The latest edition of our weekly finance and property news digest with a distinctively Australian flavour.

Category: Banking Culture

APRA Goes Back To The Future On Bank Capital

ANZ Complies With ASIC Court Enforceable Undertaking

Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (ANZ) has complied with the Court Enforceable Undertaking (CEU) entered into with ASIC in March 2018 regarding ANZ’s fees for no service conduct for its Prime Access service.

On 31 May 2019, ASIC received an audited attestation from ANZ signed by Mr Michael Norfolk, Managing Director Private Banking and Advice, and an independent expert report from Ernst & Young (EY).

ASIC is satisfied with the audited attestation and the independent expert report. Compliance with the obligations under the CEU is now finalised, save for the payment of some remaining refunds due to clients, to be completed by mid-July 2019.

ANZ has attested to the following as required under the CEU:

- the changes to ANZ’s systems, controls and processes that have been implemented in response to the fees for no service conduct;

- subject to (c), that ANZ has provided documented annual reviews to Prime Access customers who were entitled to such reviews in the period from January 2014 to March 2018;

- in the 1,410 instances where documented annual reviews were found to have not been provided, ANZ is in the process of refunding those customers (with remediation expected to be complete by mid-July 2019); and

- that ANZ now has systems, controls and processes that seek to ensure documented annual reviews are being provided, and that instances of non-delivery are detected and remediated.

ASIC is aware that ANZ has announced it will no longer offer the Prime Access service to new customers and will phase it out for current customers over the next 18 months. ASIC will monitor the phasing out of Prime Access.

APRA Imposes Conditions on AMP Super

APRA says it has issued directions and additional licence conditions to AMP Superannuation Limited and N.M. Superannuation Proprietary Limited (collectively AMP Super).

APRA has imposed the directions and additional licence conditions to address a range of concerns regarding AMP Super’s compliance with the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (SIS Act). The action arises from issues identified during APRA’s ongoing prudential supervision of AMP Super, along with matters that emerged during the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry.

The new directions and conditions are designed to deliver enhanced member outcomes by requiring AMP Super to make significant changes to its business practices. Areas identified for improvement include conflicts of interest management, governance and risk management practices, breach remediation processes, addressing poor risk culture and strengthening accountability mechanisms. The directions also require AMP Super to renew and strengthen its board.

Additionally, APRA requires AMP Super to engage an external expert to report on remediation and compliance with the new directions and conditions.

This is the second time APRA has used the broader directions power that was granted in April following the passage of the Treasury Laws Amendment (Improving Accountability and Member Outcomes in Superannuation Measures No 1) Bill 2019. It also demonstrates APRA’s commitment to embedding the “constructively tough” enforcement appetite outlined in April’s new Enforcement Approach

The RBA’s Marching Orders No Longer Realistic?

A somewhat obscure fact about the marching orders for Australia’s Reserve Bank is that, usually, when a government is elected or re-elected or a new governor takes office, the official agreement between the government and the Reserve Bank changes.

There have been seven such agreements so far, each signed by the federal treasurer and bank governor of the time, and each entitled “Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy”.

The first was signed by treasurer Peter Costello and incoming governor Ian Macfarlane in 1996, the second when Costello reappointed Macfarlane in 2003, and the third when Costello appointed Glenn Stevens in 2006.

The fourth was between new treasurer Wayne Swan and Stevens on Labor’s election in 2007, and the fifth between Swan and Stevens on Labor’s reelection in 2010.

The sixth was between incoming treasurer Joe Hockey and Stevens on the Coaition’s election in 2013, and the most recent one between treasurer Scott Morrison and incoming governor Philip Lowe in 2016.

The current agreement begins this way:

The Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy (the Statement) has recorded the common understanding of the Governor, as Chair of the Reserve Bank Board, and the Government on key aspects of Australia’s monetary and central banking policy framework since 1996.

For nearly a quarter of a century, as the statement goes on to note, there has been a core component of how monetary policy is conducted:

The centrepiece of the Statement is the inflation targeting framework, which has formed the basis of Australia’s monetary policy framework since the early 1990s.

