With property prices at dramatic highs, regulators are getting very nervous about the danger of a shakeout, so they’re trying to chase away investors by making loans harder to get and more expensive.

While the dangers of over-exposure to a property slump through unaffordable mortgages and aggressive negative gearing strategies are clearly understood, there’s another property-related danger lurking in the wings: bank shares.

The banks have been massive winners from the property boom. The lure of easy money from jumping prices has seen them dramatically lift exposures to residential housing, from 47 per cent of their loan portfolios in 1997 to 66 per cent today.

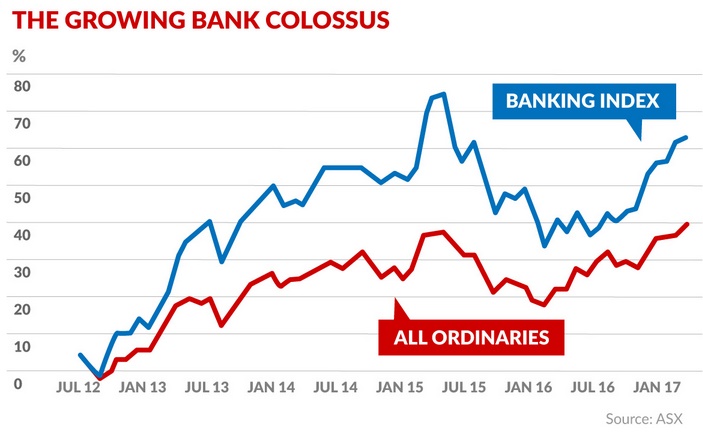

And, as The New Daily recently reported, housing lending has left business lending for dead since capital gains discounts were introduced in 1999. So profitable have banks been they now make up 32 per cent of the value of the Australian share market and, as the following chart shows, they are outgrowing the rest of the market.

But that all leaves them, and investors, highly exposed to property fortunes, according to a new report from investment consultants Rice Warner.

“Australians have been heavily invested in the domestic banking sector due to its high visibility, perceived strong track record (despite the GFC) and size relative to the rest of the Australian market. However, institutions in this sector are, by nature, highly interlinked … on mortgage lending,” the report said.

The interrelationship between bank profits and the property boom has worked in tandem. “But when one starts to fall I won’t be surprised if the other goes down with it,” Michael Berg, a senior consultant with Rice Warner, said.

And private investors, many of them retirees, would be heavily hit by falling bank shares. “Whenever we see a breakdown it shows portfolios are heavily weighted to bank shares,” Mr Berg said.

“It’s fair to draw attention to the very high weightings in portfolios to bank shares,” said independent economist Saul Eslake. “The main reason they’re so attractive is they deliver very high after-tax yields through dividend imputation.”

However if the property market were to fall “the banks may well cut their dividends”, Mr Eslake said. That, in turn, would hit their prices.

A fall in bank share prices and dividends would hit not only the 26 per cent of Australians who have direct share investments it would also hit retirees exposed to shares through super funds.

Self-managed super funds and retail, in particular, are heavily exposed to shares which deliver high dividends. Their members would see incomes cut if prices and more particularly dividends, were cut.

Industry funds also have shares but they tend to have lower exposures than retail funds because they often invest collectively in other asset types.

Another share popular with retirees for its dividends is Telstra, which has fallen 25 per cent since January because of concerns about competition in its markets reducing future profits. “The scary part (with the banks) is when you look what’s happened to Telstra,” said David Simon, principal of advisory group Integral Private Wealth.

“The banks could be facing similar risks.”

Given the fact that many portfolios are made up of at least 20 per cent bank shares, a property-induced banking shakeout would be felt widely, hitting peoples’ retirements and the economy generally as incomes and spending falls.