Financial Markets

Members commenced their discussion of financial markets with the observation that central bank policy actions, along with developments in Greece, had been the main focus of markets over the past two months.

Members were briefed about the announcement by the European Central Bank (ECB) of a large sovereign bond purchase program in January, following its assessment that its existing measures would not be sufficient to prevent inflation from remaining well below 2 per cent for a prolonged period. Starting in March, the ECB plans to purchase €60 billion of securities each month, well above the current rate of purchases of private securities; sovereign bonds would be bought in proportion to member countries’ contributions to the ECB’s capital. Debt purchases would continue until there was a sustained increase in inflation, but they would end no earlier than September 2016. This would increase the size of the ECB’s balance sheet past its 2012 peak of €3.1 trillion. While less than the US Federal Reserve’s maximum purchases of US$85 billion a month, on an annualised basis the ECB’s purchases would be equivalent to around 7½ per cent of the euro area’s annual GDP, compared with 6 per cent of US GDP for purchases by the Federal Reserve (and 16 per cent of Japanese GDP for purchases by the Bank of Japan).

Members noted that the Federal Reserve continued to indicate that it expected to start increasing its policy rate around the middle of this year, but financial markets had pushed back expectations for the first rate rise in the United States to around the end of the year. A number of central banks had eased policy in recent months in response to the effect of lower oil prices, including the Reserve Bank of India and the Bank of Canada. Markets had also pushed back expectations for policy tightening by a number of other central banks. In contrast, the central banks of Russia and Brazil had increased their policy rates.

The Swiss National Bank (SNB) abandoned its exchange rate ceiling against the euro, which had been in place since September 2011, and lowered the rate on bank deposits at the SNB by 50 basis points to −0.75 per cent. The SNB’s announcement noted that divergences between the monetary policies of the major currency areas had increased significantly. The move surprised markets, resulting in considerable market volatility and the bankruptcy of several foreign exchange brokers.

Members noted that sovereign bond yields in the major markets had fallen significantly since the December meeting. The falls had occurred across the yield curve but were particularly pronounced at longer maturities, with yields on 10-year bonds in the United States falling back to around 1.6 per cent and those in Germany and Japan reaching historic lows of 30 and 20 basis points, respectively. At these levels there was very little, if any, compensation for term risk. For maturities up to five years, yields on bonds issued by Japan, Germany and most of the core euro area economies, as well as Sweden and Switzerland, had fallen below zero. Yields on Australian government bonds had mostly tracked global developments and had also fallen considerably, with the 10-year yield declining to a historical low below 2½ per cent.

The declines in global bond yields reflected a number of factors but the extent of the decline in yields was difficult to explain. The large bond purchases by major central banks had clearly contributed but so too had a reduction in bond supply, reflecting a narrowing of fiscal deficits in a number of countries. Concerns about the global growth outlook and the risk of sustained low inflation following falls in the oil price had also played a role.

Members noted that the Greek authorities had indicated that they planned to restructure the country’s debt, most of which was owed to official sector institutions. Greece had nonetheless also indicated a desire to remain part of the euro area. The current European assistance program expired at the end of February and markets had been closed to Greece since the recent election. Members also noted that the critical issue in the near term was not so much the obligations of the Greek Government but rather the funding of Greek banks. To date, there had been minimal spillover from developments in Greece to other markets.

There had been sizeable movements in exchange rates since the December meeting, reflecting the increasingly divergent paths of monetary policy among the major advanced economies. Most notably, the Swiss franc had appreciated by around 15 per cent against the euro since mid January. While the US dollar had depreciated against the Swiss franc, it had also appreciated further against most other currencies since the December meeting (including by around 10 per cent against the euro). The renminbi had been little changed against the US dollar over much of 2014, but had depreciated somewhat since the December meeting.

The Australian dollar had depreciated by around 9 per cent against the US dollar since the December meeting. On a trade-weighted basis, the Australian dollar was around 4 per cent below its early 2014 levels, notwithstanding significant falls in commodity prices over the intervening period. The depreciation of the Australian dollar against the US dollar and renminbi had been partly offset by its appreciation against the yen and euro.

