From The Conversation.

This is longer than the usual Conversation article, so allow some time to read and enjoy.

The crisis really is in real wage growth. – Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe, 2017

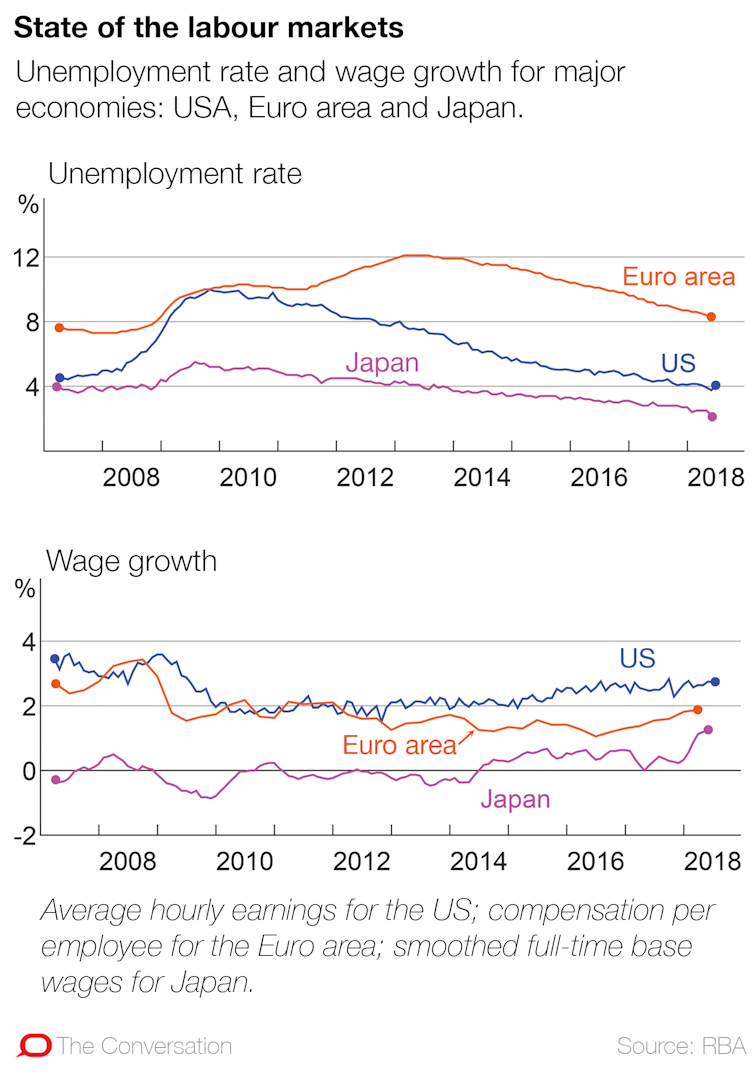

Increased inequality and low wage growth are constraining economic growth. But why is wage growth so low? And how should policymakers respond?

Income inequality has increased significantly in most advanced economies since the early 1980s. In particular, very low rates of wage increase are widely blamed for the weak growth in aggregate demand this century and secular stagnation since the Global Financial Crisis. The GFC was itself brought on by the rise in consumer debt that was used at first to support demand in an attempt to offset the impact of weak wage growth.

Fairfax columnist Ross Gittins recently noted that “many economists were disappointed by this week’s news … that consumer prices rose only 2.1%”. That was because low inflation is “usually a symptom of weak growth in economic activity and, in particular, of weak growth in wages”.

Thus, today it is widely agreed that wages need to increase faster. The OECD, the IMF, leading US scholars, former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, Nobel prize winner Joseph Stiglitz and most recently Stephen Bell and I in our book, Fair Share, have all argued that increasing inequality is bad for economic growth.

To solve this problem, the critical issue for policymakers is what is causing this rising inequality and weak wage growth? Unless we better understand the causes, we are unlikely to achieve an effective policy solution.

