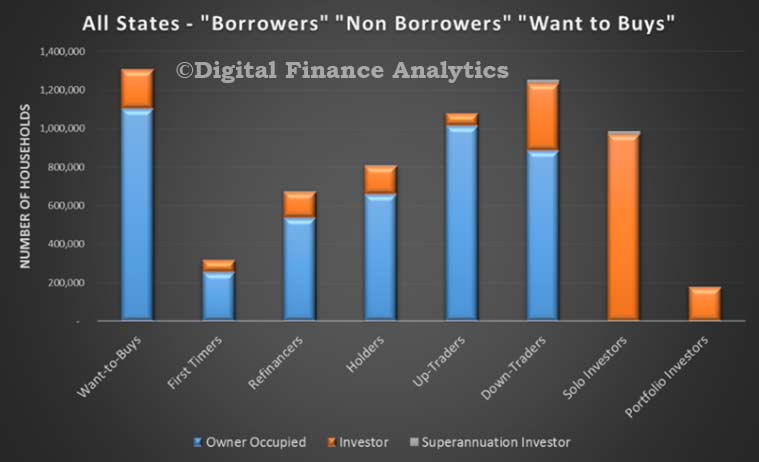

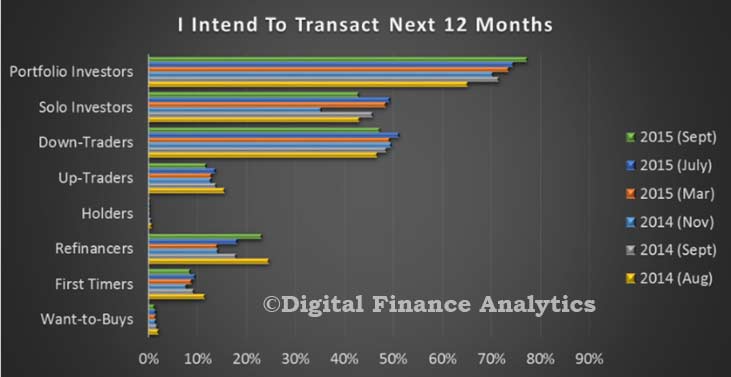

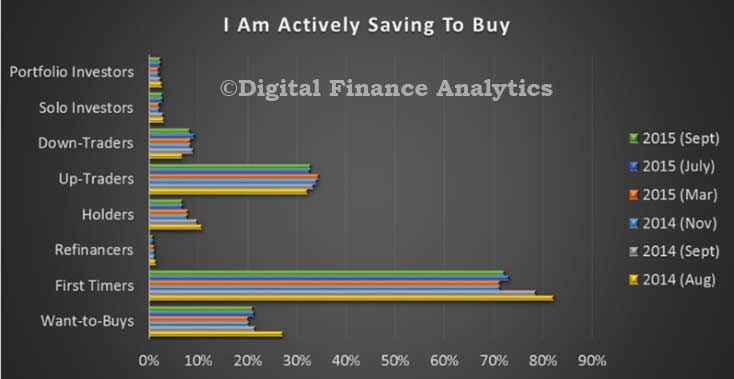

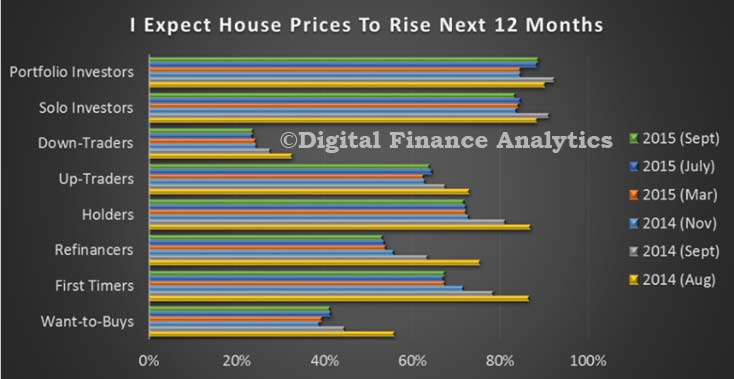

Continuing with data from the latest edition of the Property Imperative, today we look at first time buyers. Our latest survey identified about 319,000 households who are first time buyers. The majority are seeking to purchase, or have recently purchased an owner occupied property (80%), the remainder preferring an investment property. Only 9% of these households expect to transact within the next 12 months, despite 67% believing house prices are set to rise in the same term.