Equity prices in advanced economies had been broadly unchanged since early December, notwithstanding a strong rally in European share prices following the announcement of the expansion of the ECB asset purchase program. Global equity prices had risen moderately over 2014, led by an 11 per cent increase in US equity prices, while Chinese equities had significantly outperformed other emerging markets since mid 2014.

In Australia, equity prices recorded a smaller rise over 2014 than that recorded in most global markets, primarily reflecting the decline in equity prices of resource companies. Equity prices had increased by 4 per cent since the start of 2015 even though prices of resource companies had fallen further.

Members noted that Australian lending rates on the outstanding stock of housing and business loans had continued to edge down since the December meeting. At the time of the December meeting, financial market pricing had suggested some chance of an easing in policy during 2015. This expectation strengthened somewhat during January, and by the time of the February meeting pricing reflected a two-thirds probability of a 25 basis point reduction in the cash rate at that meeting, with the cash rate expected to be 2 per cent by the end of the year.

International Economic Conditions

Members noted that growth of Australia’s major trading partners had been around its long-run average in 2014 and that early indications suggested this pace had continued into 2015. Prices of a range of commodities, notably oil and iron ore, had fallen further in recent months, reflecting a combination of both lower growth in global demand for commodities and, more importantly, significant increases in supply. Members also noted that the lower oil prices, if sustained, would be positive for the growth of Australia’s trading partners, which are net importers of energy, and would continue to put downward pressure on global prices of goods and services. Very accommodative global financial conditions were also expected to support global growth in 2015. These positive effects on trading partner growth, however, were expected to be largely offset in 2015 by a gradual decline in the pace of growth in China.

In China, economic growth had eased a little but was close to the authorities’ target for 2014. Growth of household consumption had held up over 2014, while growth of investment and industrial production – which contribute significantly to the demand for commodities – had trended lower over the past year or so. Conditions in the residential property market had remained weak, and measures introduced to support the market appear to have had only a modest effect so far.

In Japan, economic activity had been weaker than expected since the increase in the consumption tax in April 2014, but growth appeared to have resumed in the December quarter and the labour market remained tight. However, inflation had declined in recent months and remained well below the Bank of Japan’s target. The pace of growth had slowed a little in the rest of east Asia over 2014; as the region as a whole is a net importer of oil, activity was likely to have been supported by the decline in oil prices.

Members observed that the US economy had continued to strengthen, resulting in output growing at an above-trend pace over the second half of 2014. Employment growth had picked up further and the unemployment rate had continued to decline. Ongoing strength in the labour market and lower gasoline prices had contributed to a sharp rise in consumer sentiment. On the other hand, growth in the euro area remained modest. Inflation had remained well below the ECB’s target and inflation expectations had declined further, prompting the ECB to implement additional stimulus measures.

Domestic Economic Conditions

Members noted that the data released since the December meeting suggested that the domestic economy had continued to grow at a below-trend pace over the second half of 2014. Resource exports appeared to have continued growing in the December quarter and growth was expected to remain strong, particularly as liquefied natural gas (LNG) production came on line over the next year or so. The lower exchange rate was expected to support growth of exports, particularly service exports such as education and tourism.

Activity and prices in the housing market had continued to be bolstered by the low level of lending rates and strong population growth. A range of indicators, including residential building approvals, suggested further growth of dwelling investment in the near term. Housing price inflation had moderated from the rapid rates seen in late 2013, but remained high and in Sydney and Melbourne had been well above the growth rate of household income. Growth of owner-occupier housing credit had remained around 6 per cent in year-ended terms, while investor credit had continued to grow at a noticeably faster rate.

Members were briefed on the main regulatory actions taken recently to address housing risks in the domestic economy. In particular, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) had announced several policy measures in early December to reinforce sound residential mortgage lending practices. These policies included clarification of prudential expectations on what constituted acceptable growth in housing lending to investors and the possible steps that would be considered if APRA’s expectations were not met, such as increased capital requirements.

Turning to the business sector, members noted that mining investment had continued to decline in the second half of 2014, and larger declines were expected over 2015 as existing projects were completed and very few new projects were likely to proceed. Non-mining business investment had remained subdued and recent data pointed to this continuing into the first half of 2015. Growth in public demand was expected to be subdued over the next year or so.