But over the years, there have been tweaks. One was this change between the 2013 and 2016 statements.

2013:

Low inflation assists business and households in making sound investment decisions…

2016:

Effective management of inflation to provide greater certainty and to guide expectations assists businesses and households in making sound investment decisions…

The change from “low inflation” to “effective management of inflation” sounds subtle, but was no accident. It gave the Reserve Bank extra wiggle room around the inflation target.

And boy, did it come in handy.

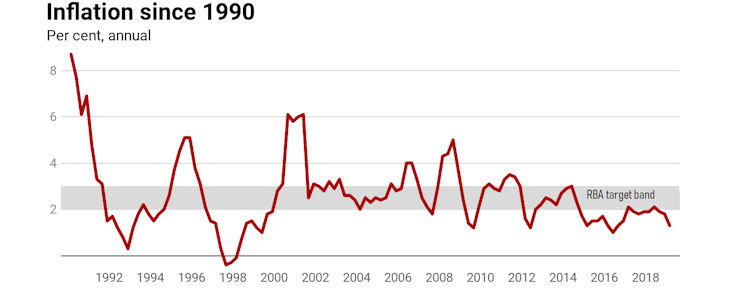

The target that’s rarely met

The big question about the agreement is whether the next one (between Frydenberg and Lowe on the Coalition’s reelection) will tweak the target again, change it completely, or do something in between.

Because it presumably can’t remain the same.

One reason to think it will change, perhaps significantly, is the bank’s utter inability to even get particularly close to its target inflation band of 2-3%, let alone to get within tit, “on average, over time” as required by the agreement.

You might not think this matters too much. But it does.

The inflation target is crucial in setting stable expectations for consumers, businesses and markets.

Don’t just take my word for it.

Here is what the previous Reserve Bank governor, Glenn Stevens, said in his last official speech before handing over to Philip Lowe in August 2016:

From 1993 to 2016, a period of 23 years, the average rate of inflation has been 2.5% – as measured by the CPI, and adjusting for the introduction of the goods and services tax in 2000. When we began to articulate the target in the early 1990s and talked about achieving “2–3%, on average, over the cycle”, this is the sort of thing we meant. I recall very well how much scepticism we encountered at the time. But the objective has been delivered.

As I pointed out last month, expectations about price movements depend on Australians believing that the bank will do what it says it will do.

Once people lose faith in the bank’s commitment to or ability to achieve the target, inflation expectations become unmoored. People react to what they think what might happen rather than what they are told will happen. This is what led to Australia’s wage-price spirals in the 1970s and 1980s, and to Japan’s lost decades of deflation.

Three possible outcomes

One possibility is the same statement, word for word. It would be meant to signal that the bank and the government think things are under control.

A second possibility is a tweak that further emphasises the “flexible” nature of the target, along the lines Lowe mentioned in his speech at this month’s Reserve Bank board board dinner in Sydney. It would provide more cover for the bank’s inability to hit its target.

A third option would be to add some discussion of the importance of fiscal policy – government spending and tax policy – as a complement to the Reserve Bank’s work on monetary policy. Lowe is keen to mention that he is keen on it, every chance he gets.

But that would put the government under implicit pressure to run budget deficits at times like those we are in rather than surpluses. It’s hard to see the Morrison government signing up for that, given its repeated talk during the election about the importance of being “responsible”.

Or something more

At the more radical end of the spectrum would be a genuinely new framework for monetary policy.

In the United States, which has also missed its inflation target, though by not as much as Australia, there has been much discussion of moving to a “nominal GDP target”. The range mentioned is 5-6% a year.

Advocates of this include former US Treasury secretary Larry Summers, who outlined his rationale in a Brookings Institution report in mid-2018.

ANU economist and former Reserve Bank board member Warwick McKibbin championed the idea along with economists John Quiggin, Danny Price and then Senator Nick Xenophon in the leadup to the 2016 agreement between Morrison and Lowe.

Nominal GDP is gross domestic product before adjustment for prices. In countries subject to big changes in export prices such as Australia, it can provide a better guide to changes in income.

