As part of the discussion paper, released today APRA, says that addressing the systemic concentration of ADI portfolios in residential mortgages is an important element of the proposals. They have FINALLY woken up to the risks in the system, just years too late! We have significant numbers of loans in the system currently that would now not pass muster.

These proposals, which focus in on mortgage serviceability, would change the industry significantly, as lower risk loans will be more highly prized (so expect low rate offers for lower LVRs), whilst investment loans, and interest only loans are likely to cost more and be harder to find. Combined this could certainly move the market! The proposals introduce “standard” and “non-standard” risk categories.

The proposals are for consultation, with a closing data 18 May 2018.

As well as increasing the risk weights for some mortgages, they also continue to close the gap between the advanced (IRB) internal approach used by large lenders, and the standard approach used by smaller players. Those in transition (e.g. Bendigo Bank) may find less of an advantage in moving to advanced as a result.

Also they are proposing some simplification for small ADI’s as the cost of these measures may outweigh the benefit to prudential safety. Proportionate and tailored requirements for small ADIs could reduce regulatory burden without compromising prudential safety and soundness. Calibration of a simpler regime would be broadly aligned to the more complex regulatory capital framework, yet would be designed to suit the size, nature, complexity and risk of small ADIs.

Here are some of the key paragraphs from their paper.

APRA’s view is that there are potential systemic vulnerabilities to the financial system created from high levels of residential mortgage lending for investment purposes. As noted by the RBA, investment lending can amplify borrowing and house pricing cycles:

Periods of rapidly rising prices can create the expectation of further price rises, drawing more households in the market, increasing the willingness to pay more for a given property, and leading to an overall increase in household indebtedness.

Similarly, the significant share of interest-only housing lending, including to owner-occupiers, is a structural feature that increases the risk profile of the Australian banking system. Interest-only borrowers face a longer period of higher indebtedness, increasing the risk of falling into negative equity should housing prices fall. Borrowers may also use interest-only loans to maximise leverage, or for short-term affordability reasons. Even though loan servicing ability (serviceability) is now tested at levels that include the subsequent principal repayments, borrowers may face ‘payment shock’ when the interest-only period ends and regular repayments increase, in some cases significantly. This payment shock is particularly acute when interest rates are low.

Over the past two decades, residential mortgages in Australia as a share of ADIs’ total loans have increased significantly, from just under half to more than 60 per cent. While losses incurred on residential mortgage portfolios in this period have been limited, this level of structural concentration poses prudential and financial stability risks, particularly in an environment of high household debt, high property prices, weak income growth and strong competitive pressures among lenders. In such circumstances, households, individual ADIs and the broader banking sector are vulnerable to economic shocks.

Similar to other jurisdictions facing comparable risks, APRA has undertaken a series of actions to help contain the risks associated with ADIs’ residential mortgage portfolios. These actions include promoting significantly strengthened loan underwriting practices, increasing the amount of capital held by IRB ADIs for residential mortgage exposures and establishing benchmarks to moderate lending for property investment and lending on an interest-only basis. As set out in APRA’s July 2017 information paper on unquestionably strong capital, APRA also intends to further strengthen capital requirements for residential mortgage lending to reflect the concentration risk it poses to the banking sector.

A key focus is the appropriate capital requirement for investment and interest-only mortgage loans. Although, as a class, investment loans have typically performed well under normal economic conditions in Australia, this segment has not been tested in a nationwide downturn. Further, an increasing proportion of highly indebted households own investment property relative to past economic cycles. Experience in the United Kingdom and Ireland during the global financial crisis, for example, showed that previously better-performing investment loans can fall into arrears in higher volumes than loans to owner-occupiers in times of stress.

So now they propose to target higher-risk residential mortgage lending, balanced against the need to avoid undue complexity. Under the proposals, residential mortgage exposures would be segmented into the following categories with different capital requirements applying to each segment:

- loans meeting serviceability requirements made to owner-occupiers where the borrower’s repayment is on a principal and interest (P&I) basis;

- loans meeting serviceability requirements made for investment purposes or where the borrower’s repayment is on an interest-only basis; and

- other residential property exposures, including those that do not meet serviceability requirements.

Specifically, for the standard approach, APRA proposes that APS 112 would require ADIs to designate as non-standard eligible mortgages those where the ADI:

- did not include an interest rate buffer of at least two percentage points and a minimum floor assessment interest rate of at least seven per cent in the serviceability methodology used to approve the loan;

- did not verify that a borrower is able to service the loan on an ongoing basis (i.e. positive net income surplus); and

- approved the loan outside the ADI’s loan serviceability policy.

APRA is also considering excluding certain other categories of loans considered higher risk from the definition of standard eligible mortgages, such as those with very high multiples of a borrower’s income.

APRA proposes to formalise through amendments to APS 112 its existing requirement that loans to self-managed superannuation funds secured by residential property should be treated as non-standard loans, reflecting the relative complexity of these loans and the fact that ADIs do not have recourse to other assets of the fund or to the beneficiary.

APRA also proposes that reverse mortgages, which are currently risk-weighted at 50 per cent (where LVR is less than 60 per cent) or 100 per cent (for LVRs over 60 per cent), would be treated as non-standard in light of the heightened operational, legal and reputational risks associated with these loans.

Subject to final calibration, APRA proposes that all non-standard eligible mortgages would be subject to a risk weight of 100 per cent.