Members observed that household consumption growth had picked up since its lows in early 2013, supported by low interest rates and rising housing wealth. However, consumption growth had remained below average. The recent decline in fuel prices was expected to provide some offset for overall household incomes from weak growth in labour incomes.

Members noted that the most recent data on the labour market had been a little more positive than early in 2014. However, while employment growth had strengthened somewhat over the past year, the unemployment rate had increased further over 2014 and average hours worked had remained below the levels of a few years ago. Leading indicators of labour demand had changed little in recent months and pointed to only modest employment growth in the months ahead.

Consumer price inflation had declined in year-ended terms, partly as a result of a large fall in fuel prices in the December quarter and the effect of the repeal of the carbon price on utility prices in the September quarter. Various measures of underlying inflation, which largely abstract from these and other temporary factors, had declined in year-ended terms to around 2¼ per cent. Non-tradables inflation (excluding utility prices) had declined further in year-ended terms to relatively low levels, consistent with subdued domestic cost pressures. Prices of tradable items (excluding volatile items and tobacco) were little changed in the December quarter, but were expected to face upward pressure over time from the pass-through of the depreciation of the Australian dollar since early 2013.

Turning their discussion to the economic outlook, members noted that staff forecasts for output, which were conditioned on an assumption of no change in the cash rate, had been revised lower in the near term. Recent data indicated that the expected pick-up in consumption and non-mining business investment was likely to occur later than had been previously anticipated, while the pick-up in LNG exports over coming quarters was now likely to be less rapid. At the same time, it was anticipated that the net effect of commodity price changes and the exchange rate depreciation over the past three months would provide a positive impetus to domestic growth over the next year or so. Overall, the underlying forces driving growth remained much as they had been for some time and GDP growth was still expected to pick up gradually to an above-trend pace in the latter part of the forecast period.

The revisions to GDP growth implied that the unemployment rate would peak at a higher rate and later than had been previously forecast, before declining gradually. The inflation forecast had also been revised lower, reflecting the softer outlook for labour and product markets as well as the recent fall in oil prices. Headline inflation was expected to remain low for a time, before picking up at the end of the forecast period. Underlying inflation was expected to remain well contained and consistent with the target throughout the forecast period.

Members discussed a number of uncertainties around the forecasts. They noted that developments in commodity markets, particularly the price of oil, would affect future global growth and inflation outcomes. One area of uncertainty continued to be the outlook for the Chinese property market and its implications for Chinese demand for commodities. Members also noted that developments in commodity markets were likely to be affected by supply factors; for instance, the response of ‘unconventional’ oil producers in North America to lower oil prices.

As usual, the path of the exchange rate remained a key area of uncertainty. Members noted that the exchange rate had remained above most estimates of its fundamental value, given the decline in commodity prices over the past year, and that future exchange rate movements would be affected by market expectations for monetary policy, both domestically and abroad. They noted that, all else being equal, a sustained further depreciation would, if it occurred, stimulate growth in the domestic economy and put some temporary upward pressure on inflation.

Members noted that there was considerable uncertainty around the timing and extent of the expected increase in household consumption growth and non-mining business investment. Although fundamental factors such as low interest rates and strong population growth remained in place, they had not been sufficient to see a significant pick-up in the growth of these variables or a decline in the degree of spare capacity in the labour market. In addition, recent data suggested that the expected improvement in economic conditions would occur later than had been previously expected. Members commented that a strengthening in non-mining investment was a necessary element for growth to pick up to an above-trend pace, and noted the importance of confidence in underpinning such an outcome. Indeed, an improvement in the appetite for businesses to take on risk had the potential, should it occur, to lead to much stronger growth in non-mining business investment than currently forecast.

Considerations for Monetary Policy

In assessing the appropriate stance for monetary policy in Australia, members noted that the outlook for global economic growth was little changed, with Australia’s major trading partners still forecast to grow by around the pace of recent years in 2015. Commodity prices, particularly those for iron ore and oil, had declined over the past year largely in response to expansions in global supply, though members judged that demand-side factors, such as the weakness in Chinese property markets, had also played some role. Conditions in global financial markets had remained very accommodative.

