Within the 65 pages of the IMF report there is a comprehensive section on Australian house prices. Housing market risks they say remain heightened. They conclude that house prices are moderately overvalued, probably around 10 percent. The problem is concentrated in Sydney and is fuelled by investor credit and interest only loans. Current rates of house price inflation imply rising overvaluation. Current efforts to rein in riskier property lending might not be sufficiently effective.

International comparisons persistently signal warnings. The level of real house prices and the house price to income ratio is high relative to the OECD average (though similar to other buoyant markets). House price inflation picked up to 7-10 percent in 2014-15—driven by rapid increases in Sydney and to a lesser extent Melbourne (prices in the resource states have fallen back in recent months). While foreign investment in real estate has increased, the main driver has been local investor lending and interest-only loans. Sydney house price to income ratios are much higher than for other cities at around 7—similar to Auckland, London, Stockholm and Vancouver.

Can the increase in house prices be explained?

- The housing market and financial system have changed significantly over the past two decades with a shift to low inflation, low nominal interest rates and financial liberalization which loosened credit constraints. Households’ borrowing capacity increased and they moved to a higher steady state level of indebtedness and higher house prices relative to incomes.

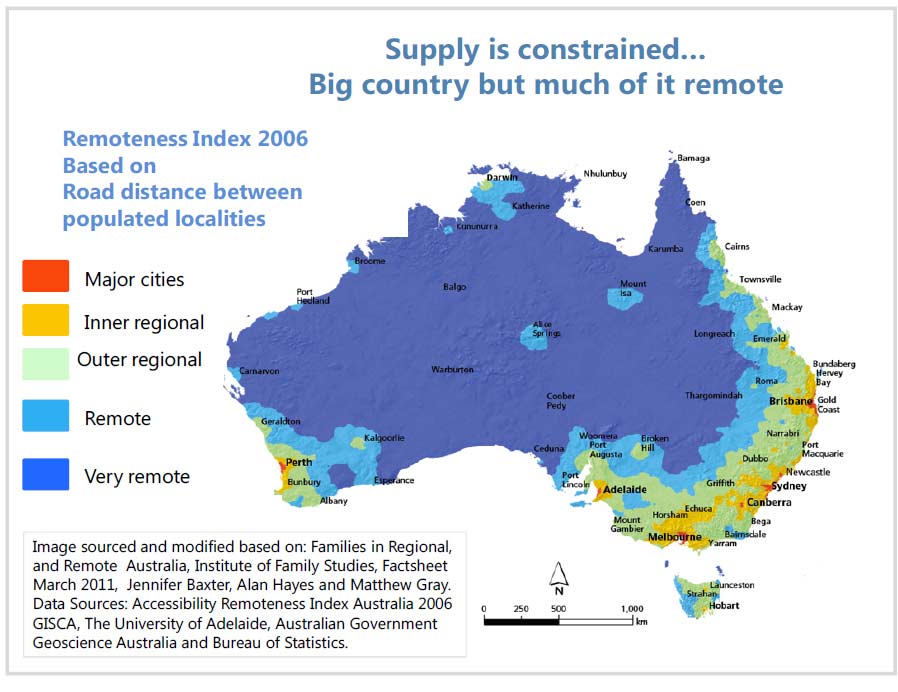

- Supply side constraints may also keep prices high. Although Australia is big, much of the country is remote and the population is concentrated in a few cities where there are geographical or other barriers to expansion. Population growth has also been much more rapid than for other OECD countries, whereas housing investment as a share of GDP is only at OECD average levels. Supply bottlenecks also reflect planning issues and transport restrictions.

Are high and rising prices a problem? There has been no generalized credit boom and lending standards are generally high (and being tightened), so financial stability risks seem contained. The run-up in house prices has also not been accompanied by a construction boom (unlike Ireland and Spain). But with already high debt and house prices, rapid house price inflation raises the risk of a sharp reversal, which would damage the macroeconomy.

Do models point to overvaluation? Estimating overvaluation is inherently difficult. Rather than relying on one model, staff used four different approaches.

- Statistical filter. Deviations from an HP filter suggest overvaluation of about 5 percent.

- Fundamentals. The standard model used in the Fund, estimated since the early 2000s, with fundamental explanatory variables—affordability, incomes, interest rates, and demographics―estimates overvaluation of around 15 percent and equilibrium growth rates around 3-4 percent.

- Including supply factors. A model using similar longrun fundamentals, but adding credit and the housing stock to take into account supply constraints, points to an overvaluation of around 8-10 percent.

- User costs. Estimates of user costs (whether it is more expensive to own than to rent) suggests that renting is about as costly as buying a house based on average real appreciation since 1955 (Fox and Tulip, 2014). However, this estimate is highly sensitive to interest rates and expectations of future house price appreciation. Using a plausibly lower expected appreciation term results in an overvaluation of 10-19 percent.

Bottom line: House prices are moderately overvalued, probably around 10 percent. The problem is concentrated in Sydney and is fuelled by investor credit and interest only loans. Current rates of house price inflation imply rising overvaluation.

In their house price modelling, they assume a baseline projection is for a soft landing, with house price inflation slowing to a sustainable 3-4 percent, based on medium-term fundamentals. This implies no change in the estimated overvaluation and housing market risks thus remain heightened.

Current efforts to rein in riskier property lending might not be sufficiently effective. Against a backdrop of already high house prices and household debt, this could give rise to price overshooting and excessive risk taking. A sharp correction in house prices, possibly driven by Sydney, could be triggered by external conditions (e.g., a sharper slowdown in China or a rise in global risk premia), or a domestic shock to employment.

This might have wider ramifications if it affects confidence. The house price cycle could be amplified by leveraged investors looking to exit the market and a turning commercial property cycle. Though currently small, investors in self managed superannuation funds that have added geared property to their fund portfolios would also be adversely affected in a downturn. In a tail scenario, APRA’s stress tests suggest banks would probably face ratings downgrades/higher offshore funding costs and would likely resist capital ratios falling into capital conservation territory by sharply tightening credit conditions, thus transmitting and amplifying the shock to the rest of the economy.