There could be troubled times ahead for small businesses and contractors working in construction, with property analysts and economists kicking of the year with predictions the residential apartment sector slowdown could cause pain.

“There is absolutely no question we have seen a considerable softening in the construction end of the residential apartment space,” Watpac managing director Martin Monro warned in The Australian today.

While data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics shows new housing starts in the year to September rebounded, experts and industry leaders have been divided in commentary on the state of the sector and what the next 12 months will hold for builders and their suppliers.

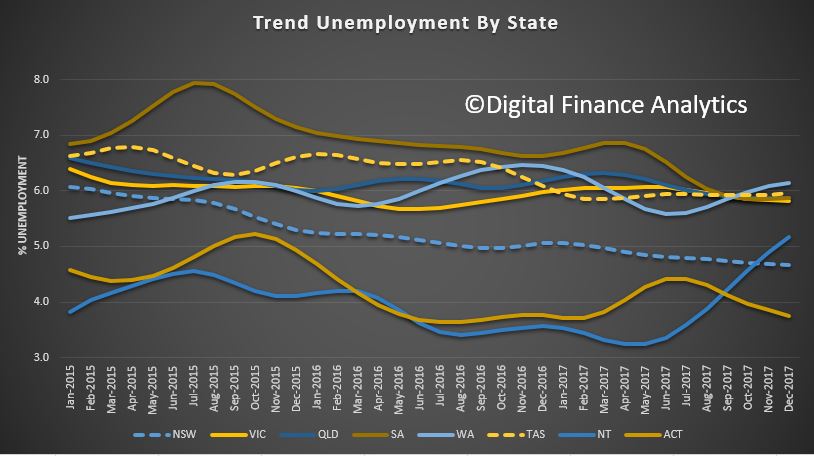

Digital Finance Analytics principal Martin North says while it’s not a uniform trend across the country, there are troubling signs on the eastern seaboard in particular.

“What I’m noticing is that those in the construction sector – from small builders to sub-contractors – have significantly lower confidence levels than they did six months ago,” he says.

“Their forward pipeline of work is wilting, especially across Brisbane and Melbourne. And now I’m seeing it in and around Sydney for the first time.”

And it’s demand for high rise apartments, he says, that is seeing the biggest drop.

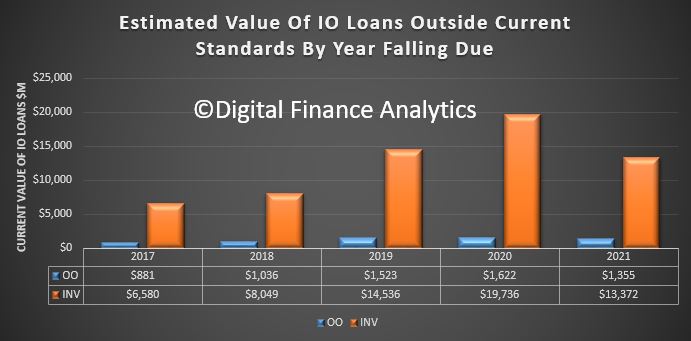

“Investors are quite concerned because capital values look to have stalled and could be reversing. It’s also much more difficult to get financing now and foreign buyers have defected,” he says.

North says there could be more pain to come in Queensland.

“Brisbane is where the pain is most extreme, but I’m seeing it in and around Melbourne and Sydney now.”

Sub-contractors concerned over risks of non-payment

Weakness in the Brisbane market has already claimed its casualties, with several builders having liquidated in the last year.

Among the 2017 collapses was Queensland One Homes back in August and CMF Projects in June.

With several other builders having suffered a similar fate, there are fears any continued slowdown could see more sub-contractors not getting paid. Those working as contractors in the building space are worried more pain could be to come this year.

“The industry is a shambles and is overseen by an inept QBCC who are hamstrung by poor legislation,” says Subbie United’s John Goddard.

Goddard claims sub-contractors have a difficult time recovering what they owe in the event a building company collapses.

“You then have pre-insolvency advisors telling these builders how to hide assets before they recommend a friendly liquidator to defeat creditors who are in the main, subbies.”

Housing a cyclical industry

However, small business ombudsman Kate Carnell says while weakness exists in some parts of the building sector, small businesses and contractors should not be alarmed.

“The thing about the industry is it’s cyclical. There’s big ups and downs and that’s how it works. And in some places there’s an oversupply in that space,” she says.

“But if you look at some of the figures around new home starts, there’re looking pretty good and strong. There’s still a dearth of new homes in the markets as we’ve got quite strong population growth.”