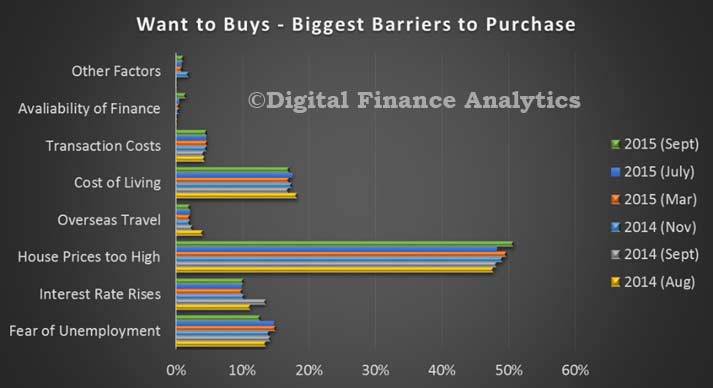

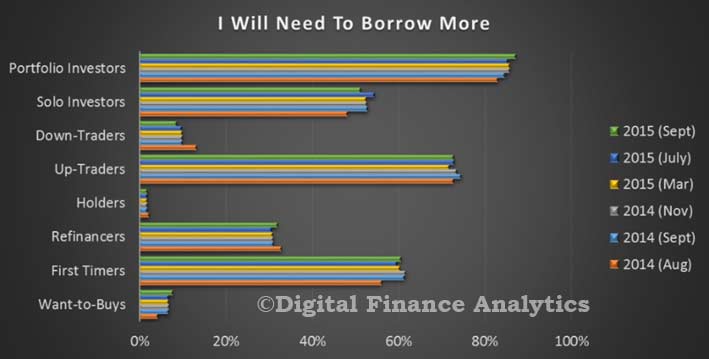

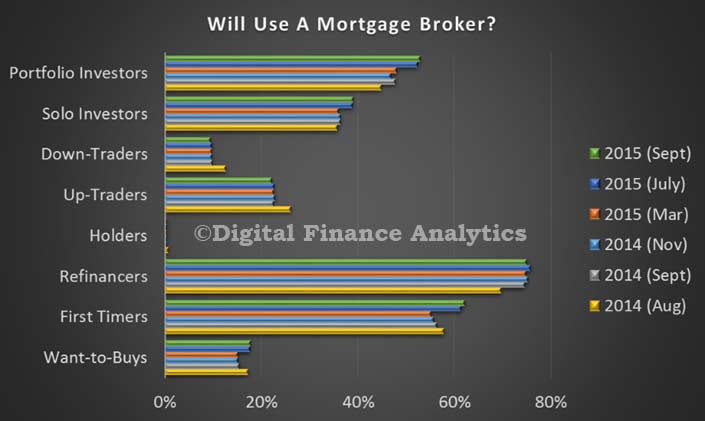

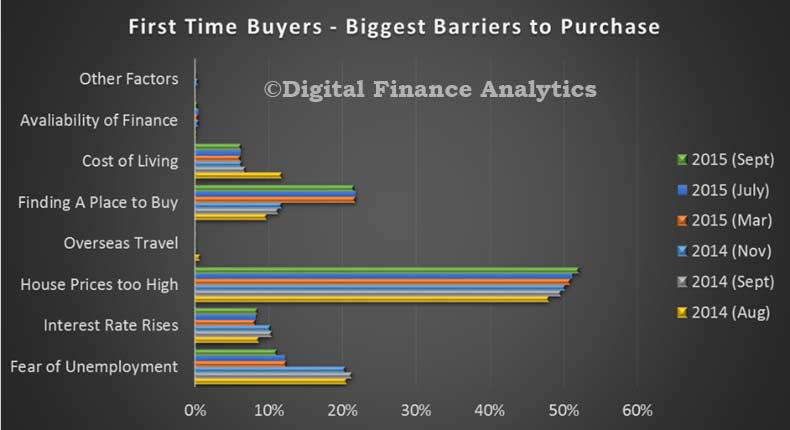

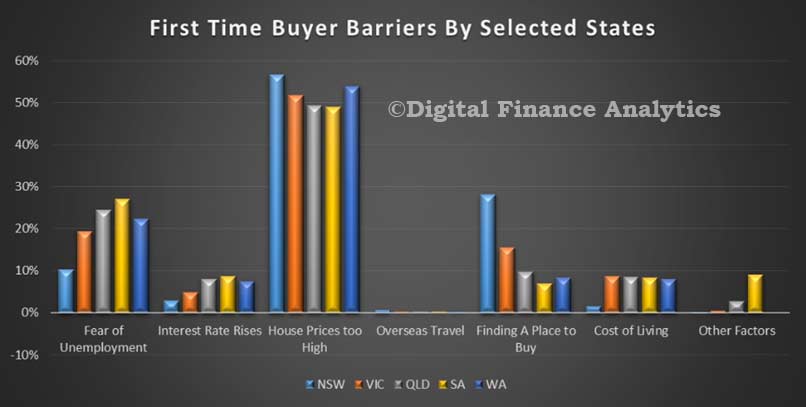

The biggest barrier to purchase include high house prices (52%), fear of unemployment (11%), finding the right property (22%) and rising costs of living (6%). In terms of financing 61% of households will need to borrow more than they can currently obtain to transact, whilst 62% of households will consider using a mortgage broker to assist with the finance arrangements.

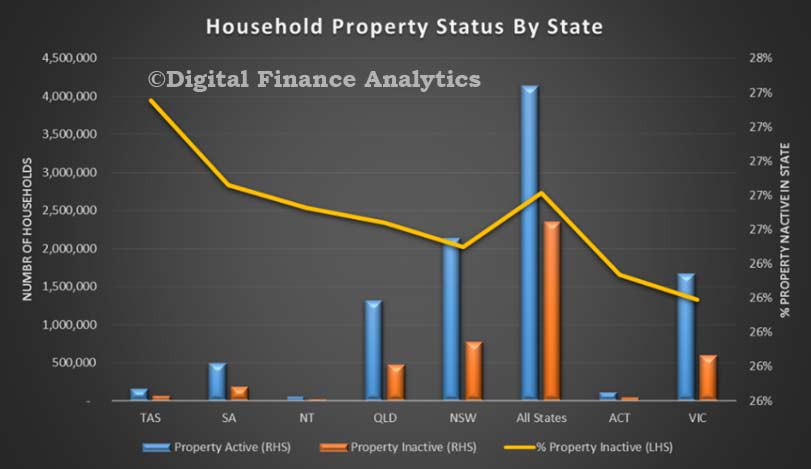

The barriers do vary by state. In NSW, first time buyers were finding it more difficult to find a suitable place to buy (28%), whereas costs of living were less significant here. In WA, fear of unemployment (22%) and high prices (54%) were the most significant barriers.