When nominal GDP is strong (as it is when minerals prices are high) consumer spending is likely to be strong – perhaps too strong. When it is weak (as it is when minerals prices collapse) consumer spending is likely to be weak and in need of support.

But don’t get your hopes up

Given the natural caution of the bank and of this government, we should probably expect something at the modest end of the spectrum – even if something like a nominal GDP target would make sense.

Perhaps what’s most important isn’t what the statement says, but that it says something and that the Reserve Bank sticks to it. It will lose an awful lot of credibility if it sticks to nothing.

In the words of Nobel Laureate Bob Dylan: “they may call you doctor, they may call you chief, but you’re gonna have to serve somebody … it may be the devil or it may be the Lord, but you’re gonna have to serve somebody.”

Author: Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW

CBA Sells Count Financial; Holds $200m Indemnity Risks

CBA has today entered into an agreement to sell Count Financial Limited to ASX-listed CountPlus Limited.

Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA) has today entered into an agreement to sell Count Financial Limited (Count Financial) to ASX-listed CountPlus Limited (CountPlus) for $2.5 million (the Transaction). CountPlus is a logical owner of Count Financial given its historical corporate relationship and equity holdings in 15 Count Financial member firms.

CBA will continue to support and manage customer remediation matters arising from past issues at Count Financial, including after completion of the Transaction. CBA will provide an indemnity to CountPlus of $200 million and all claims under the indemnity must be notified to CBA within 4 years of completion. This indemnity amount represents a potential contingent liability of $56 million in excess of the previously disclosed customer remediation provisions that CBA has made in relation to Count Financial of $144 million (which formed part of the remediation provisions announced in the 3Q19 Trading Update). CBA has already provided for the program costs associated with these remediation activities.

The Transaction is subject to a CountPlus shareholder vote to be held in August 2019 and completion is expected to occur in October 2019. The Transaction is not expected to have a material impact on the Group’s net profit after tax.

CBA currently owns a 35.9% shareholding in CountPlus and intends, subject to market conditions, to sell its shareholding in an orderly manner over time following completion of the Transaction.

From a financial perspective, the Transaction will result in CBA exiting a business that, in FY19, is estimated to incur a post-tax loss of approximately $13 million.

Implications for NewCo

Following completion of the Transaction, NewCo will comprise Colonial First State, Financial Wisdom, Aussie Home Loans and CBA’s 16% stake in Mortgage Choice. Consistent with the announcement in March 2019, CBA remains committed to the exit of these businesses over time. The current focus is on continuing to implement the recommendations from the Royal Commission and ensuring CBA puts things right by its customers.

An Insider Speaks To The People

Here is an extended discussion between Ex APRA/ASIC Executive Wilson N. Sy, Economist John Adams and Analyst Martin North. We look at how banking is regulated and who is really pulling the strings.

Can Frazis Turn BOQ’s Fortunes Around?

After successfully leading Westpac’s consumer bank, BOQ’s new boss George Frazis has landed a big job at a much smaller bank with a shrinking mortgage book, via InvestorDaily.

In April, Bank of Queensland reported reporting negative mortgage growth of $248 million, down from positive growth of $11 million in 1H18, with its portfolio dropping to $24.7 billion.

The fall was driven by a $717 million contraction in settlements through BOQ’s retail bank, offset by a $469 million rise in home loan volumes through its subsidiary, Virgin Money Home Loans.

The regional lender is well aware of the challenges within its retail bank, which is effectively franchised with branches being run by ‘owner-managers’. Given the negative press generated by the royal commission, attracting new owner managers has been difficult for BOQ.

Prior to the appointment of George Frazis as CEO on 6 June, interim chief executive Anthony Rose delivered an 8 per cent drop in cash earnings in the first half of FY19.

“Across the industry, as you are well aware, there have been significant changes in the banking landscape which has created revenue headwinds for the sector. In addition, the outcome from the royal commission is lifting expectations of the regulators. Adjusting to the new regulatory environment will come with a higher cost profile, absent any mitigating actions which we are of course exploring,” Mr Rose said in April.