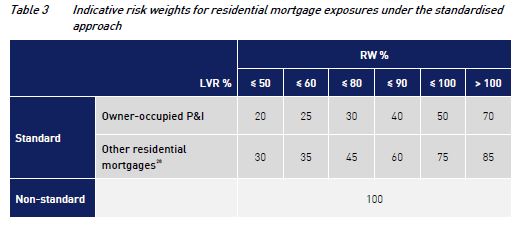

APRA proposes to segment the standard eligible mortgage portfolio into lower-risk and higher-risk exposures in addition to assigning risk weights according to LVR. This approach is aligned to, but deliberately not strictly consistent with, the Basel III ‘material dependence’ concept, to appropriately reflect Australian conditions.

For the lower-risk segment, APRA proposes to broadly align the risk weights with those under the Basel III framework loans where repayments are not materially dependent on cash flows generated by the property securing the loan. This category would include owner-occupied P&I loans and would apply after consideration of any lenders mortgage insurance (LMI).

The higher-risk segment would include interest-only loans, loans for investment property and loans to SMEs secured by residential property. The determination of higher risk weights for this segment would be either by way of a fixed risk-weight schedule, or a multiplier on the risk weights applied to owner-occupied P&I loans. The benefit of a multiplier is that APRA could more easily vary the capital uplift for these higher risk loans over time depending on prevailing prudential or financial stability objectives or concerns.

Table 3 shows the indicative proposed risk-weight schedule based on the Basel III risk weights for materially dependent residential mortgage exposures.

APRA is also considering whether exposures to individuals with a large investment portfolio (such as those with more than four residential properties) would be treated as non-standard residential mortgage loans or as loans secured by commercial property. APRA invites feedback on this issue.

APRA is also considering whether exposures to individuals with a large investment portfolio (such as those with more than four residential properties) would be treated as non-standard residential mortgage loans or as loans secured by commercial property. APRA invites feedback on this issue.

APRA expects to continue to incorporate relatively lower capital requirements in the standardised approach for exposures covered by LMI. LMI can reduce the risk of loss for an ADI, subject to meeting the insurer’s conditions for valid claims and the financial capacity of the LMI to pay claims. APRA is considering the appropriate methodology to recognise LMI in the capital framework for both the standardised and IRB approaches. For the standardised approach to credit risk, APRA expects that any capital benefit would continue to apply to loans with an LVR over 80 per cent. APRA’s preferred approach is to increase the Table 3 risk weights (as finally calibrated) for standard loans with an LVR over 80 per cent that do not have LMI. For the IRB approach, APRA is considering potential options for the recognition of LMI.

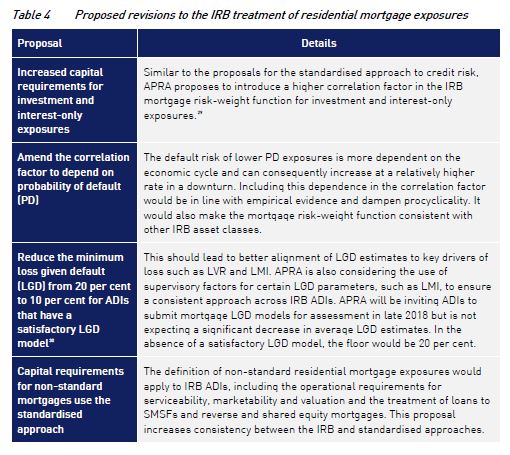

For IRB Bank (those using their own internal models, APRA believes that material changes are required in Australia in order to:

- improve the alignment of capital requirements with risk for particular exposures;

- further address the FSI recommendation that the difference in average mortgage risk weights between the standardised and IRB approaches is narrowed; and

- ensure an appropriate overall calibration of capital for residential mortgage exposures given the concentration of IRB ADI portfolios in this segment.

On their own, however, these IRB mortgage risk-weight functions are not expected to result in a sufficient level of capital to meet APRA’s objectives for increased capital for residential mortgage exposures. However, any further increase in correlation for the IRB mortgage risk-weight function creates inconsistencies with correlation factors for other asset classes.

On their own, however, these IRB mortgage risk-weight functions are not expected to result in a sufficient level of capital to meet APRA’s objectives for increased capital for residential mortgage exposures. However, any further increase in correlation for the IRB mortgage risk-weight function creates inconsistencies with correlation factors for other asset classes.

As a result, other adjustments are likely to be necessary to meet unquestionably strong capital expectations. For residential mortgages, this is expected to be through additional RWA overlays on top of the outputs of the IRB risk-weight function, including both an overlay specifically for residential mortgages and an overlay for total RWA.

The exact form and size of these overlays will be determined after APRA has completed its QIS analysis. In determining final calibration of the regulatory capital requirement for residential mortgage exposures, APRA will consider the appropriate difference in the average risk weights under the IRB and standardised approaches, consistent with recommendation 2 of the FSI. As detailed in the final report of the FSI, given the IRB approach is more risk sensitive, some difference between the average risk weights for residential mortgage exposures under the different approaches to credit risk may be justified; however, it should not be of a magnitude to create unwarranted competitive distortions.

SME exposures secured by residential property that meet certain serviceability criteria would be included in the same category of exposures as residential mortgages for investment purposes and interest-only loans.

In APRA’s experience, these exposures have historically had higher losses than non-SME owner-occupier residential mortgage exposures.

For SME exposures that are not secured by property, APRA proposes to reduce the 100 per cent risk weight currently applied under APS 112 to 85 per cent. This gives some recognition to the various types of collateral, other than property, that SMEs provide as security. APRA does not propose to implement the Basel III 75 per cent risk weight for retail SME exposures, as there is insufficient empirical evidence that retail SME exposures in Australia exhibit a lower default or loss experience through the cycle than corporate SME exposures. SME exposures in this category would be limited to corporate entities where consolidated group sales are less than or equal to $50 million.