A newly released IMF working paper ” Does Prolonged Monetary Policy Easing Increase Financial Vulnerability?” looks at how banks behave in an easing monetary policy environment. They found that the leverage ratio, as well as other measures of firm-level vulnerability, increases for banks and nonbanks as domestic monetary policy easing persists. Cross-border effects are also notable. Results are non-linear, with risk-taking behavior rising most quickly at the onset of monetary policy easing.

We think think this means that in a low interest rate environment, counter-cyclical buffers should be increased. In Australia, in the current low rate environment, policy settings are still too generous.

While decisive and persistent monetary policy accommodation was necessary to support aggregate demand in advanced economies during and after the financial crisis, there is lingering concern about the side effects of low interest rates and central bank balance sheet expansion on risk-taking behavior in the financial sector. In this paper, we investigate the extent to which financial vulnerabilities build up at the firm level during extended periods of monetary policy easing at home and in the U.S.

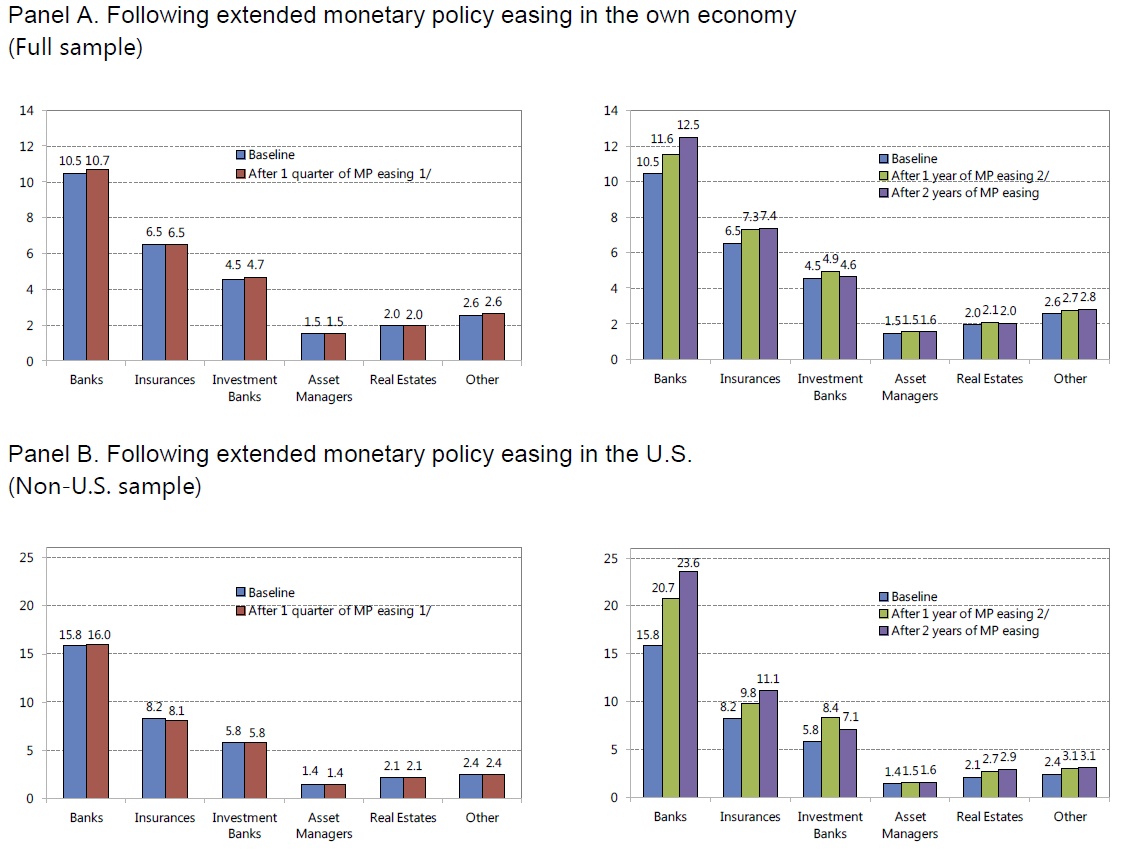

Based on a data for roughly 1,000 bank and nonbank financial institutions—including insurance companies, investment banks and asset managers—in 22 countries over the past 15 years, we find significant evidence of increased risk-taking behavior. Domestic banks and nonbanks alike increase their leverage ratios in response to persistent monetary policy accommodation at home. In addition, prolonged Federal Reserve policy easing leads banks and nonbanks outside the U.S. to take on more risks, with an effect similar to equivalent domestic monetary policies.

These results are robust to alternative measures of financial vulnerability, controls, and specifications. Importantly, the relationship between persistent monetary policy easing and financial firm vulnerability appears to be non-linear, with risk-taking behavior rising most quickly at the onset of policy easing.Our findings ideally will spur research in two directions. First, further work is needed to develop benchmarks for risk-taking behavior. While we document an increase in risks taken by financial institutions, we are unable to take a position on whether such increases in risk are worrisome or excessive. Some degree of change in risk-taking is an inherent part of the monetary policy transmission mechanisms. To some extent, if prudential policies and regulations inhibit financial institutions from taking more risk in response to monetary policy easing, the expansionary effect of monetary policy on the real economy may be diminished.

Second, our results should inform the ongoing debate on using monetary policy tightening for financial stability purposes (see IMF, 2015, for instance). Costs of doing so would arise from lower employment and output in the short to medium run, feeding back to higher defaults and funding costs, thus reducing financial stability. But benefits need further exploration. The emphasis so far has been on the link between policy rates and credit growth, and in turn between credit growth and financial stability (Svensson, 2015). However, this paper suggests that the link could also go through the leverage of financial sector firms.

But even without further work, our results have several policy implications. Countries should closely monitor financial sector risks during periods of monetary policy accommodation at home, and in the U.S. They should develop solid prudential and regulatory frameworks, so as to preserve room for monetary policy to manoeuver to achieve its inflation and output objectives. Such frameworks should apply to both banks and nonbanks.

Note: IMF Working Papers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to encourage debate. The views expressed in IMF Working Papers are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.