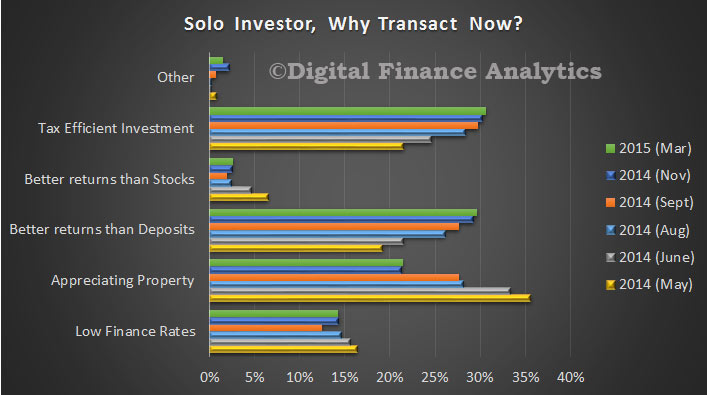

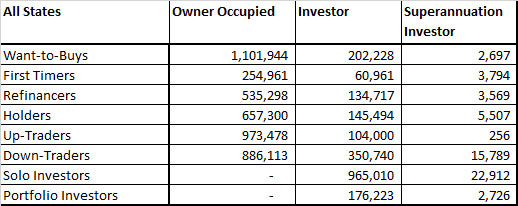

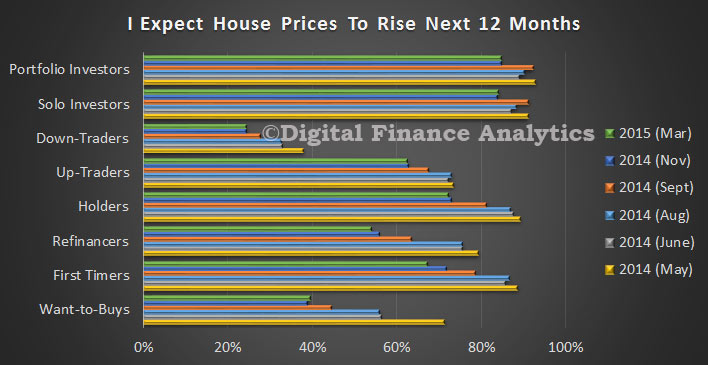

Continuing our series of updates from our latest household surveys, today we look at the latest investment property trends. Looking at solo investors first (using the DFA segmentation) we see the main drivers to transact relate to the continued potential for appreciating property values and the tax efficient nature of the investment. We also see an expectation of higher returns than deposits. This all explains why property investment is so hot. It is, from an investment perspective, for many, the best game in town. The average age for a first time property investor continues to fall, and now stands at 38 years, partly reflecting the rise of first time buyer investors, as we featured recently.