The barriers do vary by state. In NSW, first time buyers were finding it more difficult to find a suitable place to buy (28%), whereas costs of living were less significant here. In WA, fear of unemployment (22%) and high prices (54%) were the most significant barriers.

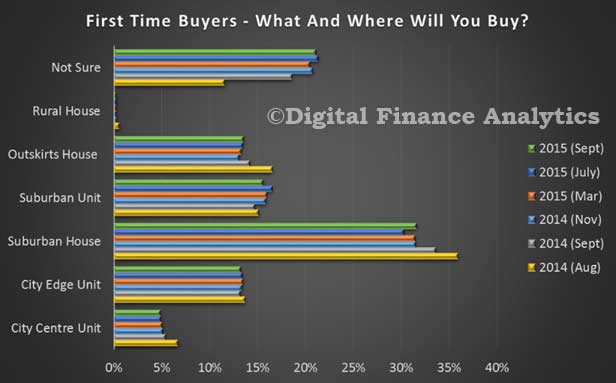

First time buyers are split between looking for a house or a unit (in Sydney more are looking for a unit). A greater proportion (21%) this time were simply not sure what to buy, or where to buy, a rise from 4% in 2013. A greater proportion of first time buyers in Sydney are likely to buy, or have bought a unit, rather than a house. In the other states, the preference for a house is stronger, though in Melbourne and Brisbane, it continues to drop. In Perth, house preferences are stronger.

