RBA Assistant Governor (Economic) Luci Ellis spoke at the ABE Conference “Three Questions About the Outlook“.

The section on the impact of weak income growth is significant, because it examines why households are under financial pressure, and the impact of this. She says “continued weak income growth presents a particular risk to the consumption outlook in the context of high household indebtedness”.

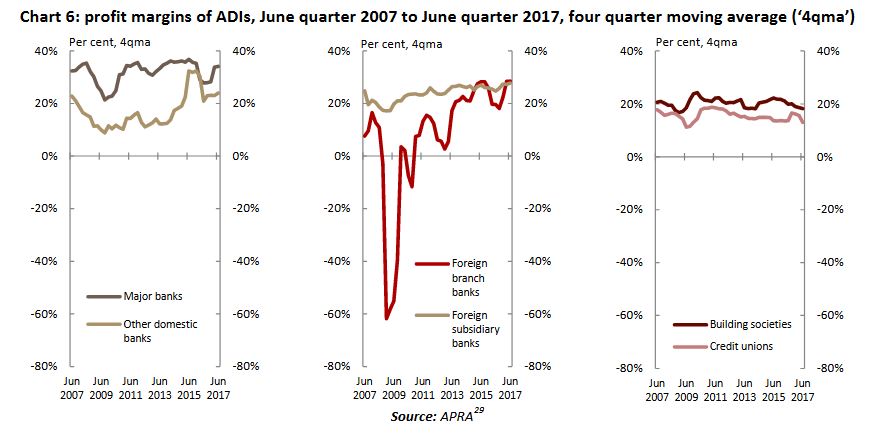

One aspect of recent developments where Australia’s experience differs, though, relates to household income and consumption. As we discussed in the Statement, consumption growth in the major advanced economies has been quite robust, supported by strong growth in employment. In Australia, we’ve also had especially strong employment growth over the past year – more than double the rate of growth in the working-age population. But that hasn’t translated into strong consumption growth. Household income growth has been weak for a number of years, and that has weighed on consumption growth (Graph 4). Consumption growth hasn’t slowed as much as income growth. This is what you’d expect, given that households generally try to smooth their consumption through episodes of income volatility. But there’s a real question of how long that could continue if income growth stays weak. This clearly has implications for how we think about the risks to our consumption forecasts.

The weakness in incomes goes beyond the downward pressure on wage growth that I’ve already spoken about. Yes, growth in the wage price index (WPI) has stepped down. But the WPI captures a fixed pool of jobs. It abstracts from compositional change. Average earnings as measured in the national accounts have been even weaker than the WPI (Graph 5). This has not occurred because workers shifted between industries; it is also seen within industries. It might be partly driven by the end of the mining investment boom, as workers moved out of mining-related work, including in the construction and business services industries. But it seems to have been broader than that. Our central forecast is that this weakness will end as the drag from the end of the boom dissipates and spare capacity is absorbed, such that average earnings growth recovers. There is no guarantee of this, though, and therein lies the risk.

The living cost pressures that many households feel have therefore been an income story, not a price inflation story. Although utilities prices did increase significantly in some states in recent quarters, much of households’ regular spending has seen relatively little in the way of price increases for a number of years.

Weak income growth can run below consumption growth for a time, but not forever. If households start to see this weakness in income growth as permanent, they are likely to change their spending patterns in response. We might be seeing this in the details of the consumption figures: growth in spending on discretionary items, like travel and eating out, has slowed while growth in spending on essentials has held up (Graph 6).

Continued weak income growth presents a particular risk to the consumption outlook in the context of high household indebtedness. Households do not just wake up one day and collectively decide to pay down their debt. But if incomes turn out weaker than they expect, or some other adverse news should arise, the households carrying the most debt might feel they have to rein in their spending quite a bit.