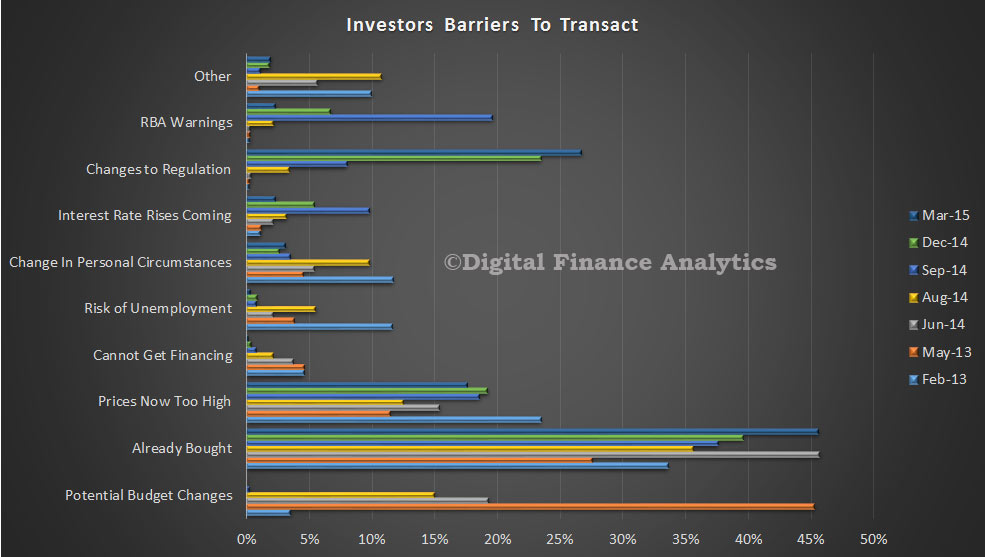

Turning to potential barriers which may stop investors transacting, current prices are not seen as a critical issue – only 18% said this was a turn-off. Whilst 45% had already transacted, there is still significant potential for further purchases, especially in the Sydney and Melbourne markets. We also see that whilst there is some recognition of potential changes to regulation (relating to LVR hurdles, interest only, and gearing), less than one third of investors are worried by this. Finally, only 15% were worrying about potential budget changes, we saw a spike after the budget last year, we may see the same again in our post budget survey. Nearly half expect to select an interest only loan.

Turning to potential barriers which may stop investors transacting, current prices are not seen as a critical issue – only 18% said this was a turn-off. Whilst 45% had already transacted, there is still significant potential for further purchases, especially in the Sydney and Melbourne markets. We also see that whilst there is some recognition of potential changes to regulation (relating to LVR hurdles, interest only, and gearing), less than one third of investors are worried by this. Finally, only 15% were worrying about potential budget changes, we saw a spike after the budget last year, we may see the same again in our post budget survey. Nearly half expect to select an interest only loan.

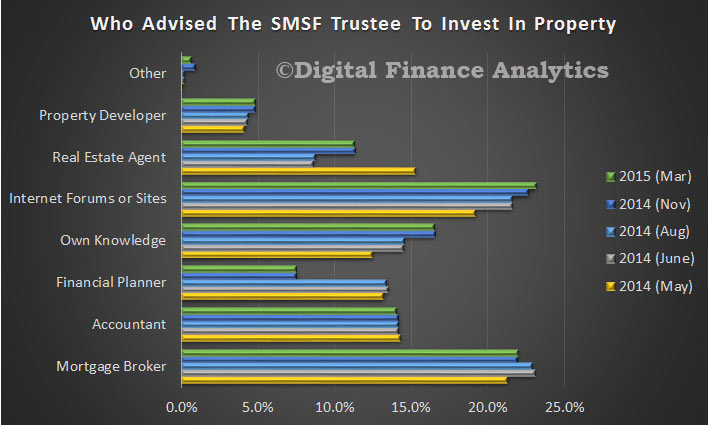

Investing via a super fund is still a minority sport, though some investors are getting advice from internet forums, or mortgage brokers. We estimate about 3.5% of SMSF have an investment property in their fund, and a further 3% are actively considering this investment route.

Investing via a super fund is still a minority sport, though some investors are getting advice from internet forums, or mortgage brokers. We estimate about 3.5% of SMSF have an investment property in their fund, and a further 3% are actively considering this investment route.

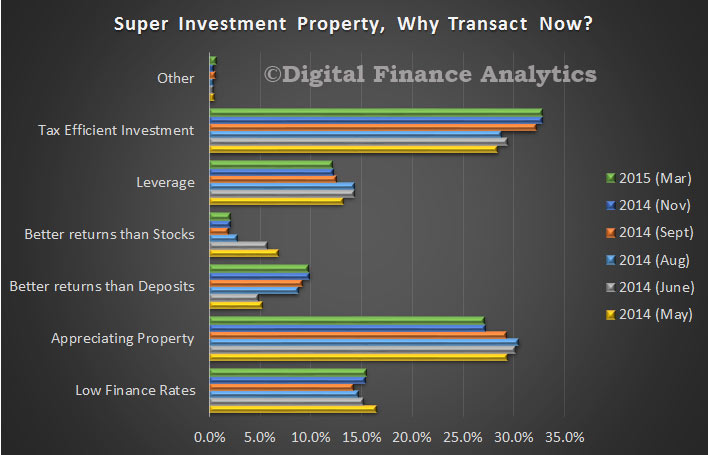

Those who are thinking of a SMSF transaction continue to be attracted by tax efficient outcomes and appreciating property values. These drivers match the broader investment sector quite well as we showed above.