First, we can quickly dismiss the explanation offered by federal Treasurer Scott Morrison, whose so-called “economic plan” assumes present low wage growth will respond positively to higher company profits. According to Morrison, a company tax cut will lead to more investment and thus more jobs, so eventually the benefits will trickle down and increase wages.

Unfortunately, this logic is the reverse of reality. It ignores the evidence that slow wage growth across all the developed economies has been a problem over a couple of decades now.

In fact, the evidence strongly suggests higher profits will not drive higher wages. The benefits of a company tax cut will largely be returned to shareholders, while the only wages that increase will be those of senior management.

Instead, higher investment will require increased consumer demand. And that in turn depends on stronger wage growth. In short, aggregate demand in a flat economy, like ours, is wages-led. Wages drive investment, not the other way around.

Broadly speaking, there are two serious schools of thought about what is causing weak wage growth and rising inequality.

One explanation puts most of the blame on a weakening of trade-union power.

The other explanation emphasises the impacts of technological change and, to a lesser extent, globalisation on the labour market. Together technology and globalisation are said to have changed job structures and demands for skills. They have reduced the share of middle-level jobs, which has directly increased income inequality, and they can depress the demand for labour more generally and thus wages in developed countries, but especially for less skilled labour.

These two explanations are not mutually exclusive – both may have played a role. However, I want to consider their relative significance as the basis for arguing which policy responses should be given priority.

Trade union power in Australia and its impact

A very distinguished professor of labour economics and former Industrial Relations Commission deputy president, Joe Isaac, recently argued persuasively that an important explanation of slow wage growth is “to be found in the change in the balance of power in favour of employers and against workers and unions”.

Isaac starts by noting that union membership in Australia has fallen from about 50% of all employees in the 1970s to the present 15%. This is one of the lowest rates in the OECD.

Isaac also finds some correlation between income inequality (measured by the Gini coefficient) and trade union density for 11 OECD countries. More relevant, though, would be the change in inequality relative to the change in union membership, especially as Australia has always had a relatively high Gini coefficient.

Isaac argues that this loss of membership and the reduced authority of the Fair Work Commission has weakened the bargaining power of organised labour in Australia. Employers are now able “to determine no wage increase or an increase less than their profits would warrant, with less resistance from workers and unions”. Although Isaac admits that “this conclusion is based on the association over time of union power decline and slow wages growth”, he concludes that “it seems reasonable to claim, at least prima facie, a causal connection between them”.

I am more sceptical. While I wouldn’t rule out any impact on wages and employee conditions from a decline in trade union membership and the possibly associated changes in the power of the Fair Work Commission, I question Isaac’s analysis for the following reasons.

First, it is uncertain how much trade union power has declined as a result of loss of membership. Another test of trade union power is the proportion of wages determined by awards and collective agreements – as Isaac shows, this proportion has largely remained the same in Australia. Indeed, in some countries, such as France, trade union membership has always been very low, but they have a highly centralised system of wage determination, which allows the unions a lot of influence.

Second, other countries have also experienced increases in inequality – much greater than in Australia in most cases – but don’t seem to have experienced any notable loss of union power. For example, some of the biggest increases in inequality over the last 30 years, as measured by the Gini coefficient for final disposable income, have occurred in countries like Sweden, Finland and Germany, which are not associated with any loss of trade union power.

Third, Isaac’s analysis of wage inequality focuses entirely on a decline in the wage share of total factor income. This ignores changes within the distribution of earnings. These latter changes are more important in many countries, and certainly for Australia.

While the wage share in Australia has declined since the 1970s and early 1980s, this was at least partly a result of deliberate policy under the Hawke/Keating governments’ Accord with the trade unions, when it was accepted that the wage share had been too high. Even today the wage share is still higher than in 1960, when the economy was generally considered to be performing exceptionally well.

