As we come to the end of 2019, you’d be forgiven for being confused about the health of the economy. Via The Conversation.

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg regularly points out that jobs growth is strong, the budget is heading back to surplus, and Australia’s GDP growth is high by international standards.

The opposition points to sluggish wages growth, weak consumer spending and weak business investment.

Monday’s Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) provides an opportunity for a pre-Christmas stock-take of treasury’s thinking.

1. Low wage growth is the new normal

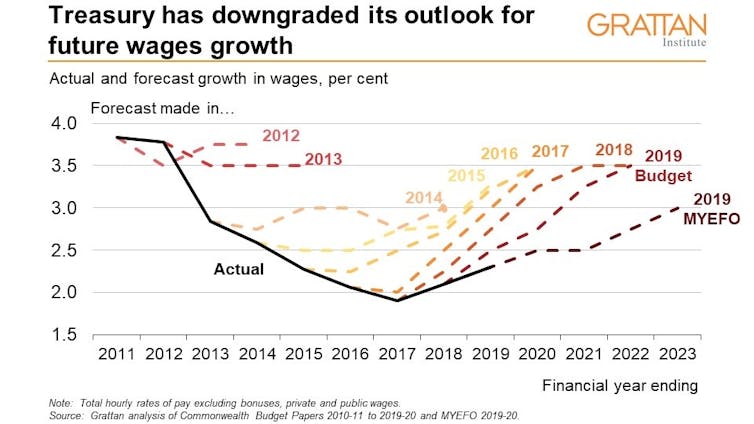

Rightly grabbing the headlines is yet another downgrade to wage growth.

In the April budget, wages were forecast to grow this financial year by 2.75%. In MYEFO, the figure has been cut to 2.5%.

Three years ago, when Scott Morrison was treasurer, the forecast for this year was 3.5%.

Each time wages forecasts missed, treasury assumed future growth would be even higher, to restore the long-term trend.

Today’s MYEFO is a long-overdue admission from treasury that labour market dynamics have shifted – in other words, lower wage growth is the “new normal”.

Even by 2022-23, wages are projected to grow at only 3% (and even that would still be a substantial turnaround compared to today).

Of course, wages are still rising in real terms (that is, faster than inflation), a fact Finance Minister Mathias Cormann is keen to emphasise.

But Australians will have to adjust to a world of only modest growth in their living standards for the next few years.

2. Economic growth is underwhelming, especially per person

Economic growth forecasts have received a pre-Christmas trim.

Treasury now expects the economy to grow by 2.25% this financial year, down from the 2.75% it expected in April.

Particularly striking is the sluggishness of the private economy, with consumer spending expected to grow by just 1.75%, despite interest rate and tax cuts, and business investment idling at growth of 1.5%, down from the 5% forecast in April.

The longer term picture looks somewhat better, with growth forecast to rise to 2.75% in 2020-21 and 3% in 2021-22, although treasury acknowledges there are significant downside risks, particularly from the global economy.

The government has made much of the fact our economy is strong compared to many other developed nations. But much more relevant to people’s living standards is per-person growth. Australia’s international podium finish looks less impressive once you account for the fact Australia’s population is growing at 1.7%.

As one perceptive commentator has noted, while Australia is forecast to be the fastest growing of the 12 largest advanced economies next year, it is expected to be the slowest in per-person terms.

3. The government is at odds with the Reserve Bank

You can imagine the government’s collective sigh of relief that it is still on track to deliver a surplus in 2019-20, albeit a skinny A$5 billion instead of the the $7 billion previously forecast.

Given the treasurer declared victory early by announcing the budget was “back in the black” in April, missing would have been awkward, to say the least.

And another three years of slim surpluses are forecast ($6 billion, $8 billion and $4 billion respectively).

The real issue for the treasurer is how to deal with the growing calls for more economic stimulus, including from the Reserve Bank.

Depending on what happens to growth and unemployment in the first half of 2020, he will come under increased pressure to jettison the future surpluses to support jobs and living standards.

4. High commodity prices are a gift for the bottom line

High commodity prices are the gift that keeps on giving for the Australian budget.

Iron ore prices in excess of US$85 per tonne, well above the US$55 per tonne budgeted for, have helped to keep company tax receipts buoyant.

Treasury is maintaining the conservative approach it has taken in recent years by continuing to assume US$55 per tonne.

This provides some potential upside should prices stay high – Treasury estimates a US$10 per tonne increase would boost the underlying cash balance by about A$1.2 billion in 2019-20 and about A$3.7 billion in 2020-21.

The budget bottom line remains tied to the whims of international commodity markets for the near future.

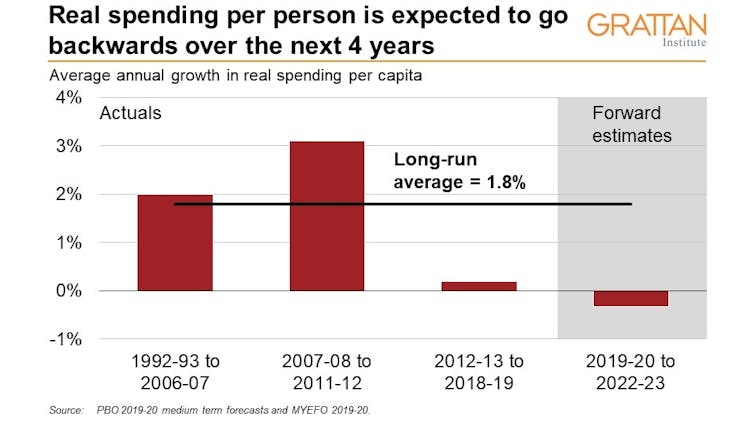

5. The surplus depends on running a (very) tight ship

The forecast surpluses over the next four years are premised on an extraordinary degree of spending restraint.

This government is expecting to do something no government has done since the late-1980s: cut spending in real per-person terms over four consecutive years.

The budget dynamics are helping. Budget surpluses and low interest rates reduce debt payments, and low inflation and wage growth reduce the costs of payments such as the pension and Newstart.

But the government is also expecting to keep growth low in other areas of spending, in almost every area other than defence and the expanding national disability insurance scheme.

As the Parliamentary Budget Office points out, it is hard to keep holding down spending as the budget improves.

It is even more true while long term spending squeezes on things such as Newstart and aged care are hurting vulnerable Australians.

Where does it leave us?

The real lesson from MYEFO is that Australians are right to be confused: there is a disconnect between the health of the budget and the health of the economy.

MYEFO suggests both that the government is on track to deliver a good-news budget surplus underpinned by high commodity prices and jobs growth, and that the economy is in the doldrums with low wage growth in place for a long time.

Top of Frydenberg’s 2020 to do list: how to reconcile the two.

Authors: Danielle Wood, Program Director, Budget Policy and Institutional Reform, Grattan Institute; Kate Griffiths, Senior Associate, Grattan Institute