Those who are thinking of a SMSF transaction continue to be attracted by tax efficient outcomes and appreciating property values. These drivers match the broader investment sector quite well as we showed above.

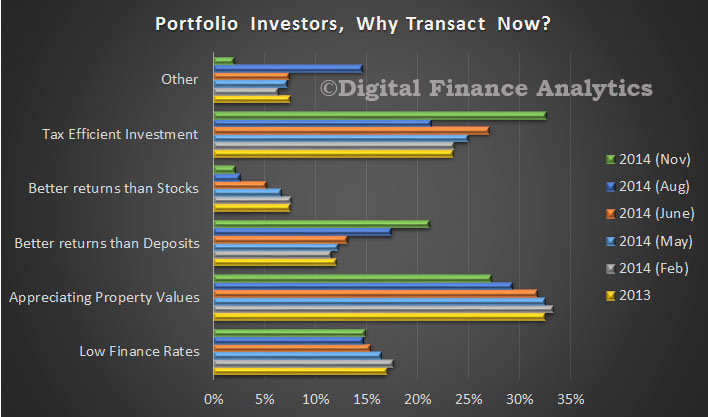

Finally we look at portfolio investors. This is becoming an ever more important sector, because the capital gains and imcone from current properties are being used to leverage further investment, to crease a self-sustaining (some would say critical mass) proposition. The proportion with a holding of 10 properties or more is steadily increasing. Again, these investors are driven by tax efficiency and appreciating property values and also an expectation of better returns than deposits. One trend we detected in this segment is the rise in the number of portfolio investors who now see property investment as their main source of income, it has essentially become their job.

Finally we look at portfolio investors. This is becoming an ever more important sector, because the capital gains and imcone from current properties are being used to leverage further investment, to crease a self-sustaining (some would say critical mass) proposition. The proportion with a holding of 10 properties or more is steadily increasing. Again, these investors are driven by tax efficiency and appreciating property values and also an expectation of better returns than deposits. One trend we detected in this segment is the rise in the number of portfolio investors who now see property investment as their main source of income, it has essentially become their job.

Next time we will look at some of our other segment findings.

Next time we will look at some of our other segment findings.

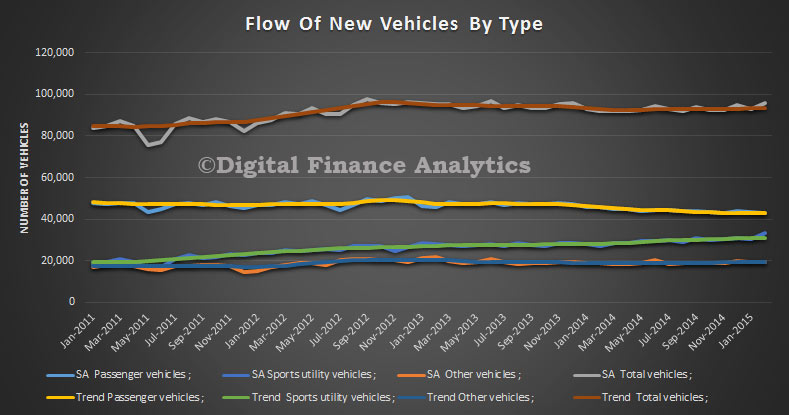

Five of the eight states and territories experienced an increase in new motor vehicle sales when comparing February 2015 with January 2015 in trend terms. Tasmania recorded the largest percentage increase (1.7%), followed by Queensland (0.6%) and both Victoria and South Australia (0.3%). Over the same period, Western Australia, the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory all recorded decreases in sales of 0.3%.

Five of the eight states and territories experienced an increase in new motor vehicle sales when comparing February 2015 with January 2015 in trend terms. Tasmania recorded the largest percentage increase (1.7%), followed by Queensland (0.6%) and both Victoria and South Australia (0.3%). Over the same period, Western Australia, the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory all recorded decreases in sales of 0.3%.