“BOQ also has challenges that are specific to our business, particularly in the retail bank. Our digital customer offering, lending processes and the inability to attract new owner-managers with the overlay of regulatory uncertainty, has hampered customer acquisition and returns.”

Mr Rose, BOQ’s chief operating officer, will remain as interim CEO until Mr Frazis takes over in September. Rose took charge following the resignation of John Sutton in December 2018.

Morningstar analyst David Ellis praised the appointment of Mr Frazis, an experienced banker with 17 years in the industry, most recently as CEO of Westpac’s consumer bank and CEO at St George Bank.

“While Frazis has strong credentials and deeply understands the dynamics of Australia’s consumer banking industry, he will be taking control of a regional player with a small geographic distribution footprint, higher funding and operational costs, a lower credit rating and tougher regulatory capital burden,” Mr Ellis said.

The Morningstar analyst believes the challenge for Mr Frazis is to assume a bigger role in a smaller organisation that lacks market share, brand awareness, distribution capabilities and funding advantages that major banks enjoy.

“Bank of Queensland’s lending growth has been subdued for several years,” Mr Ellis said. “Based on APRA banking statistics for April 2019, the bank’s 12-month growth in home loans sit at just 0.3 per cent in April, compared to 1.7 per cent a year ago and 11.8 per cent three years prior.”

Bank system home loan growth is 3.3 per cent for the year to April 2019.

With the RBA cutting rates this month, BOQ has lowered its fixed rates in an effort to remain competitive in a mortgage market dominated by the big four. However, with more cash rate cuts expected, Morningstar is concerned whether BOQ can sustain its course of passing on the reductions.

“The bank lacks access to lower-cost funding options and has a much lower return on equity than the major banks,” Mr Ellis said.

Under Mr Frazis’ leadership, Westpac’s consumer bank attracted more than a million new customers in the past four years. Digital channels now account for a third of sales.

“Frazis will have to do the same at Bank of Queensland,” Mr Ellis said

Bail-In Mark 2

I discuss the latest attempt to deal with deposit bail-in with Robbie Barwick from the CEC, who have just launched a new petition seeking to exclude bank deposits.

Visionary RBNZ Shows Up RBA

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand has released an important statement on the new approach they are going to adopt in policy setting. The focus will be on improving wellbeing. In addition they are expanding their dna to avoid group think. This follows their recent moves to lift bank capital.

There is so much here the RBA should embrace.

The Reserve Bank has significantly changed the way it makes monetary policy decisions, keeping itself in step with public expectations.

In a panel discussion last week at the Institute for Monetary and Economic Studies (Bank of Japan) in Tokyo, Reserve Bank Assistant Governor and General Manager of Economics, Financial Markets and Banking Christian Hawkesby talked about the importance of good decision making and governance, and of being credible and trusted, in achieving the long-term goal of improving wellbeing.

“We maintain our legitimacy as an institution by serving the public interest and fulfilling our social obligations. Keeping our ‘social licence’ to operate depends on maintaining the public’s trust that we are improving wellbeing,” Mr Hawkesby said.

“Thirty years ago New Zealand was prepared to accept a single expert – the Governor – making decisions about how to fight inflation. People now expect to see how and why decisions are made, expect that decision makers reflect wider society, and that current issues and concerns are factored into the decision making. By meeting these expectations, we can improve public trust in the legitimacy of the Reserve Bank’s work,” he said.

Mr Hawkesby outlined the new committee process that the Reserve Bank uses for deciding the official cash rate, noting that diversity among decision makers improves the pool of knowledge, insures against extreme views, and reduces groupthink.

“This diversity is needed to confront issues such as climate, technological, and other structural and social changes,” he said.

He also said that collaboration with government can be undertaken in a way that maintains the Reserve Bank’s political independence while working on the broader objective of improving wellbeing.

Here is the supporting speech.

Introduction

Tena koutou katoa

Thank you for the opportunity to talk about the Reserve Bank of New Zealand and the changes we are making to maintain our credibility in times of change.

I would like to focus on two building blocks of credibility:

- renewing a social licence to operate by aligning our objectives with the needs of the public; and

- achieving those objectives through good decision making enabled by a framework of good governance.

A common theme is the importance of transparency.

