The move for an inquiry into how banks treat small business customers should not overshadow the ongoing call for a broader royal commission on banks.

Several financial inquries (outlined below) have failed to tackle the growing concentration in the Australian finance sector, or the need to separate general banking from investment banking as the reform process in the United States, UK and Europe is contemplating.

Calls for a royal commission are also underpinned by ongoing reports of misconduct within the banks, summarised in a timeline of bad behaviour below.

Every other major industrial country is at an advanced stage in bank reform, and Australia would be isolated if it did not engage in a similar substantial and structural reform process.

Former Commonwealth Bank chief and Financial Services Inquiry Chair David Murray released the final report of the inquiry in December 2014. Britta Campion/AAP

Former Commonwealth Bank chief and Financial Services Inquiry Chair David Murray released the final report of the inquiry in December 2014. Britta Campion/AAP

Financial reform in Australia

1997 Wallis Inquiry

This inquiry has been associated with the “four pillars” policy towards bank mergers (though the inquiry itself did not propose this), and the opposition to any merger between ANZ, CBA, NAB and Westpac. The unwritten policy originated in Paul Keating’s reservations on concentration in the industry. It also led to the CLERP financial reforms announced on fund raising, disclosure, financial reporting and takeovers.

2009 Future of Financial Advice Inquiry

This inquiry stemmed from industry failures, such as Storm Financial and Opes Prime, and explored the role of financial advisers and the general regulatory environment for these products and services. It resulted in the Corporations Amendment (Future of Financial Advice) Act 2012 by the Labor government to tackle conflicts of interest within the financial planning industry. This was subsequently amended by the Liberal government in the Corporations Amendment (Financial Advice Measures) Act March 2016 which softened some of the reforms.

2012 Cooper Inquiry

This was a review into the governance, efficiency, structure and operation of Australia’s superannuation system. It examined measures to remove unnecessary costs and better safeguard retirement savings, claimed fees in superannuation were too high, and that choice of fund in superannuation had failed to deliver a competitive market that reduced costs.

2014 Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services Inquiry

This inquiry included proposals to lift the professional, ethical and education standards in the financial services industry. It aimed to clarify who could provide financial advice and to improve the qualifications and competence of financial advisers; including enhancing professional standards and ethics.

2015 Murray Inquiry

This inquiry was intended to provide “a ‘blueprint’ for the financial system over the next decade,” but fell somewhat short of this in not critically addressing the concentration or restructuring of the main banks. While acknowledging the high concentration and vertical integration of Australia’s banking industry the inquiry’s approach to encouraging competition was to seek to remove impediments to its development. The inquiry aimed to increase the resilience to failure with high bank capital ratios, and to reduce the costs of failure, including by ensuring authorised deposit-taking institutions maintained sufficient loss absorbing and recapitalisation capacity to allow effective resolution with limited risk to taxpayer funds.

Demonstraters throw their support behind US Senator Elizabeth Warren’s proposal to reform the Glass Steagall Act. Shannon Stapleton/Reuters

Demonstraters throw their support behind US Senator Elizabeth Warren’s proposal to reform the Glass Steagall Act. Shannon Stapleton/Reuters

In contrast to the limitations of the Australian reform process, more ambitious reform of the banking sector is being actively considered in the rest of the advanced economies. This is because of widespread international concerns regarding bank monitoring and standards, and the continuing threat of systemic risk and failure.

The objective is to create more effective competition, greater choice, improved governance, more balanced incentives, and responsible behaviour and performance. Central to international reform proposals is the intention of:

- shielding commercial banks from losses incurred by speculative investment banking

- preventing the use of public subsidies (eg central bank lending facilities and deposit guarantee schemes) from supporting risk taking

- reducing the complexity and scale of banking organisations

- making banks easier to manage and more transparent

- preventing aggressive investment bank risk cultures from infecting traditional banking;

- reducing the scope for conflicts of interest within banks

- reducing the risk of regulatory capture and taxpayers exposure to bank losses.

