What is driving long-term interest rates lower around the world lower is not asset purchases or otherwise distortive monetary policies, but rather global economic circumstances that are expected to require very low policy rates for many years. The ongoing effects from debt deleveraging and shifts in demographics the distribution of income may lead, for many years to come, to substantially lower interest rates than we have seen in the past.

In a speech to the London Business School, external Bank of England MPC member Gertjan Vlieghe, explores the reasons for low long-term interest rates. “Long-term interest rates play an important role in monetary policy.

In a speech to the London Business School, external Bank of England MPC member Gertjan Vlieghe, explores the reasons for low long-term interest rates. “Long-term interest rates play an important role in monetary policy.

They are a key part of the transmission mechanism, via which monetary policy affects the wider economy.

And they contain useful information about expected future policy rates and expected future inflation.”

Jan also reflects on the current UK outlook. He says that the EU referendum has caused increased uncertainty and poses challenges for the MPC in assessing how much of the continued slowdown in GDP growth “is due to the referendum, an effect which should be short-lived, and how much of it reflects a more fundamental loss of underlying momentum, which might be more persistent”. Given this, following the referendum he “would like to see convincing evidence of an improvement in the economic outlook, in line with the forecasts in the May Inflation Report. If such improvement is not apparent soon, this will reduce my confidence that inflation is likely to return to the target within an acceptable time horizon without additional monetary stimulus.”

In the UK, long-term interest rates have been coming down gradually since the early 1980s and the current 10 year bond yield is now about 1.5%.

Jan decomposes long-term interest rates into real and nominal components as well as expectations and risk premia components. He finds that “the most important factor behind the fall in long-term interest rates since the financial crisis has been a downward revision in the expected path of policy rates, with inflation expectations relatively stable, thus reflecting lower expected future real rates”.

This analysis suggests that “the reason expected future real rates are low is that monetary policy has responded, and is expected to continue to respond, appropriately to persistent forces weighing on demand and inflation”.

The analysis also suggests asset purchases have not “distorted” government bond yields. Instead, the main effect of asset purchases on long-term interest rates appears to have been due to the signal sent by purchases about the Bank’s reaction function and thereby led to a downward revision of the expected future path of interest rates. This finding also “sheds light on the likely impact of unwinding asset purchases”.

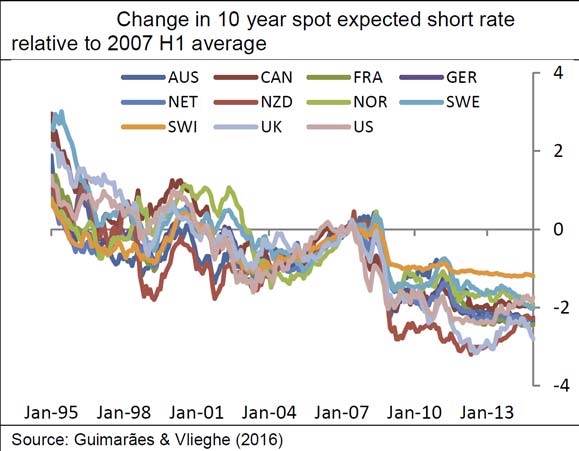

Finally, Jan applies the same decomposition to a range of countries with varying monetary policies all of which show “a substantial fall in the expected path of future interest rates” with the path of future policy rates “revised down by several percentage points on average.” This suggests that “what is driving long-term interest rates lower is not asset purchases or otherwise distortive monetary policies, but rather global economic circumstances that are expected to require very low policy rates for many years”.

This supports Jan’s argument in his speech in January that ongoing effects from debt deleveraging and shifts in demographics the distribution of income may lead, for many years to come, to substantially lower interest rates than we have seen in the past.