for five of Australia’s biggest banks yanked away, not for financial stability reasons, but because, as Treasurer Scott Morrison hinted at the budget press conference, people don’t like the banks very much.

With that populist mission accomplished, this year’s budget is more mundane.

The much-vaunted return to surplus is now planned for 2019-20 at just 0.1% of GDP. In 2017-18 we are told to expect a deficit of 1% of GDP ($18.2 billion). That’s before the forecast 3% real GDP growth from 2018-19 onward kicks in. An heroic assumption.

Compare that to an actual of 2.1% in 2016-17. That topline forecast is not insane, but it is certainly bullish. One is tempted to ask the Treasurer whether he would bet a year’s salary that real GDP will be above 3% compared to below that. I suspect he wouldn’t.

A new personal income tax plan

Having previously introduced, but not wholly managed to get through the Senate, a 10-year plan to reduce the company tax rate from 30% to 25%, this year the government has a seven-year “Personal Income Tax Plan”.

Under the “PIT plan” (pun absolutely intended) the number of tax brackets will be reduced from five to four. By 2024-25 the tax-free threshold will remain at $18,200 and a 19% tax rate will apply up to income of $41,000, at which point the 32.5% rate will kick in. The top marginal rate of 45% will apply to incomes above $200,000.

One good thing the plan does address (at least in part) is “bracket creep,” where wage growth coupled with fixed tax thresholds, leads taxpayers to pay more. Under the new plan, 94% of Australians will pay no more than a 32.5% marginal tax rate. That compares to 63% of Australians who pay that rate or less, under existing policy settings.

In terms of tax relief, it’s relatively modest. A person earning $50,000 will be $530 better off in 2018-19. Because of changes to the Low and Middle Income Tax Offset, this falls to $215 for someone earning $120,000 (and less still beyond that).

Now $530 post-tax dollars, for someone on $50,000 a year, isn’t nothing. But it doesn’t really make up for wage growth so sluggish (2.2% on average last year) that it barely keeps up with inflation.

This is all part of the government’s newly announced, but thoroughly leaked, mantra that taxes should be no more than 23.9% of GDP. The rationale is, as the budget papers put it “so we do not unfairly burden Australians, nor allow taxes to chase ill-disciplined spending”.

In some sense that’s a fair point, but the 23.9% is completely unscientific. It appears to be the average of what tax as a share of GDP was during the Howard government, which has left most economic commentators wondering “so what?”

The black economy and superannuation

There’s a “crackdown” on the black economy with a $10,000 limit on cash transactions. Who knows how that will be enforced. Perhaps our good friends the banks will start complying with anti-money laundering provisions.

In any case, I prefer a $0 limit on cash transactions by transitioning over three years to a cashless Australia. That would likely raise $5-6 billion a year every year, maybe more.

The sneakiest thing of all is taxing tobacco 12 weeks earlier when it leaves the warehouse, rather than at present upon entry into Australia. That will boost tax receipts once, and once only, in 2019-20 by $3.27 billion. Without that timing trick the return to surplus would be pushed back a year to 2020-21.

Having attacked retirement savings last year, the government is now “reuniting Australians with lost super”. Hard to be against that, but hard to get too excited either. Exit fees on superannuation accounts will also be banned, which is a very good idea and should help consolidation of accounts.

One step better would be making it a net zero cost to transfer all banking arrangements (mortgage, accounts, credit cards, etc) from one bank to another, through a mandate on banks and a subsidy for customers. That would help with competition in the banking sector, which has come under recent scrutiny.

Another small but sensible initiative is increasing the Pension Work Bonus from $250 to $300 per fortnight, which permits pensioners to earn up to that amount without affecting their pension eligibility.

On a more disappointing note there is a reasonably large amount of fanfare but very little substance about “backing regional Australia”. There is $200 million for a third round of the Building Better Regions Fund to support infrastructure on top of the $272 million from the Regional Growth Fund.

That’s fine but falls well short of a systematic plan for regional infrastructure and does not address regional unemployment, particularly youth unemployment, in a meaningful way. Tackling that would require the kind of place-based policies like targeted wage subsidies and reduced payroll taxes that I have advocated before.

There are a host of so-called “integrity measures” to do with taxation. There’s the oft-talked about tightening of thin capitalisation rules, whereby companies load worldwide debt onto an Australian entity to increase interest charges in Australia, instead of in low taxing jurisdictions like Ireland. This is in addition to other attempts to get multinationals to pay more tax. These are more likely to get multinationals to pay lawyers more, but it’s now customary padding in every budget.

The forecasts are pretty rosy in this year’s budget, but they always are. Overall, it’s a hard budget to hate, and a hard budget to like. But it is a classic political pre-election budget.

Author: Richard Holden, Professor of Economics and PLuS Alliance Fellow, UNSW

Rate rises and competition

Rate rises and competition