Among the ongoing international initiatives to reform the banks are the UK Banking Reform Act, which includes ring fencing retail utility banking from investment banking, due for implementation in 2019.

In the US, the 21st Century Glass Steagall Act, proposed by Elizabeth Warren and supported by Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton, involves separating traditional banks that offer savings and checking accounts from riskier financial services such as investment banking and insurance.

In Europe, the Liikanen Plan, announced in 2012, proposes investment banking activities of universal banks be placed in separate entities from the rest of the group. This has already been taken up widely throughout the European banking sector.

A licence to operate?

The banks have experienced continuous systemic risk (partly of their own making), erosion of their integrity, and a loss of public trust.

The Australian banks are on notice that they need to renew their licence to operate, to reconnect with their sense of duty and the Australian people, and to reconfirm their responsibilities to the Australian economy. This will occur, even if it takes a royal commission to achieve it.

A timeline of banks behaving badly

January 2004: NAB foreign currency options trading

NAB announces losses of A$360 million due to unauthorised foreign currency trading activities by four employees who concealed the losses. Bank risk policies and trading desk supervision prove ineffective. NAB sacks or forces the resignation of eight senior staff, disciplines or moves 17 others and restructures its board of directors. Four traders, including the head of the foreign currency options desk, are subsequently prosecuted and jailed.

2008: global financial crisis takes down Opes Prime, Storm Financial, Allco and Babcock and Brown

The market capitalisation of the stock markets of the world peaks at US$62 trillion at the end of 2007. By October 2008 the market is in free fall, having lost US$33 trillion dollars, over half of its value in 12 months of unrelenting financial and corporate failure. Originating in the toxic sub-prime securities of the New York investment banks, the financial crisis threatens to engulf the economies of the world.

The mythology today is that Australia miraculously escaped the global financial crisis due to the resilience of its regulatory system and the governance and risk management of its banks. The reality is that more than a dozen significant Australian companies went under during the crises (amounting to losses in excess of $60 billion in total). In almost every case at least one of the big four banks were involved in supporting the business models and extending credit to very doubtful enterprises.

July 2012: HSBC money laundering

A US Senate Inquiry discovers that HSBC allowed Latin American drug cartels to launder hundreds of millions of ill-gotten dollars through its US operations, rendering the dirty money usable. The HSBC Swiss private banking arm profited from doing business with arms dealers and bag men for third world dictators and other criminals.

HSBC agrees to pay a fine in excess of US$2 billion to settle US civil and criminal actions. In 2016 it is revealed that UK Chancellor George Osborne intervened to prevent criminal charges against HSBC as this might have undermined financial markets.

2013: Libor rigging

Libor is the international vehicle for settling inter-bank interest rates, and covers markets worth US$350 trillion.

In 2012 it’s revealed that wholesale fraudulent manipulation of the rates has been occurring for years, and throughout the reform process following the global financial crisis. The crisis engulfs many international banks including Barclays, Citigroup, Deutsche Bank and JP Morgan. The irony of the scandal is that Libor was intended as a measure of the state of health of the banking system.

The US Commodity Futures Trading Commission and US Department of Justice impose fines totalling hundreds of millions of dollars on the international banks. In Australia ASIC investigates the role of ANZ, BNP, UBS, and RBS and imposes fines. In 2014 the administration of Libor is transferred to the Euronext NYSE.

2014: Commonwealth Bank financial planning scandal

An ABC Four Corners report reveals CBA customers have lost hundreds of millions of dollars after the bank’s financial advisers recommend speculative investments.

The report describes the sales-driven culture inside the Commonwealth Bank’s financial planning division, with a focus on profit at all cost and a culture that has been built on commissions. The bank is found to have misled potentially thousands of clients.

The bank sets up an internal inquiry and compensation (though is subsequently accused of dragging its feet on compensation). A Senate inquiry into the performance of ASIC during the affair recommends establishing a Royal Commission to examine the banks.

May 2015: Forex manipulation

Following the Libor scandal, it is discovered that traders have been deliberately orchestrating trades in the $US5.3 trillion-per-day global foreign exchange market to their own advantage.

