According to the South China Morning Post, cash-rich Chinese firms – the big spenders in the global property market in the past four years – are getting cold feet as Beijing tightens controls on outbound investment.

“Requests for overseas acquisitions are already drying up,” said Paul Guan, a partner with global law firm Paul Hastings who advises Chinese institutional investors on overseas real estate.

“Business owners all know the Chinese government has sent a clear signal this time that they want to curb overseas investment in the property sector,” Guan said.

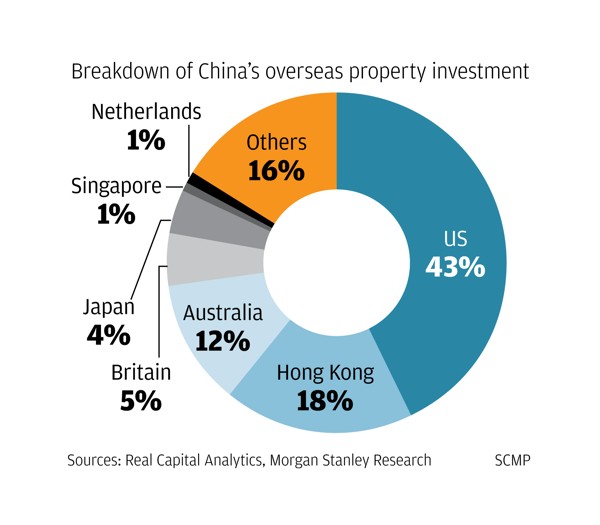

The move will put pressure on prices in key property markets from New York to London. The top three overseas destinations for Chinese property investors in 2016 were the United States, Hong Kong and Australia, while pending deals have accumulated mainly in Britain and the US over the past six months, according to Real Capital Analytics.

Chinese were the biggest foreign investors in US and Australian real estate last year, accounting for 25 per cent of deals in the US and 26 per cent in Australia.

They also accounted for 25 per cent of all central London commercial property acquisitions in 2016, while some 80 per cent of residential land sold in Hong Kong so far this year was bought by Chinese firms, according to data from Morgan Stanley. Chinese investment in the city has quadrupled since 2012, the financial services firm said.

“Transaction volumes will definitely go down in the hot destinations, and property prices could also be affected,” said Hans Kang, chief investment officer of InfraRed NF Investment Advisers.

On Friday, the State Council said it would restrict overseas investment in a number of areas including property, hotels, the film industry and other forms of entertainment, and sports clubs. Investors would have to seek special approval from the regulators for such ventures.

Dalian Wanda Group on Tuesday backed away from a £470 million (US$605.63 million) acquisition of the Nine Elms Square site in London, after the government’s new capital controls were announced.

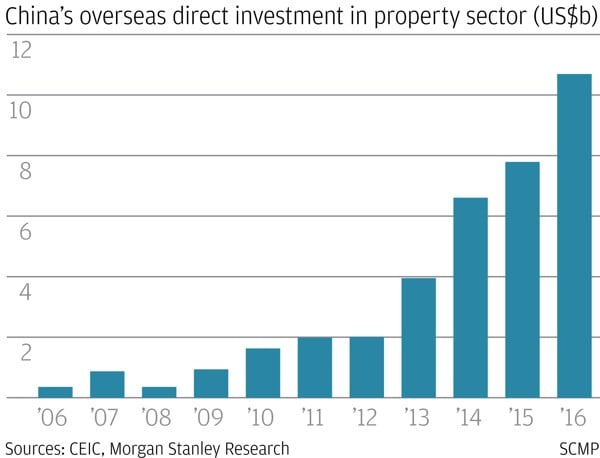

Outbound investment by Chinese companies has surged since 2013, with Beijing pushing for more of them to go global and as foreign exchange reserves continued to pile up.

But the government has since 2015 become worried about the scale of capital outflows, particularly in property, at a time when the yuan has sharply depreciated and there are fears of a domestic property bubble, creating problems for the country’s balance of payments.

Added to those fears are companies that borrow money on mainland China to buy overpriced overseas assets, which runs counter to President Xi Jinping’s deleveraging efforts.

“That could hit the financial stability of China’s banking system if there are any fluctuations in outside markets,” Kang said.

“Chinese buyers accounted for 25 per cent of all central London commercial property acquisitions in 2016, according to Morgan Stanley.In past months, policymakers have tightened regulations on “irrational overseas investment” and ordered banks to check the credit exposure of a number of aggressive dealmakers including Wanda, Fosun International, HNA Group and Anbang Insurance Group.

All of those companies had been on a shopping spree in overseas property markets in recent years.

Anbang, for example, made headlines in 2014 with its US$2 billion purchase of New York’s Waldorf Astoria hotel.

HNA Group, which owns Hainan Airlines, meanwhile bought a 25 per cent stake in Hilton Worldwide Holdings for US$6.5 billion last year. It has also paid a record HK$27.2 billion for four residential sites in Hong Kong since November.

And Wang Jianlin, who runs one of China’s biggest property developers, Wanda, has invested some A$2 billion (US$1.58 billion) in two mega mixed-use projects in Australia since 2014.

Wang Jianlin, who runs Wanda, has invested US$1.58 billion in two mega mixed-use projects in Australia since 2014.

But now those dealmakers find themselves under intense government scrutiny, their ambitious global plans have come to a screeching halt and their focus is shifting back to the domestic market.

Wang told financial media outlet Caixin last month that his company would “actively respond to the state’s call and divert its main investments to China” after it sold off US$9.3 billion of assets to rivals in order to repay debts.

The retreat is already being felt in global markets. Outbound property investment by mainland Chinese firms was down 82 per cent in the first half from a year ago – and it’s expected to plummet 84 per cent for the whole year to US$1.7 billion, according to Morgan Stanley. The total investment in 2016 was US$10.6 billion.

That trend will create headwinds for prices in Hong Kong, the US, Britain and Australia over the medium term – especially for office assets in Manhattan, central London and Hong Kong, which is the most exposed, it said.

Guan from the law firm said prices in the high-end residential market in New York were also likely to be hit by the loss of Chinese buyers.

For the first time since October 2012, no contracts worth over US$10 million were signed in the city last week, according to data from Olshan Realty.

Others were more positive, and believed the impact of the restrictions would be limited to related markets, which would continue to be shaped by broader macroeconomic trends and fundamentals.

“Fortunately, the United States’ key markets are still desirable enough that without one particular flow of capital from a region, the impact should be nominal if all economic and market conditions are normal and healthy,” said Andrew Feldman of New York-based real estate agency Triplemint.

Added to that, many Chinese companies had already moved currency overseas and could continue to issue debt or equity through offshore platforms if they wanted to invest in property, according to Ben Briggs, executive vice-president of Briggs Freeman Sotheby’s International Realty based in Xiamen.

“They will just do the investments in a more quiet and sophisticated way,” Briggs said.

Thomas Lam, senior director of Knight Frank, agreed that the restrictions would not stop Chinese companies from investing abroad.

“In the longer term, going global will continue and it will remain an essential means for Chinese companies to diversify risks and secure sustainable returns,” Lam said.