The imperative for change: Central banks in the 21st century

The first building block of credibility is the renewal of a social licence to operate—by this I mean the legitimacy an institution earns by serving the public interest. It is granted by the public when an institution is seen to fulfil its social obligations.1

New Zealand was the first country to officially adopt inflation targeting in 1989, with a number of central banks around the world following the example.2 Under a single-decision-maker model, we brought inflation down from around twenty percent to two percent in five years. In doing so, we helped build our credibility during the high-inflation environment of the times.3

Fast-forward to 2019, and monetary policy in New Zealand has undergone major change. Firstly, we have adopted a dual mandate, focused on achieving price stability and supporting maximum sustainable employment. Secondly, we have adopted a committee structure for decision making, and are delivering greater transparency in our decision making.

Why the change?

The reform of our framework was not merely a simple choice based on technical performance. As you can see in figure 1, when it comes to inflation and growth, over the past 30 years inflation-targeting central banks (e.g. New Zealand and the United Kingdom) have a pretty similar track record to central banks with a dual mandate (e.g. Australia and the United States). 4

The imperative for change comes from more than examining our history; it comes from our expectations of the future, and the present we find ourselves in. Our policy framework changed because times are changing. For the Reserve Bank to maintain its credibility and relevance, we must change too.

Figure 1: Inflation, and GDP growth across monetary policy frameworks5

Wellbeing of our people

Inflation has been low and stable in New Zealand for nearly 30 years.

There is a greater appreciation that low inflation is a means to an end, and not the end itself. In the fight to lower inflation that was perhaps easy to forget. The end goal is, of course, improving the wellbeing of our people.6

For many in the general public, employment is one tangible measure of wellbeing. Employment can provide an opportunity to earn your own wage, contribute to society, and live a fulfilling life.

It is in this light that the Reserve Bank Act (1989) has been amended to include a dual mandate with an employment objective alongside our price stability goal. Incorporating the objective of supporting maximum sustainable employment, and equally weighting it alongside inflation, emphasises our long-term goal of improving New Zealanders’ wellbeing. This aligns us with the needs of the public. And it helps us renew our social licence to operate – the first building block for maintaining our credibility.

But it is not enough for the public to believe in and understand our objectives. We must also prove to them that they can be achieved. This brings us to the second building block necessary for maintaining credibility: establishing modern governance principles for dealing with modern problems, and translating good governance into good decisions.

Good governance

In preparing for our dual mandate, and a formal Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), we have updated the principles and processes that form our governance framework for monetary policy.

In pursuit of greater transparency, we have also published these principles and processes in a comprehensive Monetary Policy Handbook (the Handbook). 7 This is an essential document, for everyone from school students to MPC members.

Importantly, it is also a living document that will evolve as our understanding evolves.

Principles

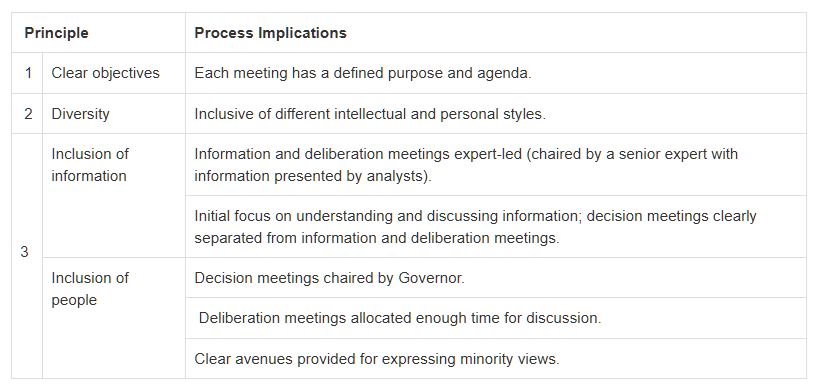

The first part of the Handbook I would like to cover is the section on MPC deliberation principles. 8

Figure 2: MPC deliberation principles

There are three principles which guide the deliberations within the MPC.

I’ve talked already about providing clarity around our objectives – the equal weighting of our employment and inflation goals. This is the first of our three principles.