“They acted as partners – rather than competitors – in an effort to push the exchange rate in directions favourable to their banks but detrimental to many others,” says US Attorney-General Loretta Lynch. “And their actions inflated the banks’ profits while harming countless consumers, investors and institutions around the globe.”

US and British regulators fine Barclays, Citigroup, JP Morgan, RBS, UBS, and Bank of America more than US$6 billion in recognition of the scale and duration of the fraud.

March 2016: ASIC targets ANZ for rigging the bank bill swap rate (BBSW)

ASIC commences legal proceedings against ANZ for unconscionable conduct and market manipulation in relation to the bank’s involvement in setting the bank bill swap reference rate (BBSW) in the period March 2010 to May 2012. It foloows up with actions against NAB and Westpac.

The BBSW is the primary interest rate benchmark used in Australian financial markets, administered by the Australian Financial Markets Association (AFMA). It is alleged the banks traded in a manner intended to create an artificial price for bank bills.

March 2016: CommInsure payments scandal

The insurance arm of the Commonwealth Bank comes under media scrutiny for operating along similar lines to the earlier financial planning business.

A company whistleblower reveals the measures the bank is taking to avoid making insurance payouts to policyholders, many of whom are sick or dying.

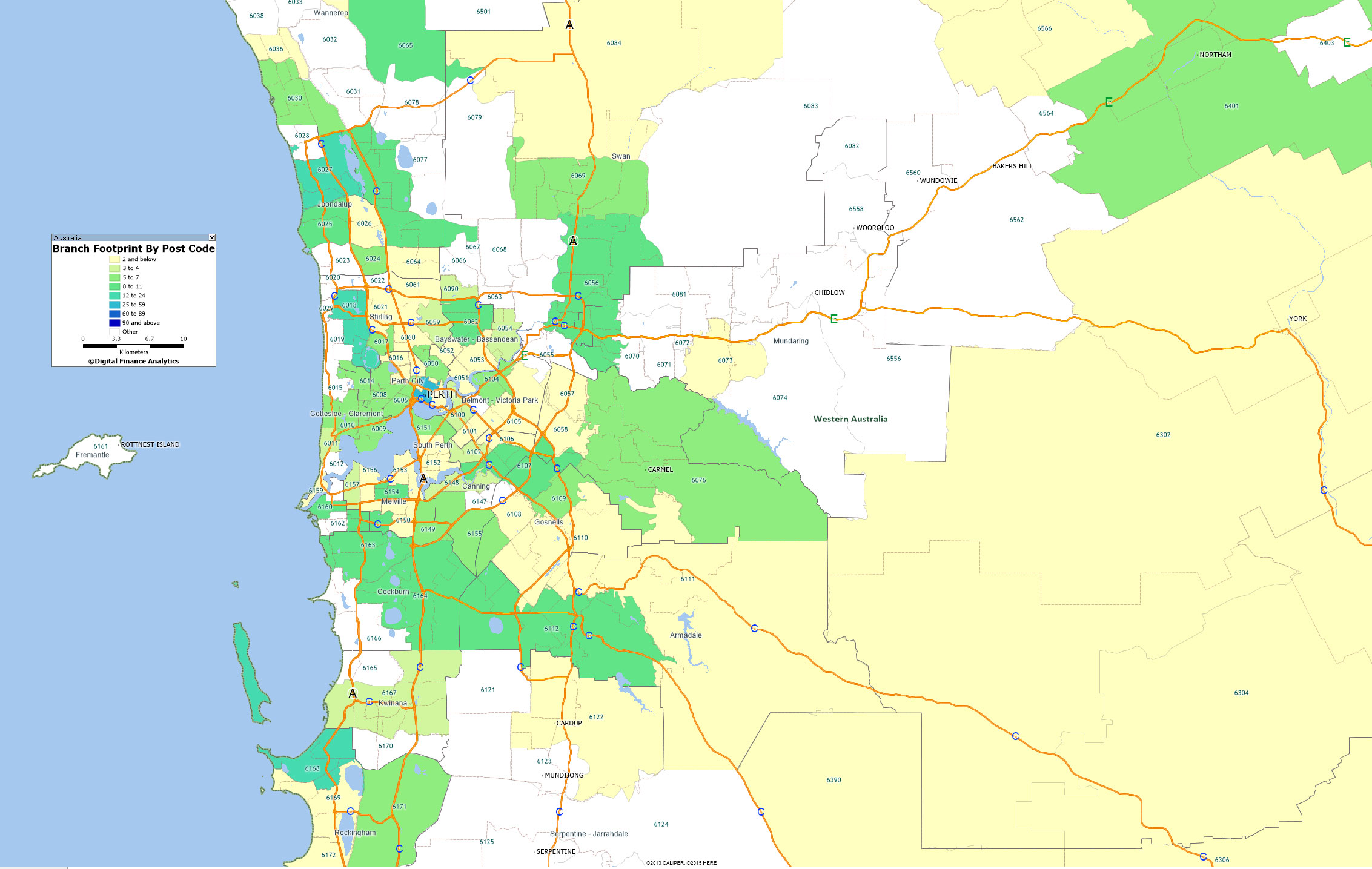

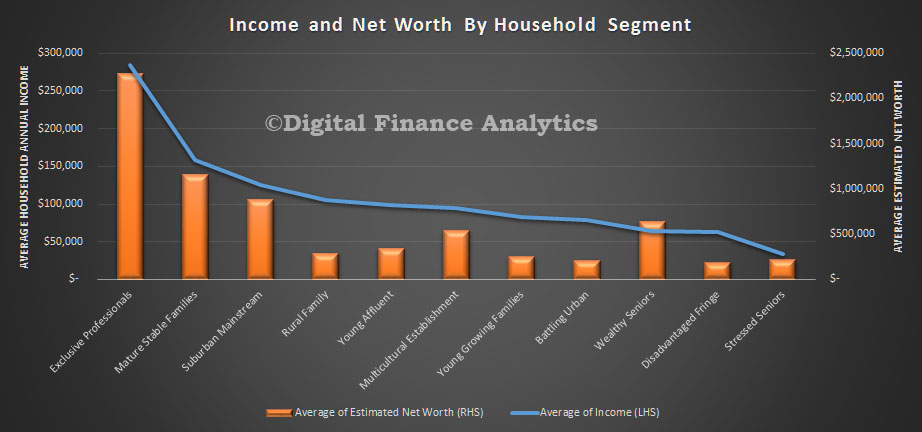

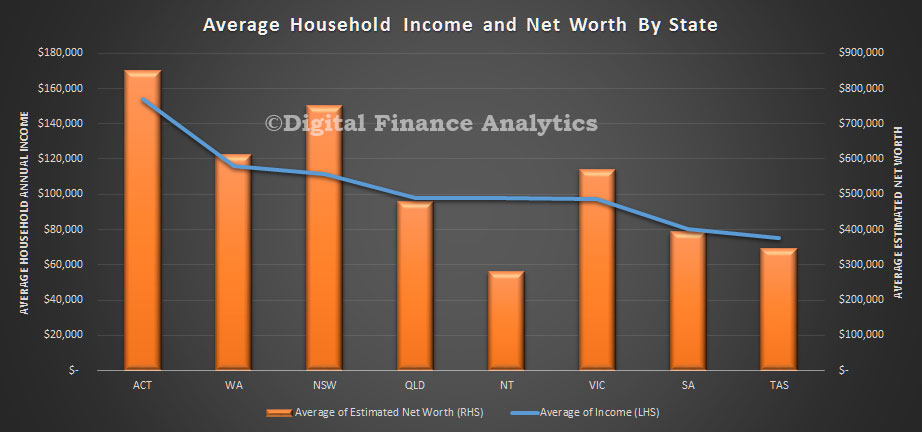

Next we show the relative household income and net worth by our master segments. The average household across Australia has an estimated annual income of $103,500 and an average net worth (assets less debts) of $600,600; the bulk of which is property related.

