Our friends at Mozo have written a highly relevant blog post for DFA on the impact of the APRA changes. No wonder, some households are under pressure! And thanks to Mozo for their insights!

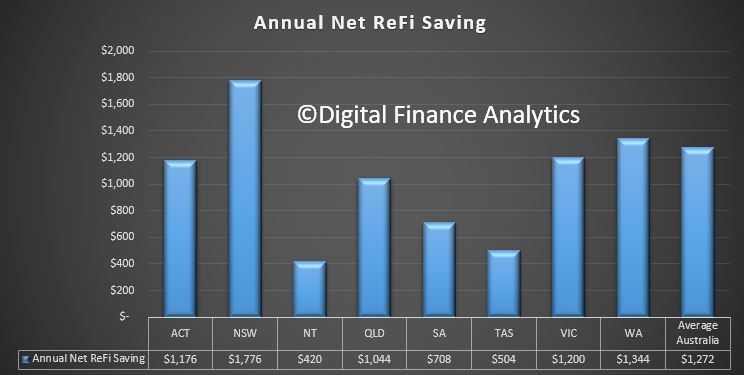

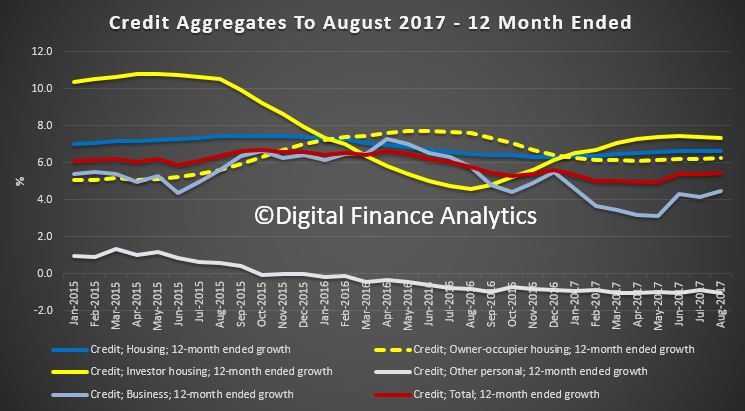

There’s been a reasonable amount of ups and downs in home loan interest rates over the last 12 months, especially considering the official cash rate hasn’t changed since August last year. Many of those changes served to draw clear lines between borrower and repayments types, as banks aim to cut back on risky lending after APRA updated regulations earlier in the year. The changes included a 30% cap on new interest-only lending and a mandate for stricter limits on interest-only loans with LVRs above 80%.

And the different interest rate changes between borrowers types have been pretty dramatic. While at one end of the scale, owner-occupiers making principal and interest repayments saw hardly any change, on the other, riskier, end, investors with an interest-only loan – who perhaps saw the biggest changes thanks to APRA’s updated rules – have been hit by the equivalent of more than two typical RBA rate hikes.

Here’s a full breakdown of the movement in different rate types over the 12 months from October 2016 to today.

Owner occupiers making principal and interest repayments – 0.01% increase

People buying their own home and paying off the principal and interest each month have fared the best over the past year, with an increase of just 0.01%, bringing the average rate to just 4.03%.

That’s good news, since according to analysis done by ASIC, the majority of owner occupiers fall into this category. Even better news is that the lowest rate around at the moment for this borrower group is 3.54% – 0.10% higher than it was in October 2016, but still a very competitive offer.

This very minimal rate change over a 12 month period in part reflects the fact that this group is the least risky from a bank’s perspective. Unlike other rate types, there was a pretty even split between the number of lenders who increased rates (30) and those who decreased (33).

Owner occupiers making interest only repayments – 0.25% increase

According to ASIC, one in four owner occupiers have an interest only loan. Unlike loans with principal and interest repayments, in this category there was an undeniable trend toward rate increases, with 40 lenders raising rates, while just 5 lowered them over the 12 month period from October 2016. This points to the extra risk interest only repayments pose for banks.

Borrowers in this category have been hit by an average rate increase of 0.25%, equal to a typical RBA rate hike. The average interest rate went from 4.15% in October 2016, to 4.40% today.

On a $500,000 home loan that change equates to $1,250 of extra interest per year.

Investors making principal and interest repayments – 0.27% increase

Investors are often hit harder by rate increases, and with APRA regulations tightening around new lending to ‘riskier’ borrower types, this year has been no different.

Rates rises for investors making principal and interest repayments were more or less on par with owner occupiers on an interest only loan, with an increase of 0.27%, to 4.61%. That change meant an extra $1,350 in interest over a year long period for those is this rate category.

This is a bit more than the equivalent of a Reserve Bank rate rise, reflecting the level of risk lenders see in investment lending. Again, there was a trend toward increases by lenders (53) rather than decreases (8).

Investors making interest only repayments – 0.53% increase

Where investors making principal and interest repayments saw a little over the equivalent of one typical RBA rate rise in the last 12 months, rates for interest only investor loans went up by an average of 0.53% – or more than two times an RBA rate rise.

There was an overwhelming trend towards lenders increasing instead of decreasing rates in this category as well, with just 1 lowering rates, while 45 hiked.

That brought the average rate from 4.39% in 2016 to 4.92% this year, a change that meant a whopping $2,650 of extra interest paid on average. Not only is this rate increase bigger than that for other borrower types by a pretty large margin, but it also likely affected more people, considering ASIC data found two in three investment borrowers have an interest only loan.

What this means

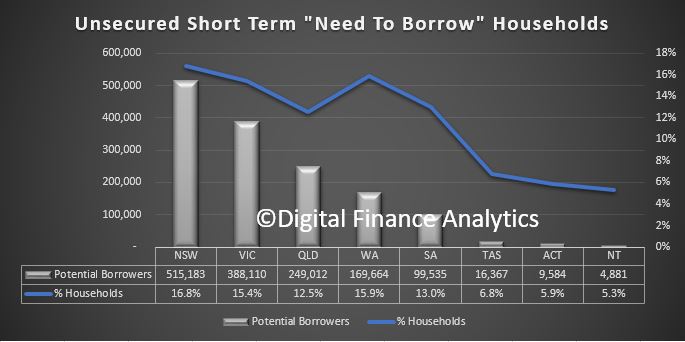

While the banks have the prerogative to protect themselves against riskier lending by imposing higher premiums, overall I’d argue that the rate changes over the past year have potentially had a negative effect on the wider economy.

Most borrower categories saw rate increases equivalent to one or more Reserve Bank hikes, which can have a significant impact on household budgets – and the economy overall. As more money goes toward home loan repayments and borrowers brace for more rate hikes to come, consumer confidence drops, and the economy starts to stall.

And that’s bad news for everyone, risky home loan or not.

About the Author: After starting his career working for the banks, Peter Marshall has spent the last 15 years helping consumers compare financial products. At Mozo he manages the Data Team which keeps track of banking, insurance and energy products in Australia.