In its superannuation policy for the 2013 election, the Government stated that it would review both the minimum withdrawal amounts for account-based pensions and the regulatory barriers currently restricting ‘the availability of relevant and appropriate income stream products in the Australian market’. The Treasury has now released the outcomes of the review.

The paper says the current annual minimum drawdown requirements are consistent with the objective of the superannuation system to provide income in retirement and should be maintained.

An additional set of income stream rules should be developed which would allow lifetime products to qualify for the earnings tax exemption provided they meet a declining capital access schedule.

In regard to the existing minimum drawdown rules:

1. The current annual minimum drawdown requirements are consistent with the objective of the superannuation system to provide income in retirement and should be maintained.

2. The Australian Government Actuary should be asked to undertake a review of the annual minimum drawdown rates every five years and advise the Government to ensure that they remain appropriate in light of any increases in life expectancy.

3. Any other changes to the minimum drawdown amounts should only be considered in the event of significant economic shocks and based on further advice from the Australian Government Actuary.In regard to the development of other annuity-style retirement income stream products:

4. An additional set of income stream rules should be developed which would allow lifetime products to qualify for the earnings tax exemption provided they meet a declining capital access schedule.

5. The alternative product rules should be designed to accommodate purchase via multiple premiums but additions to existing income stream products should continue to be prohibited.

6. Self-Managed Superannuation Funds (SMSFs) and small Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) funds should not be eligible to offer products in the new category.

7. A coordinated process should be implemented to streamline administrative dealings with multiple government agencies.Minimum drawdowns in practice

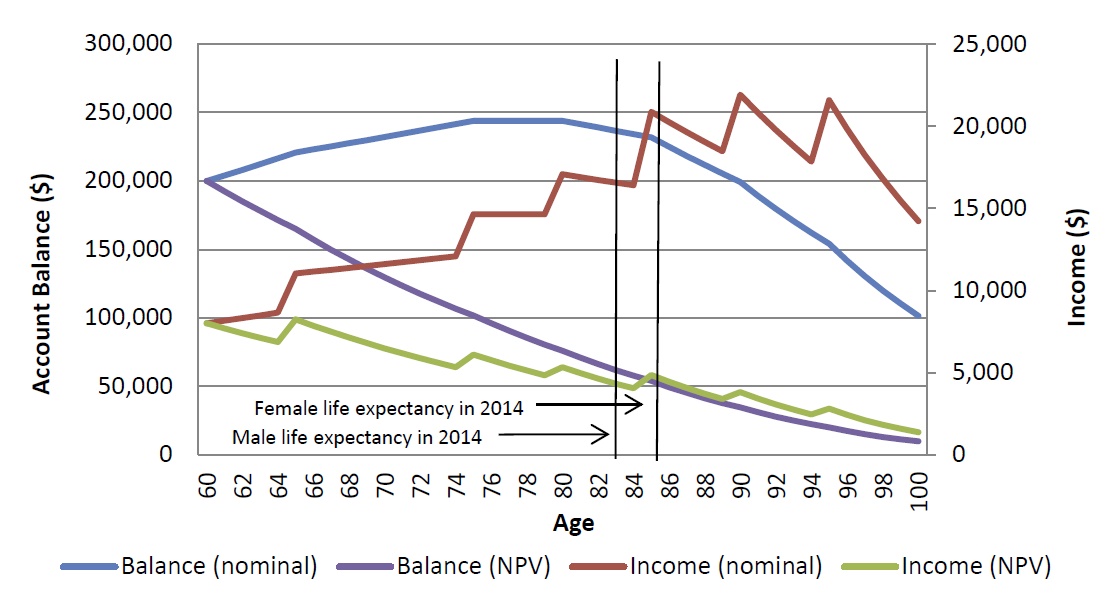

Chart 1 (below) illustrates a drawdown scenario for male and female retirees commencing an account-based pension with a balance of $200,000 at age 60 and drawing down at the minimum payment amounts with investment returns of 6 per cent per annum. The chart shows the account balance at various ages and the income drawn down each year in both nominal and net present value (NPV) terms.