Fourth, the changes in the distribution of earnings largely reflect changes in the structure of occupations rather than changes in relative wage rates. But trade unions seek to influence wage rates, and it is difficult to see how they can exert much direct influence over the structure of jobs.

For these various reasons, I don’t think the loss, if any, of trade union power can explain much of the increase in inequality in most countries over the last 30 years. It is necessary to look elsewhere for the explanation, and the main driver seems to have been the impact of technological change.

Impacts of technology and globalisation

In Fair Share, Stephen Bell and I examine the causes of increased inequality over the last 30 years in most of the advanced economies. A critical starting point is to distinguish between changes in the job structure and changes in relative wage rates. As we note:

Even if there were no change in relative wage rates, but employment increased faster for both high-paid and low-paid jobs, the earnings distribution would show up as more unequal. What would have happened is that the composition of the top and lowest deciles of earnings would have altered, which would increase the median income of the top decile and reduce the median income of the lowest decile, which would in turn be reported as an increase in the inequality of earnings.

The consensus in the studies we reviewed is that increased inequality of earnings largely reflects the impact of technological change. Globalisation and increased participation in global value chains may also have played a role, but less so in Australia, which we attribute to Australia having a more flexible labour market than, say, America.

We also surmise that increased financialisation and the capture of rents generated by technological change may help explain the very large increase in remuneration for the top 1%.

Interestingly, the OECD specifically rejected the hypothesis that regulatory changes have helped drive any significant increase in inequality. It found that “the net effect of regulatory reforms on trends in ‘overall earnings inequality’ remains indeterminant in most cases”.

The principal impact of technological change, and globalisation to a lesser extent, has been to reduce the share of middle-level jobs. In particular, new information and communications technology has had its greatest impact on relatively routine tasks involving middle-level jobs, such as clerical occupations and the operation of basic machinery.

Technological change has also driven the fall in the relative price of capital goods. This has led to some substitution of capital for labour. Again, this is “particularly pronounced in industries with a high predominance of routine tasks”, as the OECD notes.

These changes in job structure and the relative decline in the middle-level jobs have been the most important cause of increasing inequality in many countries, including Australia. Technological progress has also led to an increase in the demand for skills. In some countries that has increased the premium paid for skilled labour, but the extent of this depends upon the policy response affecting the supply of skills.

In Australia’s case, Bell and I find that the premium for skills, and consequently relative wage rates, did not change much because of the increase in education and training effort. Accordingly, much of the increase in earnings inequality in Australia reflects changes in the job structure rather than changes in relative wage rates (see also Keating and Coelli & Borland).

So what does this mean for policy?

Consistent with his view that a weakening of trade union power has driven the increase in inequality, Isaac recommends changing the Fair Work Act to rectify “the unbalanced industrial power in the labour market”. I can support most of Isaac’s recommended changes, and especially greater rights of union entry, which should help better police adherence to awards and wage agreements.

I also agree that Isaac’s recommended legislative changes are unlikely to result in unions abusing their increased power. This is because, as he puts it, “there are now prevailing forces, such as global competition and structural changes, which will continue to keep union power in check”.

However, these “prevailing forces” are what really caused most of the increase in inequality, as discussed above. I therefore doubt that these legislative changes will do much to reverse the increase in earnings inequality.

Instead, the best way to respond to the impact of technological change on the job structure and possible associated changes in wage premiums is to improve education and training. Enhanced education, training and labour market policies will help workers adjust to the challenges posed by new technologies and will also spur the adoption of those technologies.

In addition, if the supply of skills thereby increases in line with the increase in their demand, there should not need to be any change in relative wage rates. Although these types of reforms take time, in the end they can boost both aggregate demand and potential output, with benefits all round.

In short, as Thomas Piketty, in his major study on inequality, concluded:

To sum up: the best way to increase wages and reduce wage inequalities in the long run is to invest in education and skills.

Author: Michael Keating Visiting Fellow, College of Business & Economics, Australian National University