Next we show the relative household income and net worth by our master segments. The average household across Australia has an estimated annual income of $103,500 and an average net worth (assets less debts) of $600,600; the bulk of which is property related. There are wide variations across the segments. The most wealthy segment has an average annual income of more than eight times the least wealthy, and more than ten times the relative net worth.

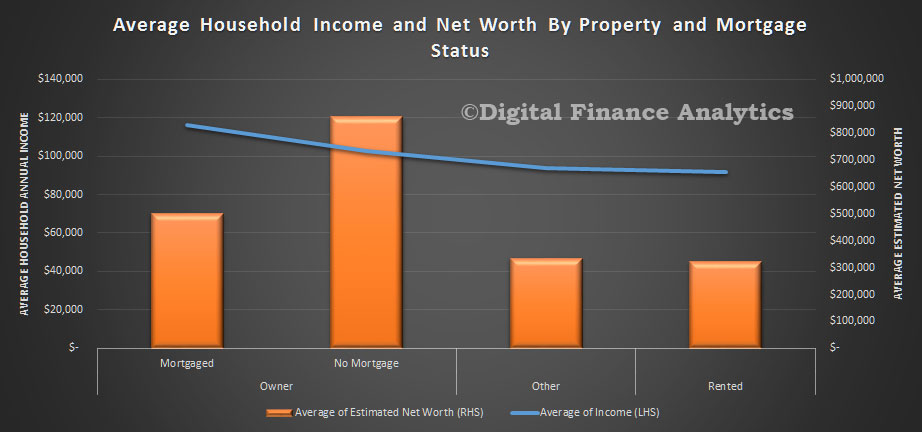

There are wide variations across the segments. The most wealthy segment has an average annual income of more than eight times the least wealthy, and more than ten times the relative net worth. Property owners are better placed, with significantly higher incomes and net worth, compared with those renting or in other living arrangements. Those with a mortgage have higher incomes, but lower net worth relative to those who own their property outright.

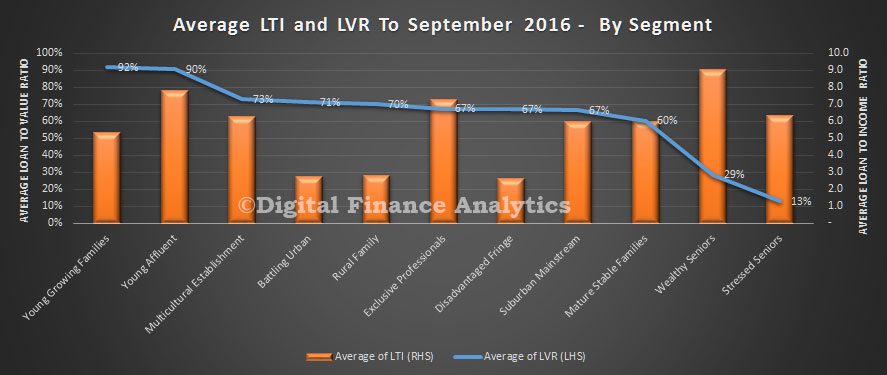

Property owners are better placed, with significantly higher incomes and net worth, compared with those renting or in other living arrangements. Those with a mortgage have higher incomes, but lower net worth relative to those who own their property outright. The loan to value (LVR) and loan to income (LTI) ratios vary by segment.

