The Government view is high home prices is ultimately driven by lack of supply, relative to demand, including from migration. So the solution is to build more (flick pass to the States!). It has nothing to do with excessive debt, nor does the fact the average number of people per home is falling signify anything. And tax policy is not the problem.

However, a new working paper “Regional housing supply and demand

in Australia” from the ANU Center for Social Research and Methods blows a mighty hole in that mantra. They suggest that demand factors (availability of loans, tax concessions etc.) have a significant impact, while demand and supply equilibrium varies significantly across different regions, with some hot spots, and some where vacant property exists (yet prices remain high, because of these demand factors). Significantly, much of the surplus is in areas where high-rise development has been strong. We think this may signal further downward pressure on prices in these areas.

Over the year to June 2017 Australia built nearly 220,000 dwellings. Construction rates of units and other attached housing have more than doubled this decade, with around 103,000 units, townhouses and terrace houses completed in the latest financial year. Most of these completions are high-rise units in Australia’s capital cities (which is why the average home size is falling). Detached house completions have also trended up in recent years, but the growth has been more modest. This paper accounts for differential in the type of stock being built, with detached housing supporting a greater number of persons per dwelling than units and townhouses.

Over the year to June 2017 Australia built nearly 220,000 dwellings. Construction rates of units and other attached housing have more than doubled this decade, with around 103,000 units, townhouses and terrace houses completed in the latest financial year. Most of these completions are high-rise units in Australia’s capital cities (which is why the average home size is falling). Detached house completions have also trended up in recent years, but the growth has been more modest. This paper accounts for differential in the type of stock being built, with detached housing supporting a greater number of persons per dwelling than units and townhouses.

The paper measures the gap between housing supply and demand at

a regional level in Australia. They have taken into account a range of complicating factors such as changing demographics, building types and the increase in unoccupied dwellings at the regional level.

Previous research efforts in Australia focus on national estimates of the housing ‘gap’ or shortage but here we recognise that housing markets tend to be regional and that house price movements and affordability are likely to be as influenced by local demand and supply conditions as by broad national conditions.

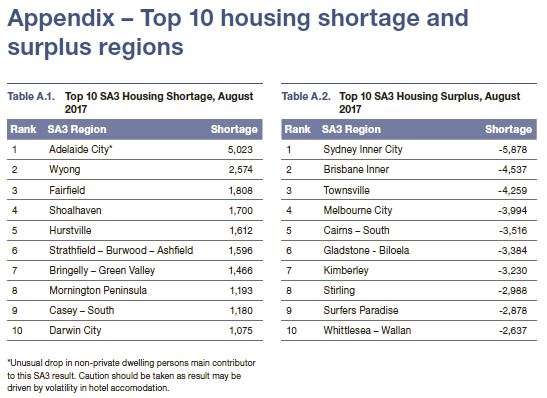

Between the years 2001 and 2017, we estimate the Australian housing market experienced an oversupply of 164,000 dwellings. However, there are significant regional differences with some regions experiencing significant undersupply while others have significant housing surpluses.

Nationally, we do find periods of significant undersuppy, particularly between 2007 and 2014 but for other periods beyond 2001 we find oversupply more than compensated.

