New data suggests that our four major banks are less well capitalised than you might expect, so today we discuss the implications.

Back in 2014, ex-Commonwealth Bank of Australia chief David Murray lead a financial system inquiry which recommended that Australia’s banks should maintain “unquestionably strong” status from a capital perspective. Specifically, to avoid issues in a crisis, the review recommended that they should be in the “top quartile” of banks globally relative to their international peers in terms of capital strength. All but one of his recommendations were accepted by the Government.

Back in 2014, ex-Commonwealth Bank of Australia chief David Murray lead a financial system inquiry which recommended that Australia’s banks should maintain “unquestionably strong” status from a capital perspective. Specifically, to avoid issues in a crisis, the review recommended that they should be in the “top quartile” of banks globally relative to their international peers in terms of capital strength. All but one of his recommendations were accepted by the Government.

Murray told The Australian Financial Review on Tuesday the “unquestionably strong” target was introduced to deal with two issues. The first was to ensure that if the government did have to support the banks in a crisis they would eventually get their money back. The second issue was to allow the banks to retain the faith of foreign investors in a systemic downturn, given the reliance on international debt capital markets.

APRA, the prudential regulator was then given the task of defining the “unquestionably strong” target that sharemarket investors at the time feared would force the banks to conduct dilutive capital raisings.

The banks have indeed increased their capital since 2014, but it was only in July 2017 that APRA provided clear guidance, setting a common equity tier one ratio target of 10.5 per cent. The banks were given 2½ years to achieve the modest uplift, and at the time bank stocks rallied on the limited targets and extended timeframes. APRA said the 10.5 per cent target also factored in expectations that global banks would increase their capital levels. Their subsequent papers did not change this fundamental target, even if the mix may change.

But despite being depicted by the government and the media as among the most secure in the world, the big four banks are no longer “unquestionably strong,” according to an S&P Global Ratings report released recently. The reason is their exposure to record levels of household debt and declining real estate values.

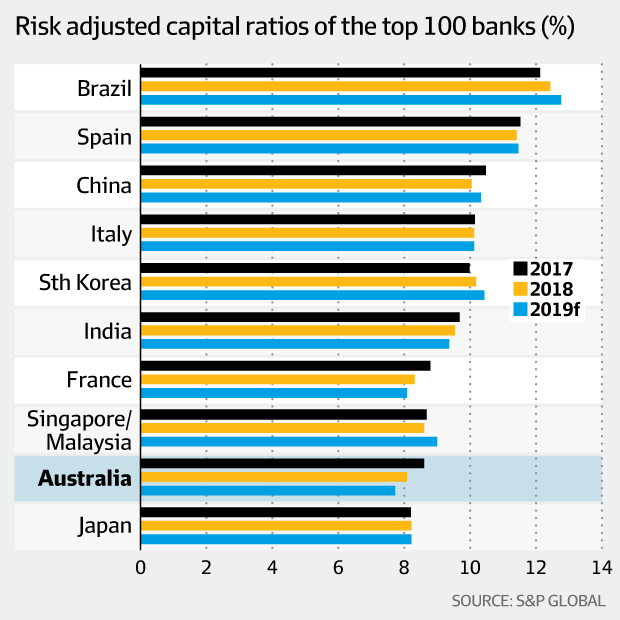

Based on a survey of 100 world banks compiled by S&P Global Ratings, Australian banks last year experienced among the “steepest declines” in their risk adjusted capital, or RAC, pushing them into the bottom half of global rankings. They would need to raise billions of dollars to return to the “unquestionably strong” top quarter of lenders.

This is because banks in other major economies bolstered their capital positions, while the economic risks posed by high levels of household debt and inflated property prices prompted S&P to penalise the Australian banks.

This is because banks in other major economies bolstered their capital positions, while the economic risks posed by high levels of household debt and inflated property prices prompted S&P to penalise the Australian banks.

This result, reported on the front page of the Australian Financial Review last Wednesday, but virtually nowhere else, is another indicator of a potential property and financial crash that would have devastating economic consequences, for the economy and households.

The capital decline has placed the four major banks around the 40th to 50th percentile of surveyed banks when ranked by the RAC ratio, the credit rating agency’s preferred measure of financial strength.

That is well outside the much trumpeted “top quartile” target set by regulators as a result of the David Murray-led 2014 Financial System Inquiry.

The AFR says that the S&P RAC ratio is calculated by dividing a bank’s total capital by its risk-weighted assets. The risk-weighted assets figure is adjusted by the agency based on the prevailing economic risk score of the country in which the bank operates.

The RAC scores of the big four banks range between 8.9 per cent (National Australia Bank) and 9.4 per cent (Commonwealth Bank).

That is below the average 10 per cent ratio that APRA said would “would improve the likelihood of being perceived by financial market participants as having unquestionably strong capital ratios”.

The RAC ratios do, however, factor in the agency’s dimmer view on the economic risks in Australia that had resulted from a build-up in household debt.

S&P’s decision in May 2017 to downgrade the economic risk score in Australia sliced about 90 basis points off the RAC ratios of the Australian banks, APRA said.

The prudential regulator said it preferred to calculate the RAC using a higher “normalised” economic risk score, which put the banks in the 10 per cent range.

But the S&P commentary is yet another signal of potential trouble ahead.