Interesting speech from Wayne Byers “Reflections on a changing landscape“. He discussed the ” extraordinary intervention” to save our banks a decade ago (in a footnote), significant in my view, for what it said, and for what it missed out. There is no mention that both NAB and Westpac required bailing out by the FED’s TAF after the GFC. An important little fact?

APRA’s activities have expanded significantly over the past five years. This has not been a smooth transition: the regulatory pendulum has swung between periods of significant regulatory change, and times when there have been demands to pare back. But overall there is no doubt that expectations of APRA have grown, and they have pushed us into new fields of endeavour. There is no sign that tide is going to turn soon.

I’m not sure what the issues de jour will be in five years’ time but there’s a very good chance they will not be the issues we think are most important today. The past five years has shown that what might seem unusual or out of scope today, can quickly become a core task tomorrow. Some of the topics that I have talked about tonight were not seen, five years ago, to be at the heart of APRA’s role.

In contrast, later this week we will publish our 4 year Corporate Plan and a number of them will be called out as our core outcomes, ranking alongside maintaining financial safety and resilience.

If there is one lesson from the past five years, it is that – be it regulators or risk managers – being ready and able to respond to the demands of a rapidly changing landscape is probably the most important attribute we all need to possess.

But the footnote was the most interesting in my view. For what it said, and for what it missed out.

It is sometimes said the Australian banking system ‘sailed through’ the financial crisis. While the system did prove relatively resilient, there was extraordinary intervention necessary to keep the system stable and the wheels of the economy turning.

That included (i) an unprecedented fiscal response – one of the largest stimulus packages in the world;

(ii) an unprecedented monetary response – the official cash rate was cut by 425 basis points in a little over six months;

(iii) the RBA substantially expanded its market operations and balance sheet;

(iv) ASIC imposed an 8-month ban on the short selling of financial stocks; and

(v) the Federal Government initiated a guarantee of retail deposits of up to $1 million, and a facility for authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) to purchase guarantees for larger deposits and wholesale funding out to 5 years (indeed, at one point more than one-third of the banking system’s entire liabilities were subject to a Commonwealth Government guarantee).

As I have said previously, if all of the above was needed to keep the system stable and operational, then it is difficult to argue that the system sailed through or that some further strengthening of regulation was not justified.

He failed to mention the massive bail-out of our banking system from the FED and the fact that it was China’s response which supported our economy. The evidence suggests we were much closer to the abyss than was acknowledged at the time. Westpac and NAB both required support from the FED, as revealed in papers from the FED.

The US Dodd-Frank Act requires the US Federal Reserve to reveal which institutions it loaned money to under the various bail out programmes.

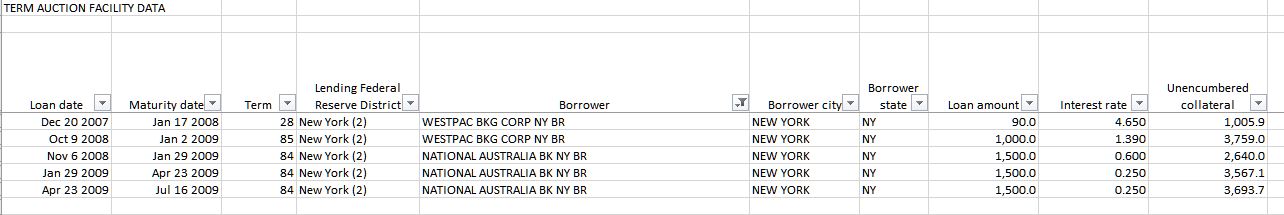

One of their programmes was the Term Auction Facility (TAF).

“Under the program, the Federal Reserve auctioned 28-day loans, and, beginning in August 2008, 84-day loans, to depository institutions in generally sound financial condition… Of those institutions, primary credit, and thus also the TAF, is available only to institutions that are financially sound.

Now of course the question is what does “financially sound” institutions mean. Well, look at the entire list – its long, but some of the names will be familiar. The FED data shows more than 4,200 separate transactions across more than 400 institutions globally between 2008 and 2010.

UK based Lloyds TSB plc received USD$10.5 billion – and was later partially nationalised by the UK government.

And another UK Bank, the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) got US$53.5 billion plus and additionally US$1.5 billion for its exposures via ABN Amro after RBS bought it. That was nationalised too.

In Ireland, Allied Irish Bank needed US$34.7 billion of loans from the Fed between February 2009 and February 2010 . This is the bank bailed out via the Irish taxpayer.

And Deutsche Bank needed a massive US$76.8 billion in loans in total (and that bank continues to struggle today).

The list goes on. Bayerische Landesbank required a US$13.4 billion bailout from the state of Bavaria, but also borrowed US$108.19 billion between December 2007 and October 2009.

Where these banks sound?

And our own “financially sound” institutions National Australia Bank and Westpac needed help from the Fed. NAB needed around $7 billion in total (allowing for the exchange rate).

In fact NAB raised $3 billion from shareholders in 2008 to add capital to its business in parallel.

And in January 2008 Westpac said everything was fine with its US exposures, just one month after they got their first bail-out from the FED, worth US$90 million.

In fact, there was a long queue then, as the Fed spreadsheet shows that alongside Westpac, was Citibank, Lloyds TSB Bank, Bayerische Landesbank and Societe Generale, all of whom where bailed out by Governments in their respective countries.

Now, the RBA wrote at the time:

“The Australian financial system has coped better with the recent turmoil than many other financial systems. The banking system is soundly capitalised, it has only limited exposure to sub-prime related assets, and it continues to record strong profitability and has low levels or problem loans. The large Australian banks all have high credit ratings and they have been able to continue to tap both domestic and offshore capital markets on a regular basis.”

So the question is did APRA and the RBA know what was going on?

And my question more generally is how prepared are we for a similar crisis now – given the changed economic and geopolitical forces in play?