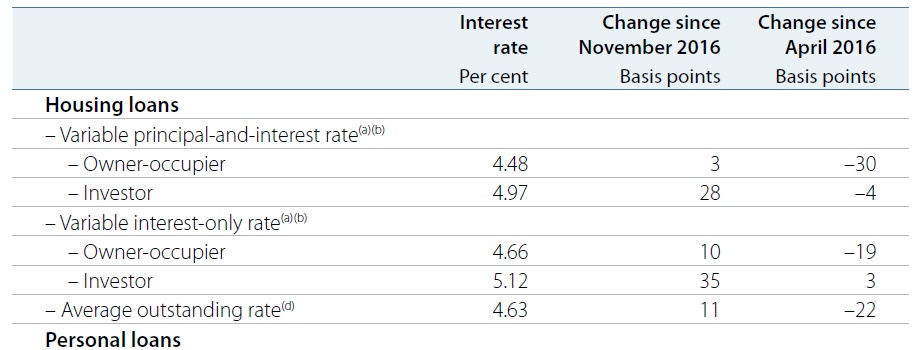

The latest RBA Quarterly Statement on Monetary Policy says low wages growth will cramp growth, and also includes information on household finances and mortgage lending. They say that interest only investors have seen an average rise of 35 basis points since Nov 2016, and a principal and interest investor of 28 basis points. Personal loan rates have also risen by 25 basis points since April 2016 (despite cash rate cuts). Major banks have a lower share of the home loan market as more business to the non-banks and other lenders.

Housing credit growth was stable in recent months at an annualised rate of around 6½ per cent. Growth in credit extended to investors has steadied at an annualised pace of around 8 per cent, after accelerating through the second half of 2016. This stabilisation in investor credit growth is consistent with the slight reduction in investor loan approvals and may have been partly driven by the increases in interest rates for investors in late 2016 along with further tightening in lending standards by lenders around that time.

The decline in loan approvals in recent months has been driven by a decline in approvals in Victoria, while loan approvals in New South Wales have remained near record highs (Graph 4.11).

Housing finance for new dwellings has been little changed recently following rapid growth through 2016; housing finance for the construction of new homes has remained stable (Graph 4.12). Overall, loans for new dwellings or dwellings under construction are estimated to have contributed more than half of credit growth over the past year. This contribution is expected to rise, based on the pipeline of residential construction work under way.

The major banks’ share of housing loan approvals has fallen in recent months to its lowest level since 2008. Most of this reduction appears to have been absorbed by other Australian and foreign banks (Graph 4.13). Housing credit issued by entities that are not licensed by APRA as authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) is estimated to have increased slightly in recent quarters, but at around 3 per cent remains a very small share of housing credit.

The further increases in housing interest rates announced by some lenders in March and April and prudential guidance from APRA and ASIC regarding interest-only lending can be expected to affect housing credit growth over the months ahead.

As outlined in the April Financial Stability Review, the Council of Financial Regulators (CFR) has been monitoring and evaluating the risks to household balance sheets. APRA announced further measures in March 2017 to reinforce sound housing lending practices. ADIs will be expected to limit new interest-only lending to 30 per cent of total new residential mortgage lending and, within that, to tightly manage new interest‑only loans extended at loan-to-value ratios above 80 per cent. APRA also reinforced the importance of banks: managing their lending so as to comfortably meet the existing investor credit growth benchmark of 10 per cent; using appropriate loan serviceability assessments, including the size of net income buffers; and continuing to exercise restraint on lending growth in higher risk segments. APRA also announced that it would monitor the growth in warehouse facilities provided by ADIs. These facilities are used by non-bank mortgage originators for short-term funding of loans until they are securitised.

In addition, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) announced in April further steps to ensure that interest‑only loans are appropriate for borrowers’ circumstances and that remediation can be provided to borrowers who suffer financial distress as a consequence of shortcomings in past lending practices.

Since February, the major banks have announced an average cumulative increase to their standard variable rates of around 25 basis points for investors and a few basis points for owner‑occupiers. Also, borrowers will pay an additional premium for interest-only loans of around 15 basis points for investors and 20 basis points for owner-occupiers (Graph 4.14).

The rates actually paid on new variable rate loans are likely to differ from the major banks’ standard variable rates. The major banks and other lenders offer discounts to their standard variable rates, which can vary through time particularly for new borrowers; for example, in 2015, increases in interest rates on existing borrowers were reportedly accompanied by larger unadvertised discounts for new borrowers.

Overall, the increases that have been announced to date by lenders are expected to raise the average variable rate paid on outstanding housing loans by around 15 basis points. The average outstanding rate on all housing loans is expected to increase by slightly less than the variable rate since interest rates on new fixed-rate loans remain below those on outstanding fixed-rate loans.

As has been the case for some time, there is considerable uncertainty around the timing and extent to which domestic cost pressures will rise over the next few years. As wages are the largest component of business costs, the outlook for wage growth is particularly important for the inflation outlook. The recovery in wage growth could be stronger than anticipated if conditions in the labour market tighten by more than assumed, or if employees demand wage increases to compensate for the sustained period of low real wage growth. However, it could be the case that some of the factors currently weighing on wage growth, such as underemployment in the labour market or structural forces such as technological change, are more persistent or pervasive than assumed.

The path of inflation will also depend on whether the heightened competitive pressures in the retail sector continue to constrain inflation. On the other hand, the earlier increases in global commodity prices and increases in domestic utilities prices could flow through to domestic inflation (through higher business costs) by more than assumed.

Another factor affecting the outlook for CPI inflation is that the weight assigned to each expenditure class in the CPI will be updated in the December quarter 2017 CPI release. Measured CPI inflation is known to be upwardly biased because the weight assigned to each expenditure class is fixed for a number of years.

This means that the CPI does not take into account changes in consumer behaviour in response to relative price changes (known as ‘substitution bias’). As a result, the forthcoming re-weighting is expected to reduce measured inflation, although it is hard to predict by how much because the effects of past re-weightings have varied significantly and are not necessarily a good guide to future episodes. The ABS plans to re-weight the CPI annually in future, which will reduce substitution bias on an ongoing basis.