Domestically, over recent months there had been fewer indications of a near-term strengthening in growth than previous forecasts would have implied. This included survey measures of household and business confidence, which remained around or even a bit below average. As a result, the revised staff forecasts – which were based on an unchanged cash rate – suggested that GDP growth would remain below trend over the course of this year, before gradually picking up to an above-trend pace in 2016, somewhat later than had been previously expected. The unemployment rate was therefore expected to peak a little higher (and later) than in the previous forecast. The net effect of declining commodity prices and the depreciation of the exchange rate was expected to boost growth over the forecast period. Nonetheless, the higher degree of spare capacity now in prospect and lower oil prices had led to a lowering of the forecast for inflation, offset somewhat by the effects of the recent exchange rate depreciation. The restrained pace of wage increases over the past year or so and accompanying growth in productivity, which had dampened growth in unit labour costs, suggested that low rates of inflation were likely to be sustained. In other respects, the forces underpinning the outlook for domestic activity and inflation were much as they had been for some time.

Members noted the current accommodative setting of monetary policy, which had been providing support to domestic demand. They noted that the Australian dollar had depreciated noticeably against a rising US dollar over recent months, although less so against a basket of currencies, and that it remained above most estimates of its fundamental value, particularly given the significant declines in key commodity prices. Members agreed that a lower exchange rate was likely to be needed to achieve balanced growth in the economy.

Given the large increases in housing prices in some cities and ongoing strength in lending to investors in housing assets, members also agreed that developments in the housing market would bear careful monitoring. They noted that it would be important to assess the effects of the measures designed to reinforce sound residential mortgage lending practices announced by APRA in December.

On the basis of their assessment of current conditions and taking into account the revised forecasts, the Board judged that a further reduction in the cash rate would be appropriate to provide additional support to demand, while inflation outcomes were expected to remain consistent with the 2 to 3 per cent target. In deciding the timing of such a change, members assessed arguments for acting at this meeting or at the following meeting. On balance, they judged that moving at this meeting, which offered the opportunity of early additional communication in the forthcoming Statement on Monetary Policy, was the preferred course.

The Decision

The Board decided to lower the cash rate by 25 basis points to 2.25 per cent, effective 4 February 2015.

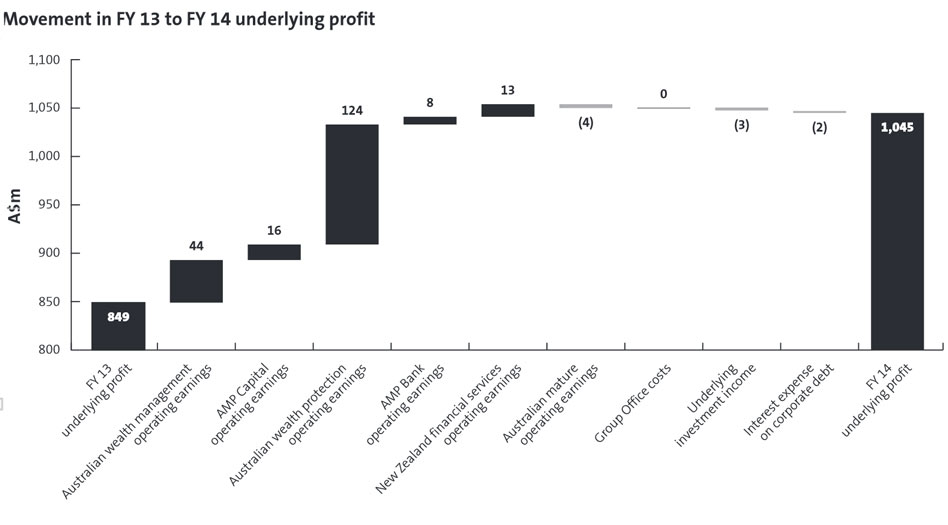

The Board has declared a 17 per cent increase to the final dividend to 13.5 cents per share compared with 11.5 cents per share for the 2013 final dividend. This represents a FY 14 payout ratio of 74 per cent of underlying profit and is within AMP’s target range of paying 70 to 80 per cent of underlying profit.

The Board has declared a 17 per cent increase to the final dividend to 13.5 cents per share compared with 11.5 cents per share for the 2013 final dividend. This represents a FY 14 payout ratio of 74 per cent of underlying profit and is within AMP’s target range of paying 70 to 80 per cent of underlying profit.