Their submission focuses on APRA’s role in the financial system, potential indicators of competitive dynamics within the industries APRA supervises and its approach to balancing the objectives of financial safety and stability with considerations of competition and competitive neutrality.

A strong prudential framework contributes to strong financial entities and these, in turn, help create robust competitors and intermediaries that are able to support economic growth and activity, throughout the economic cycle.

Most industry sectors regulated by APRA display relatively high levels of concentration, with a small number of large entities holding a significant combined share of the market. However, industry concentration may not, of itself, be a comprehensive measure of the level of competition in individual markets for financial services products. There appear to be strong indicators of competition in certain financial services product markets, for example residential mortgages.

APRA recognises that its objectives are interlinked, with a strong and stable financial system delivering significant efficiency benefits and the promotion of a competitive financial sector. The efficiency and competition benefits of a stable financial system are not limited to the financial sector but extend to the broader Australian economy.

APRA is of the view that, with the right balance, stability and competition are mutually reinforcing objectives. However, competition can also lead to instability in the financial system and there are times where it is important for APRA to actively temper competitive forces. Periods of excessive and unsustainable competition can result in financial institutions inappropriately pricing risk or unintentionally accepting excessive risk in order to gain or retain market share.

Turning to their specific observations on the banks, they say there has been no material growth in the combined market share of the major banks over recent years. The share of the four major banks as at end-June 2017 was 75.2 per cent, compared with 75.8 per cent as at end-June 2016. Five years ago, the corresponding figure was 74.5 per cent.

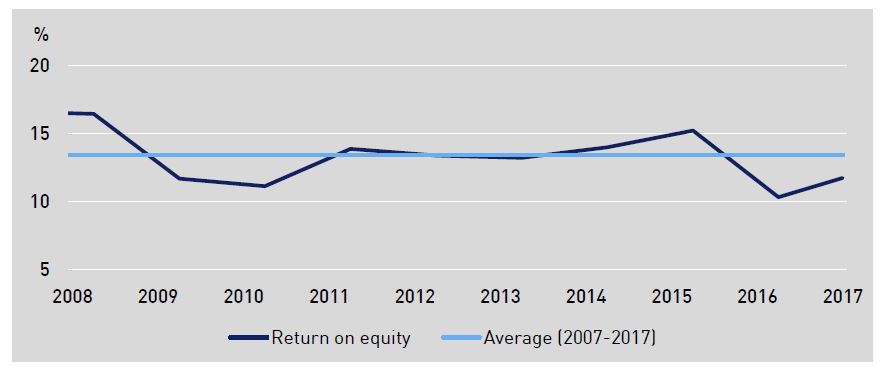

Return on equity (ROE) for the banking industry for the twelve months to 30 June 2017 was 11.7 per cent. This remains below the ten-year average of 13.4 per cent (which itself has declined in recent years) and is primarily driven by net interest margins, which continue to be challenged by the low interest rate environment. Margin pressure has eased following recent mortgage repricing actions (particularly on investor and interest only products); however, rising funding costs and slowing credit growth may offset much of the benefit afforded by upwards repricing. All else being equal, increasing regulatory capital expectations will also likely negatively impact industry ROE.

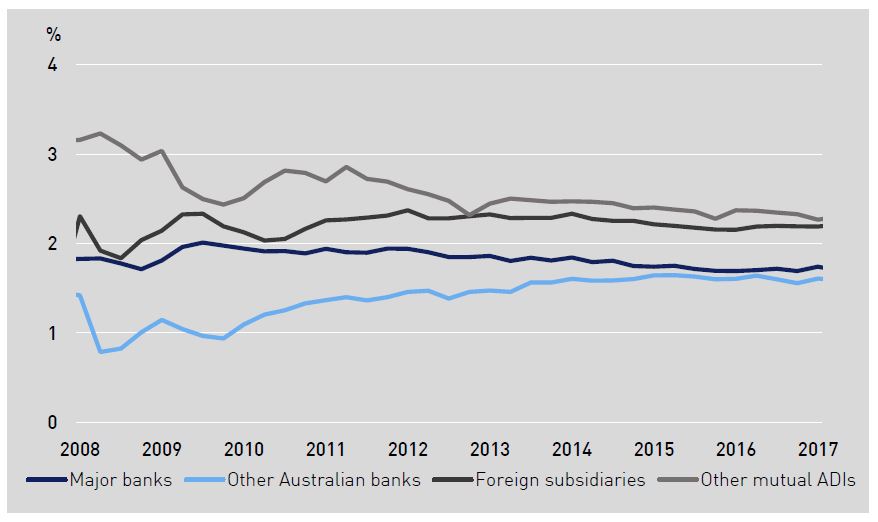

Since the global financial crisis there has been a significant convergence in ADI net interest margins. The net interest margins of other Australian banks (including the large regional banks) as shown in Figure 5 have increased over the past ten years, from 0.8 per cent at June 2008 to 1.6 per cent at June 2017, partly driven by wholesale funding being replaced with cheaper funding as volatility in funding markets has eased. Conversely, the net interest margins of other mutual ADIs have been compressed over the same period, falling from 3.2 per cent at June 2008 to 2.3 per cent at June 2017, driven by a combination of pricing competition in both lending and retail deposit markets

Expense management and efficiency continue to be a focus as both large and small ADIs seek to become more competitive and profitable. Cost to income ratios for the majority of ADIs continue to trend downward. The cost to income ratios of large banks compare favourably to those of peers in foreign jurisdictions.

Large banks are likely to have a strong competitive and information advantage in supplying lending products to these businesses through their ability to cross sell or bundle other banking products, particularly payment systems/merchant terminals and transaction accounts. For many smaller ADIs, offering finance to small and medium enterprises would potentially result in the ADI operating outside tolerance levels established by their own risk appetite. However, as an alternative to accessing funding from the larger banks, small businesses may also access trade credit or asset/equipment finance from specialist companies that are not regulated by APRA to fund their establishment or expansion.

Four observations. First, they should have compared returns and NIM on an international basis. Australian banks are super profitable relative to players in many other countries thanks to weaker competition and the market moving rates together (see the recent mortgage repricing).

Second, we may have better cost income ratios here, but that has more to do with income from superior profits than core efficiency. The cost-income metrics are meaningless in isolation.

Third, the current regulatory and competitive settings still create a significantly tilted playing field in favour of the big four, and the barriers to new entrants are too high.

Fourth, we have strong vertical and cross product integrated (e.g. wealth management, retail banking); financial advice, mortgage brokers, as well as product manufacturing. This tight integration allows players to control prices and margins. This is a structural problem, which no-one wants to address.

We think APRA have traded off competition in favour of financial stability, which is their primary concern. But as a result consumers and small business customers are paying more than they should for financial service products, which is effectively a tax on all Australians.