An account-based pension drawn down only at the minimum rates can be expected to last beyond average life expectancy, although the NPV of the annual income will generally gradually diminish. In the below example, the net present value of the account balance at life expectancy is around 25 per cent of the initial opening account balance. The net present value of income from the pension declines steadily over time, but ‘ratcheting-up’ occurs when the regulated percentages increase, resulting in a somewhat variable income stream in nominal terms.

Chart 1

Note: The analysis assumes an average nominal investment return of 6 per cent. This is also the discount rate for net present value.

Note: The analysis assumes an average nominal investment return of 6 per cent. This is also the discount rate for net present value.

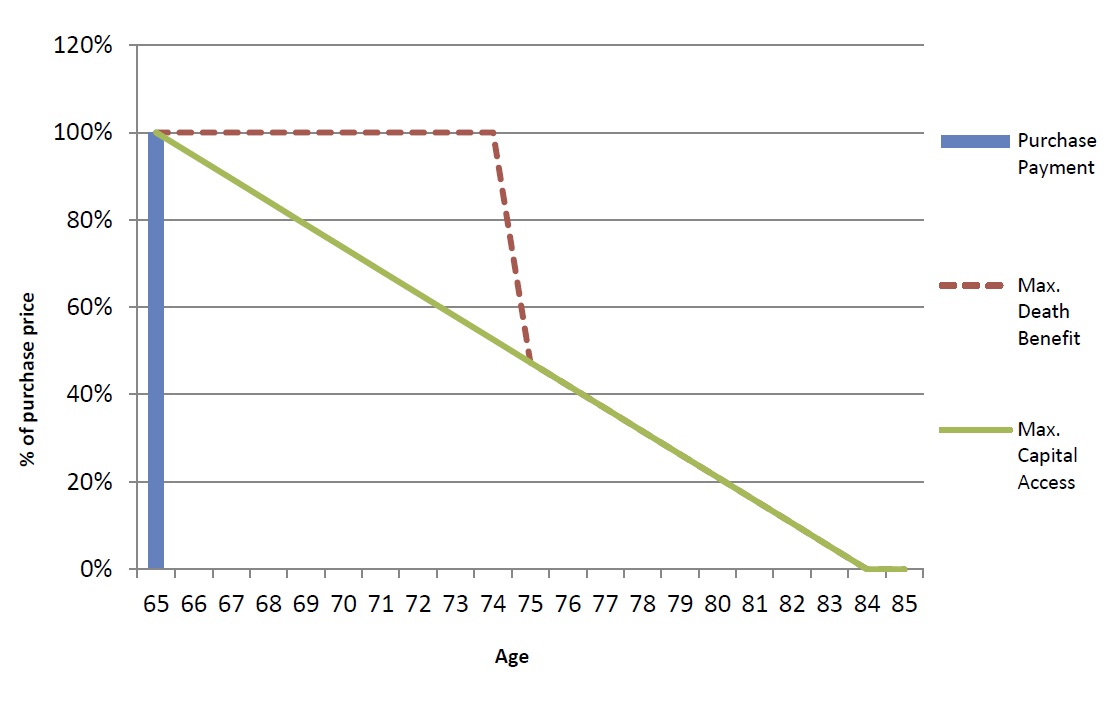

Proposed capital access schedule

Under the proposed alternative income stream rules, products would qualify for the earnings tax exemption provided the maximum amount that could be returned to the product holder if they withdraw from the product at a later date declines in a straight line from commencement to life expectancy.

In addition, products would be able to offer a death benefit of up to 100 per cent of the nominal purchase price for half of this period, with the maximum death benefit limited to the capital access schedule thereafter.

For example, male life expectancy at age 65 is approximately 19 years.

Under this proposal, a product sold to a 65 year old male could offer a declining commutation value such that the amount of the purchase price that could be returned on withdrawal would be zero by age 84, but a death benefit of 100 per cent could be offered for around 10 years (to age 75). Income payments would continue for life (see Chart 2).

In the case of deferred products, the schedule would commence at the same time as the product becomes eligible for the earnings tax exemption. For example, where an individual retires at age 65 and buys a deferred annuity that pays an income stream from age 80, the earnings tax exemption and the depreciation schedule would both commence from age 65, even though income payments would not commence until age 80.

Chart 2