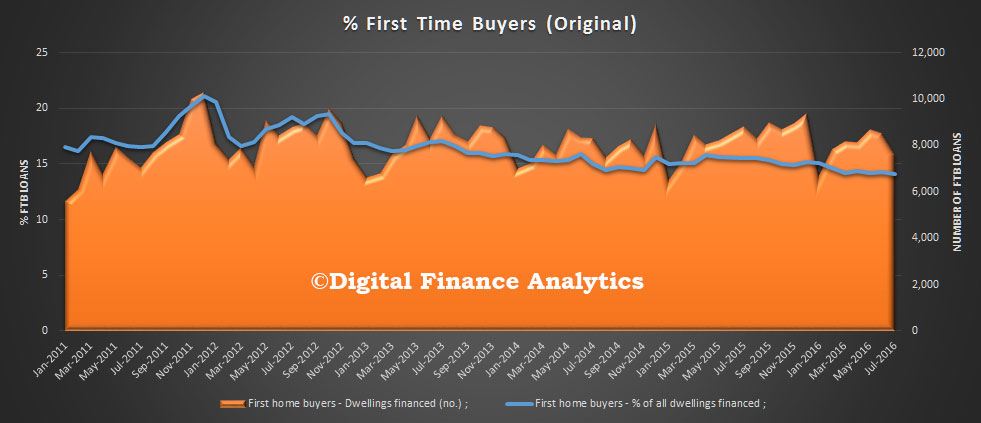

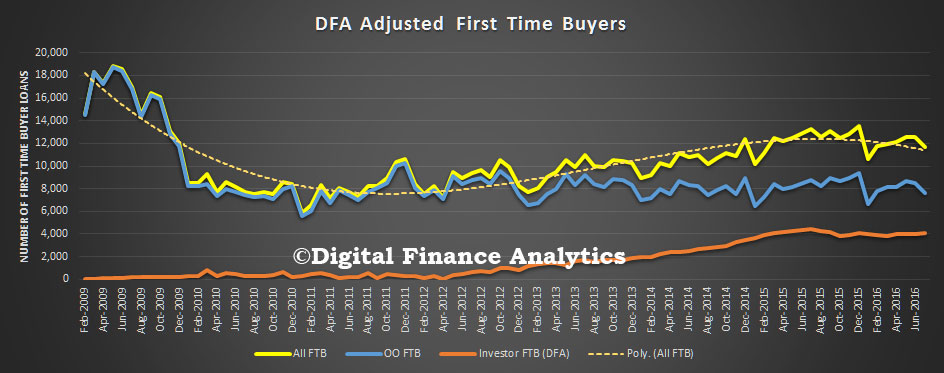

The loan to value (LVR) and loan to income (LTI) ratios vary by segment. Young growing families, many of whom are first time buyers, have the higher LVR’s whilst young affluent have the higher LTI’s (along with some older borrowers). Bearing in mind incomes are relatively static, those with higher LTI’s are more leveraged, and would be exposed if rates were to rise.

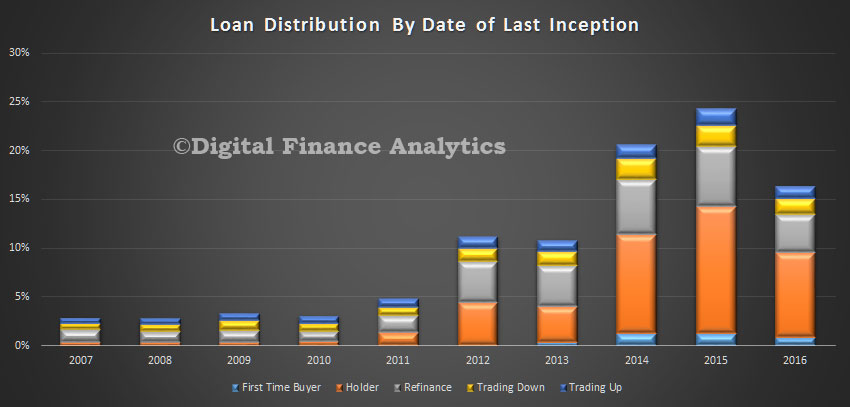

Young growing families, many of whom are first time buyers, have the higher LVR’s whilst young affluent have the higher LTI’s (along with some older borrowers). Bearing in mind incomes are relatively static, those with higher LTI’s are more leveraged, and would be exposed if rates were to rise. There is a relatively small proportion of much older dated loans which we have excluded from the chart above. Nearly a quarter of all loans churned in 2015, and 2016 shows the year to date count.

There is a relatively small proportion of much older dated loans which we have excluded from the chart above. Nearly a quarter of all loans churned in 2015, and 2016 shows the year to date count.