To many, the required changes to capital under Basel III may seem obtuse and overly complex. So the timely speech given by Stefan Ingves, Governor of the Sveriges Riksbank and Chairman of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision is worth reading. He gives a clear articulation of why Basel III exists. Crises are expensive and should be avoided, he says.

When financial crises afflict us it becomes obvious to all how much damage they cause. Unfortunately, this insight is often temporary, as it is easy – even a human survival instinct – to forget problems and leave them behind us. As a representative of the Basel Committee I therefore see it as an important task to remind you of how costly financial crises are to the national economy and how important it is that we have robust regulatory frameworks that reduce both the cost of crises and the probability that they will occur.

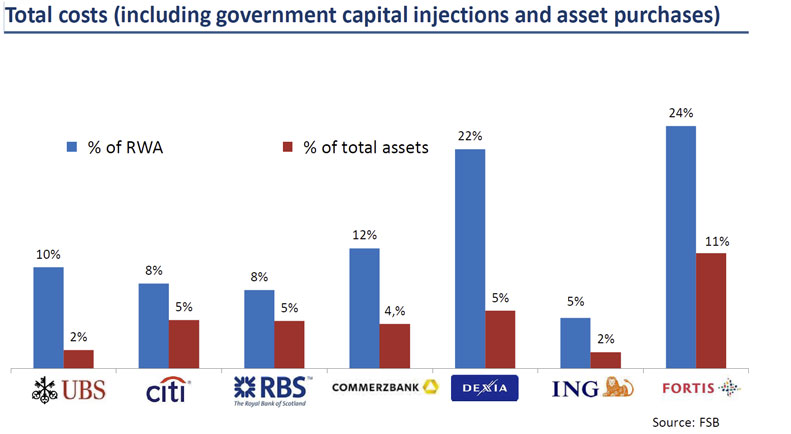

He showed this chart as a reminder of what happened after the GFC, as numerous and well know banks were bailed out.

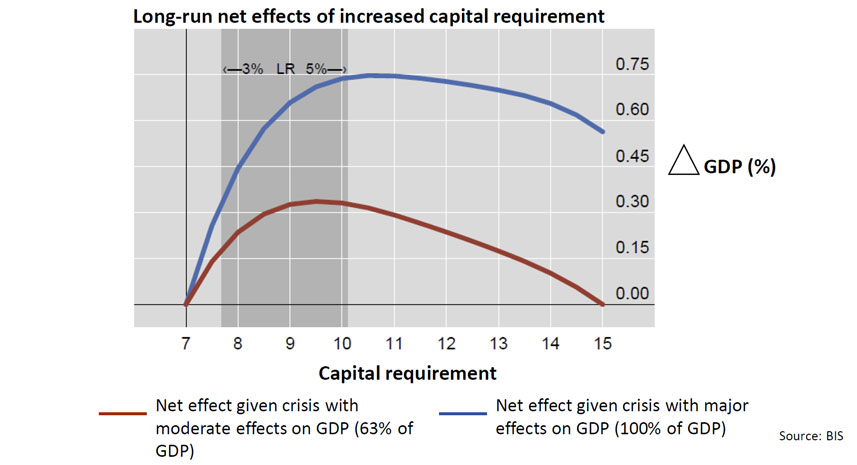

He also discussed the core assumption that increasing capital protects society, as well as the banks themselves.

He also discussed the core assumption that increasing capital protects society, as well as the banks themselves.

A crucial cause of the most recent financial crisis was that banks around the world had taken on too much risk. This was possible for two reasons. Firstly, the regulatory framework applying at the time did not sufficiently influence the banks’ risk taking. Secondly, the banks themselves evidently did not have the will or ability to manage their risks on their own. The answer was the Basel III Agreement – a comprehensive package of reforms with the main purpose of strengthening the banks’ capital base to ensure that they can manage losses in a better way and improve the banks’ liquidity management.

In 2013, the Basel Committee therefore published a number of reports analysing what capital requirements the banks’ internal models generated. The reports show that there are major differences in the banks’ capital requirements. They also show that these differences cannot be explained by the differences in the underlying risk in their assets, but are instead due to the way the banks measure risk. The fact that this is so not only makes it difficult to compare capital requirements between the banks, it also reduces the credibility of the international capital regulations. The Committee’s current work therefore concerns to a large extent ensuring that the models used by the banks are reliable and reflect the risks in their operations in a correct manner.

This work includes revising and to some extent limiting the banks’ scope to use internal models to calculate their risk-weighted assets and thereby their capital requirements. For instance, the Basel Committee is planning to introduce floors for a number of the parameters the banks estimate themselves. The result of this is that we will see less difference in the banks’ capital requirements for assets with similar risk profiles. Let me make myself clear: The idea is not that we shall return to Basel I. The banks will be able to continue using internal models in their risk management. What the Committee’s current work concerns is instead bringing order to the risk-based system to increase the credibility of the capital requirements the banks have and to make it easier to compare them. Without this work, there is a risk of further erosion of confidence in the regulations.

Another important part of the Committee’s work involves modernising and developing standard methods so that they become more risk sensitive and thereby better adapted to banks with international operations. For many types of exposure, such as lending with property as collateral, the current standard measures often give the same risk weight regardless of the loan-to-value ratio. This will probably be changed so that the capital requirement varies according to the loan-to-value ratio. This work also covers trying to reduce the mechanical dependence on external credit ratings, which is in line with the objectives stated by G20.

Critics have expressed fears that the reforms I am talking about now will lead to minimum capital for certain banks increasing radically, which in turn risks resulting in a real economic decline. Here I would like to point out that the Basel Committee’s ongoing reform work does not aim to significantly increase the total global capital requirements.

Instead, it concerns ensuring that all banks around the world have adequate resilience to manage financial crises and that risks are covered by capital in a uniform way in all banks and all countries. One result of this exercise is that banks that currently have very low risk weights will probably face higher capital requirements, while banks with very high risk weights may face lower capital requirements. Designing a uniform global regulatory framework is not an easy task, particularly as banking systems differ from country to country, but also because we are living in a changing world. The Basel Committee’s work is therefore largely a question of finding compromises that all member countries can support and which will stand the test of time.