ASIC has evidently released the final scope of its review of remuneration in the mortgage broking industry – but only to industry insiders. According to media, the corporate regulator has confirmed it will review the remuneration arrangements of “all industry participants forming part of the value distribution chain”. This includes lending institutions, aggregation and broking entities, and associated mortgage businesses – such as comparison websites and market based lending websites – and referral and introducer businesses.

But why, we ask, was the scope not publicly disclosed? Why are ASIC seeking input only from industry participants? We agree the remuneration review is required – but the lack of transparency is a disgrace.

We asked ASIC about this and they replied:

At this point in time, ASIC has not published a media release commenting on the review or making the review available for download at this stage.

ASIC will usually put out a public statement, such as a media release or media advisory, on significant regulatory activities and outcomes, in order to:

- be transparent and accountable for what we do

- help inform our regulated population and the public of expected standards and of our priorities and areas of focus.

So they are happy with a private review evidently!

Worth also bearing in mind, the UK banned commission payments in the mortgage industry, which has moved to a fee for service model.

ASIC has released the final scope of its review into the mortgage broking industry, in which it confirms the review will extend far beyond mortgage brokers.

The final scope, released to the industry yesterday, sets out the parameters of the review. These were informed by input received from industry and consumer representatives through industry roundtables and subsequent written feedback. In it, the corporate regulator has confirmed it will review the remuneration arrangements of “all industry participants forming part of the value distribution chain”.

This includes lending institutions, aggregation and broking entities, and associated mortgage businesses – such as comparison websites and market based lending websites – and referral and introducer businesses.

ASIC also confirmed the review will extend to non-monetary benefits that relate to the distribution of residential loan products.

However, the review will not extend to loan products outside of residential mortgages, such as reverse mortgages or construction loans, which do not comprise a predominate proportion of the home lending mortgage market.

NAB has already come out in support of ASIC’s final scope.

“We believe ASIC’s scope is appropriate and we look forward to continuing to work with the regulator throughout the review,” Anthony Waldron, NAB EGM broker partnerships, said.

“We’re dedicated to working with brokers to deliver a great customer experience and we believe this review will help continue to build trust and confidence in the mortgage broking industry.”

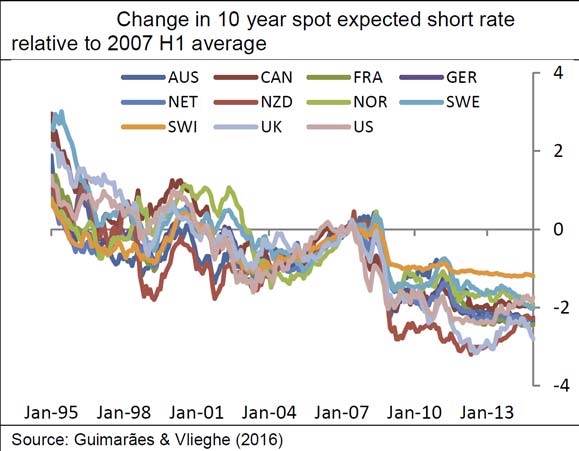

In a speech to the London Business School

In a speech to the London Business School