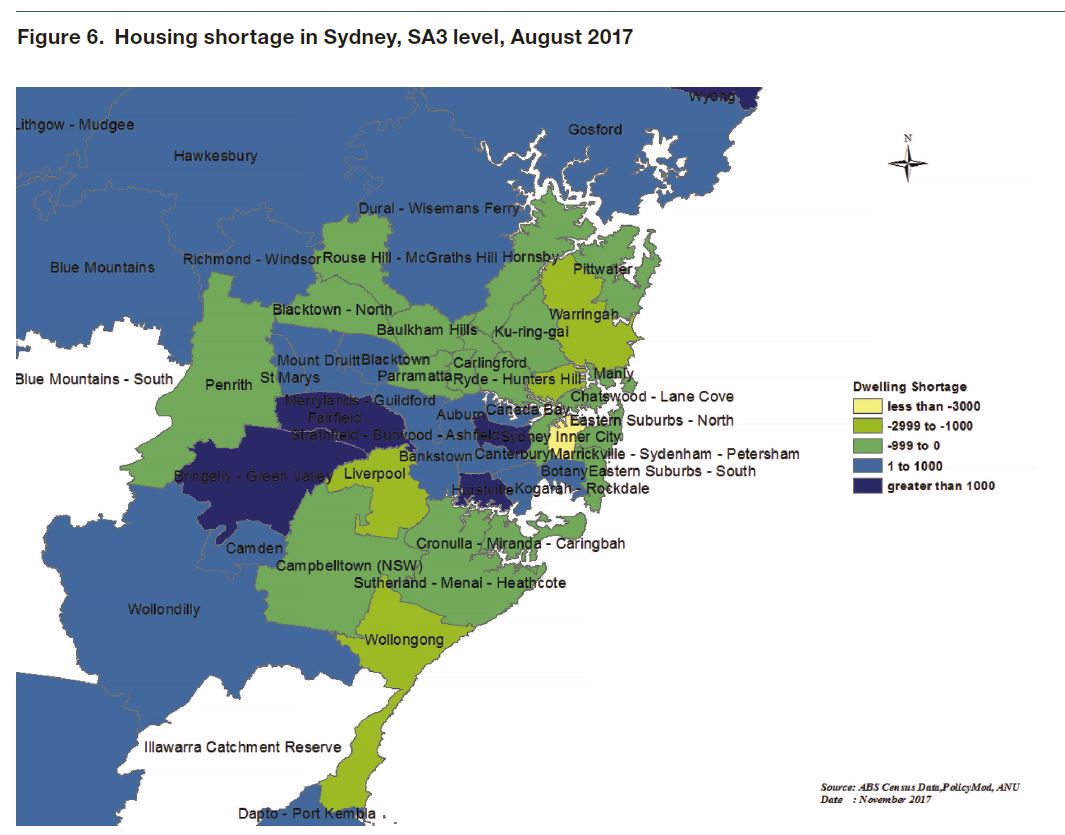

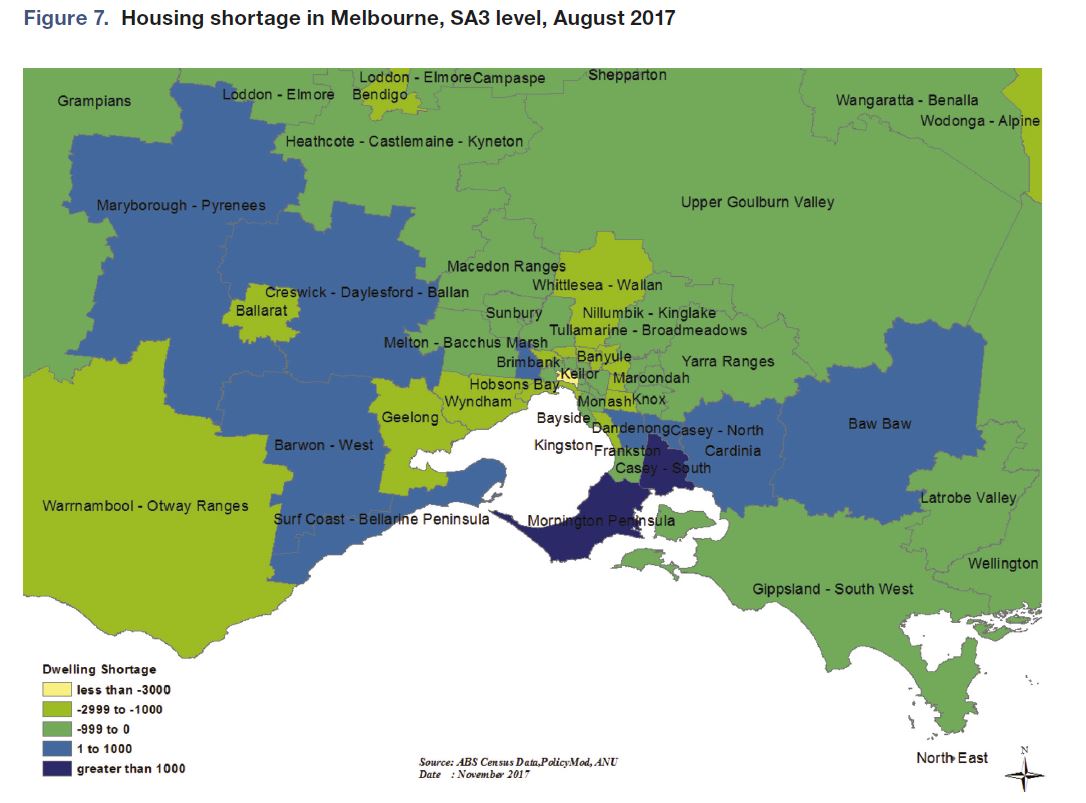

The majority of Australia’s housing surplus is situated in the inner-city areas of its major capitals, with Inner Brisbane, Melbourne and Sydney all oversupplied due to recent strong growth in unit developments. Many regional centres, particularly those in mining-sensitive areas such as North

Queensland and Western Australia, also retain housing surpluses.Many regions in the middle and outer rings of our major capital cities, particularly Sydney, face modest housing shortages.

The modelling suggests that there is some evidence, albeit relatively weak, that a housing shortage is associated with higher house price growth.

The analysis exclusively concerns the concept of underlying demand, recognising that this may not be representative of the demand for housing in a traditional economics sense. The paper also acknowledges the limitations of the analysis in terms of both its conceptual basis and the data it relies on.

This paper does not conclude that people’s housing needs are being met or that what is being supplied is at an affordable price point for all families.

The lack of a housing shortage may have significant implications for housing policy in Australia and the economy more broadly. If Australia’s current record home-building levels are not balanced by a large housing shortage, then there is the risk that these current levels will reduce in the near future. Policy makers will also need to place greater emphasis on other potential drivers of house price growth and housing affordability, such as a range of demand influences.