Markets are beginning to ask whether companies will be capable of passing on higher costs to the U.S.’ less than financially robust middle class, according to Moodys.

The U.S.’ still relatively low personal savings rate questions how easily consumers will absorb recent and any forthcoming price hikes. Moreover, the recent slide by Moody’s industrial metals price index amid dollar exchange rate weakness hints of a leveling off of global business activity.

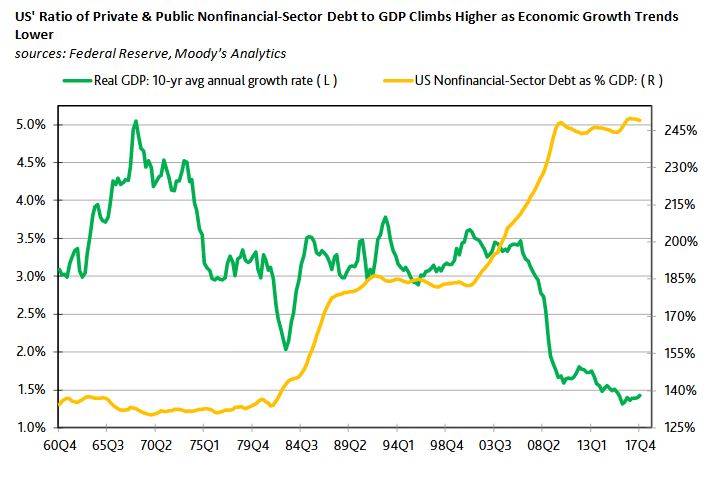

Missing from last week’s discussion of a record ratio of U.S. nonfinancial-corporate debt to GDP was any mention of 2017’s near-record high ratio of total U.S. private and public nonfinancial-sector debt relative to GDP. The yearlong averages of 2017 showed $49.05 trillion of total nonfinancial-sector debt and $19.74 trillion of nominal GDP that put nonfinancial-sector debt at 249% of GDP—or just a tad under 2016’s record 250%.

The leveraging up of the U.S. economy has coincided with a downshifting of U.S. economic growth. From 1961 through 1979, U.S. real GDP expanded by an astounding 3.9% annually, on average, while total nonfinancial-sector debt approximated 133% of nominal GDP. When real GDP’s average annual rate of growth eased to the 3.2% of 1979-2000, the ratio of nonfinancial-sector debt to GDP rose to 176%. Since the end of 2000, U.S. economic growth has averaged only 1.8% annually and, in a possible response to subpar growth, nonfinancial-sector debt has soared to 232% of GDP

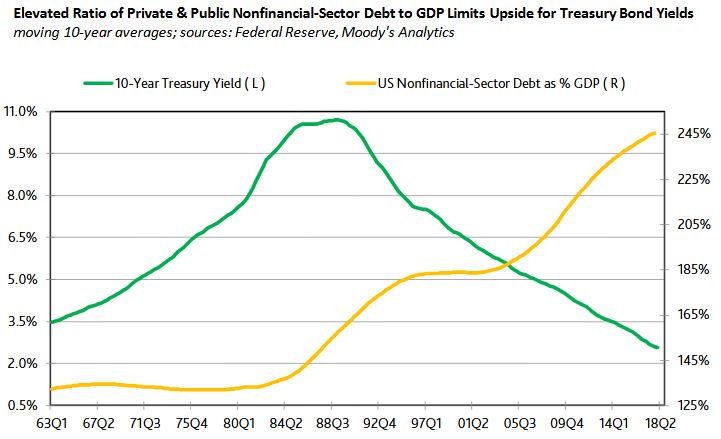

High Systemic Leverage Reins in Benchmark Yields

Over time, the record shows that the climb by the moving 10-year ratio of nonfinancial-sector debt to GDP has been accompanied by a declining 10-year moving average for the 10-year Treasury yield. For example, as the moving 10-year ratio of debt to GDP rose from 1997’s 183% to 2017’s 245%, the 10-year Treasury yield’s moving 10-year average fell from 7.31% to 2.59%.

Two factors may be at work. First, lower interest rates encourage an increase in balance-sheet leverage. Second, to the degree an elevated ratio of debt to GDP heightens the economy’s sensitivity to an increase in interest rates, lofty readings for leverage limit the upside for interest rates. Moreover, as shown by the historical record, if higher leverage tends to occur amid a slower underlying pace of economic growth, then the case favoring relatively low interest rates amid high leverage is strengthened.

None of this dismisses the possibility of an extended stay above 3% by the 10-year Treasury yield. Instead, today’s record ratio of debt to GDP warns of greater downside risk for business activity whenever interest rates enter into a protracted climb.