First time buyers are split between looking for a house or a unit (in Sydney more are looking for a unit). A greater proportion (21%) this time were simply not sure what to buy, or where to buy, a rise from 4% in 2013. A greater proportion of first time buyers in Sydney are likely to buy, or have bought a unit, rather than a house. In the other states, the preference for a house is stronger, though in Melbourne and Brisbane, it continues to drop. In Perth, house preferences are stronger.

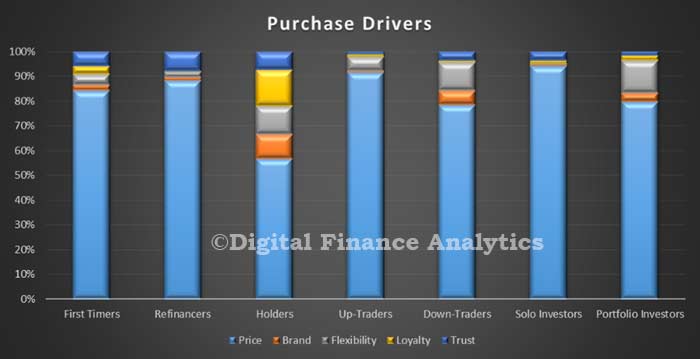

When we compared the elements which influence a buying decision, we see a stronger focus on price in 2015. Schools are important, then access to transport. We see consideration of absolute commute times to be less important now than in 2010. However, almost all elements are traded away because of high prices.

When we compared the elements which influence a buying decision, we see a stronger focus on price in 2015. Schools are important, then access to transport. We see consideration of absolute commute times to be less important now than in 2010. However, almost all elements are traded away because of high prices.

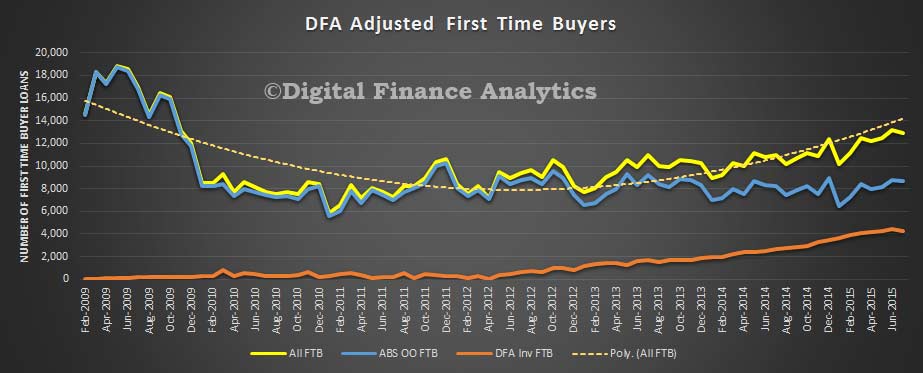

Whilst the ABS tweaked their estimates of first time buyers taking a mortgage to adjust for the decline in first owner grants, they still give an incomplete picture.

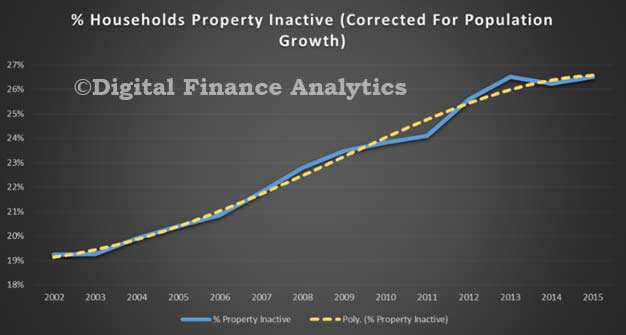

The traditional wisdom is that first time buyers are sitting out of the property markets, because prices are high, loans harder to get, and confidence is falling. However one of the most significant developments surrounding first time buyers is that many more are now going direct to the investment sector.

The original data from the ABS, shows a small fall in the month to 15.4% in July 2015 from 15.8% in June 2015. The DFA data for investor FTB also fell. The number of first time buyers are still sitting at around 12,000 a month in total, still well below the peaks in 2009. Our surveys indicate strong FTB investor appetite. The changed underwriting requirements however are having an impact.

