Australia will need another 730,000 social housing dwellings in 20 years if it is to tackle homelessness and housing stress among low-income renters. These are the findings of a new report from the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI), which shows social housing is in urgent need of direct public investment; via The Conversation.

Instead of directly investing in social housing, the federal government has sought to establish investment opportunities for other actors, such as pension funds and private corporations.

The vehicle for this investment is the National Housing Finance Investment Corporation (NHFIC), which was established to offer lower cost finance to social housing providers.

The federal government has also encouraged states and territories to focus public resources on supply, land policy reform and the use of planning methods such as inclusionary zoning to deliver affordable and social housing.

These initiatives are worthy, but they won’t generate enough new social housing supply on their own. Without direct public investment in the form of a needs-based capital investment program, the government is unlikely to fill the social housing gap.

Needs-based capital investment is where decisions on what to invest is not only based on financial return, but also on other factors like the effects on society (so infrastructure investment is one which is needs based).

And needs-based capital investment provides the most cost effective mechanism to influence the scale, location and quality of housing produced.

Social housing supply is dangerously lagging

The Australian Bureau of Statistics estimated 116,000 people were homeless in 2016, living in improvised and severely overcrowded homes.

Our further analysis of the 2016 Census shows 315,000 households rely on very low incomes, paying more than 30% of their income on rent. This is known as housing stress.

To address homelessness and housing stress right now, we need an additional 430,000 social housing dwellings. And this will grow over time.

Between 1951 and 1996, Australian jurisdictions built 8,000 to 14,000 social housing dwellings per year. In those years, social housing building programs were funded through direct public investment, with grants and long-term loans.

But without direct investment, social housing construction levels have languished since the mid 1990s.

In fact, the total number of Australian households increased by 30% from 1996 to 2016, and yet social housing grew by just 4%. This means there is a substantial backlog in supply, and the need for resources is now urgent.

Subsidies alone won’t cut it

It’s naive to think social housing systems can be adequately resourced through demand-side subsidies alone, such as cash support to tenants. In the UK, for instance, we’ve seen that while rent assistance budgets have grown, they haven’t helped to grow an affordable supply of homes, especially in tight, unregulated private rental markets.

In Australia, the Productivity Commission found that even after rent assistance is paid to eligible pensioners, 40.3% of them pay more than 30% of their incomes on rent. This leaves little for life’s other essentials, such as food, medical care and electricity.

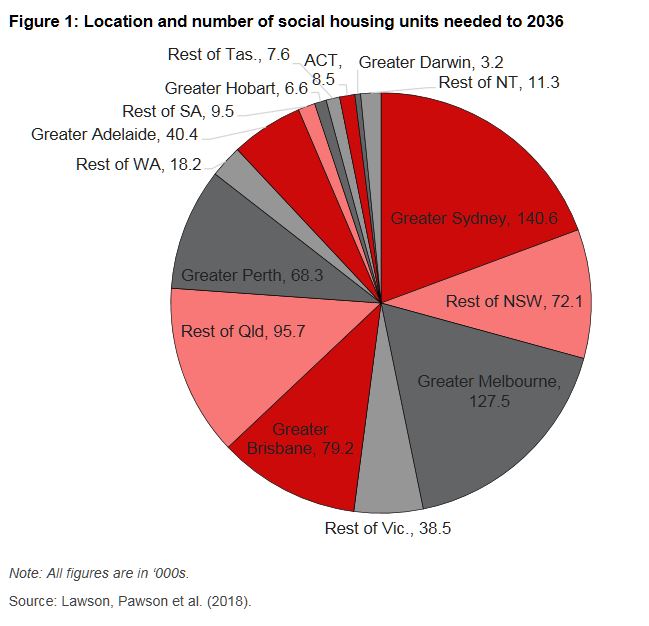

What’s more, the spatial distribution of need for social housing is just as important as the overall volume, as the costs for these dwellings vary from A$146,000 to A$614,000, depending on local land values, building types and construction costs in different regions.

So it’s imperative any public investment program is carefully designed and spatially nuanced.

The AHURI report calls for a new National Housing Authority

The AHURI report also assesses the costs of land and construction needed for social housing, which would underpin a capital investment program.

It calls for the creation of a National Housing Authority to inform, co-ordinate and fund the expansion of new social housing supply through a needs-based capital investment program, together with the existing National Housing Finance Investment Corporation (NHFIC).

In the past, social housing relied on external industry bodies, such as the National Housing Supply Council, to advise on Australia’s future housing needs.

But a national housing authority would provide more effective, consistent and authoritative leadership. It would have the responsibility and resources to plan for and fund more inclusive and sustainable housing outcomes. And it would co-ordinate this effort with other key stakeholders including state Housing Authorities, not for profit community housing providers, the National Disability Insurance Scheme and Clean Energy Finance Corporation.

A net benefit to society

The way cost-benefit assessments are conducted must be changed so the social benefits of social housing are properly quantified. This is necessary not only to capture both productivity and social gains, but also for making a coherent rationale for social housing investment.

But there is more work to be done to improve methods for cost-benefit analysis for social housing, the report says.

In contrast to conventional infrastructure, the housing sector has suffered from a long-term lack of investment. This means the methods for cost-benefit analysis are not yet as advanced.

It’s clear there is no fundamental barrier to government sourced large-scale investment in social housing. An improved cost-benefit analysis method can provide assurance to funding agencies that a long-term social housing construction program is viable and cost effective.

Authors: Julie Lawson, Honorary Associate Professor, Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University; Jago Dodson, Professor of Urban Policy and Director, Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University; Kathleen Flanagan, Research Fellow & Deputy Director, HACRU, University of Tasmania; Keith Jacobs, Professor of Sociology, University of Tasmania; Laurence Troy, Research Fellow, City Futures Research Centre, UNSW; Ryan van den Nouwelant, Lecturer in Urban Management and Planning, Western Sydney University