There are a number of drivers to this trend. First, most first time buyers were unable to afford to purchase a property to occupy, in an area that made sense to them and were being priced out of the market. Next, many were anxious they were missing out on recent property gains, so decided to buy a less expensive property (often a unit) as an investment, thanks to negative gearing, they could afford it. They often continue to live at home meantime, hoping that the growth in capital could later be converted into a deposit for their own home – in other words, the investment property is an interim hedge into property, not a long term play. Some are also teaming up with friends to jointly purchase an investment, so spreading the costs. In fact about one third who purchased were assisted by the Bank of Mum and Dad, and would consider an investment property by accessing their superannuation for property investment purposes, a bad idea in our view.

There are a number of drivers to this trend. First, most first time buyers were unable to afford to purchase a property to occupy, in an area that made sense to them and were being priced out of the market. Next, many were anxious they were missing out on recent property gains, so decided to buy a less expensive property (often a unit) as an investment, thanks to negative gearing, they could afford it. They often continue to live at home meantime, hoping that the growth in capital could later be converted into a deposit for their own home – in other words, the investment property is an interim hedge into property, not a long term play. Some are also teaming up with friends to jointly purchase an investment, so spreading the costs. In fact about one third who purchased were assisted by the Bank of Mum and Dad, and would consider an investment property by accessing their superannuation for property investment purposes, a bad idea in our view.

Given the heady state of property prices at the moment, this growth in investment property by prospective first time buyers is on one hand logical, on the other quite concerning. We would also warn against increasing first time buyer incentive.

Remember, also the data refers to loans, not property transfers, and we know from our surveys that additional purchases were made without the need for a mortgage by overseas investors, and local purchases cashed up thanks to the Bank of Mum and Dad.

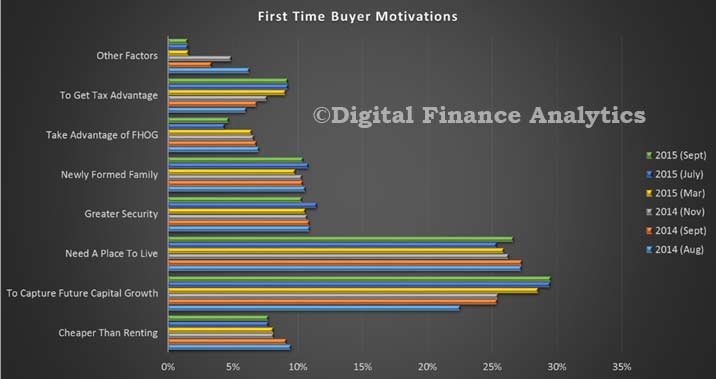

Turning to the reasons why first time buyers are going down this track, our analysis of buyer motivations draws some striking observations. We see that the prospect of potential capital gains is now the highest rated driver at 30%, whilst the desire for somewhere to live is just 27%. We see the prospect of gaining tax advantage is growing, now up to 10%, whilst the advantage of a First Home Owner Grant (FHOG) is falling away as these grants become less accessible (6%). Fewer buyers now expect to pay less than renting, whilst the prospect of greater security remains about the same.

So putting this together, we conclude that first time buyers are reacting to the current house price boom in logical ways. They are however being infected by the notion that property is about wealth building, rather than somewhere to live. This notion, which served previous generations quite well (once they were on the property escalator), may be tested if interest rates rise later, or property prices fall from their current illogical stratospheric levels. The overriding result from the survey is the first time buyers are very fearful of missing out, and that delaying potential entry into the market will simply make it less affordable later. Recent changes to underwriting standards may cramp their style, but we still expect to see a continued rise in the number of first time investor buyers.

So putting this together, we conclude that first time buyers are reacting to the current house price boom in logical ways. They are however being infected by the notion that property is about wealth building, rather than somewhere to live. This notion, which served previous generations quite well (once they were on the property escalator), may be tested if interest rates rise later, or property prices fall from their current illogical stratospheric levels. The overriding result from the survey is the first time buyers are very fearful of missing out, and that delaying potential entry into the market will simply make it less affordable later. Recent changes to underwriting standards may cramp their style, but we still expect to see a continued rise in the number of first time investor buyers.