The second, is diversity – diversity in the skills, experiences, thoughts, and personal characteristics of the MPC members.

The third, is inclusion – inclusion of information and people, ensuring decisions are made on the basis of all the available insights, and reflecting the views of all of the committee members.

Why are diversity and inclusion so important?

The governance literature shows that diversity and inclusion improves the pool of committee knowledge, insures against extreme views, and reduces groupthink.9 These principles drive the committee towards an unbiased policy decision – the best that is possible given existing information.

Think about this from a practical perspective. Modern monetary policy is confronted by diverse issues such as climate, technological, and other structural and social changes. A sole decision maker or uniform committee cannot possibly hope to possess the broad range of insights necessary to consider these issues.

A diverse committee operating in an inclusive environment can. It is these additional insights that improve collective understanding, and lead to better monetary policy decisions.

So you see these principles are not simply rhetorical devices. They are carefully chosen pillars to support our credibility though good decision making in achieving our dual mandate.

Good decision making

Processes

Our principles of good governance have directly influenced the policy-setting process of the MPC. 10 This is a process that has been designed with consensus-based decision making front and centre, consistent with the agreement with the Minister of Finance. 11

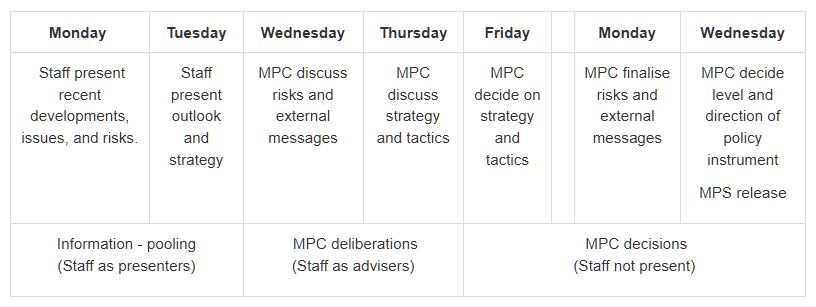

Figure 3: The structure of the forecast week for quarterly Monetary Policy Statements

We begin with information pooling, which flows through to MPC deliberations, and culminates in the final decision making meeting.

As you can see, the policy-setting framework is highly collaborative and deliberate. Deliberate in the sense that the process inspires lively debate, giving MPC members every possible chance to challenge assumptions, critique policy judgements and assess a range of policy strategies to achieve our dual mandate objectives.

A crucial part of this is that the MPC members hold back their views on the decision until the final stages, rather than starting with them. This supports evidence-based decision making and guards against confirmation bias.

The process begins with open information pooling on recent developments and the outlook for the economy. Here, the MPC have the opportunity to investigate and challenge the assumptions made in the staff’s initial forecasts. This is where the MPC member’s judgement enters the picture, and where creative tensions improve collective understanding.

While the MPC members may enter the room with different insights and questions about the economy, at the end of the information pooling stage the committee shares a common reference point for the economic outlook.

There are numerous opportunities to discuss and reflect on key issues, judgements, risks, strategy, and communication throughout the week. There are also a number of anonymous internal surveys we perform to gauge collective opinion among staff and MPC members.12

By the end of the week-and-a-half, the final monetary policy decision reflects the greater momentum of the MPC’s discussion.

We publish the final Official Cash Rate (OCR) decision, a Monetary Policy Statement (MPS), and a Summary Record of Meeting at the same time.

The Summary Record of Meeting captures the key judgements and risks underpinning the central forecasts and decision, as well as indicating where members of the MPC had different views. We identify any differing views, and communicate where the most significant uncertainties lie in our baseline forecasts.13 If consensus cannot be reached, a vote by simple majority would be carried out, and the reasoning behind different stances disclosed in the Summary Record of Meeting.

Our desire is that the transparency provided in the Handbook can help the public understand how the Bank’s collective ‘mind’ works. If the public can see the analytical rigour in our decision making, they should have greater confidence in the MPC’s conclusions, and thus more faith in the Reserve Bank.

Our credibility will be supported in the long run if the decisions made by the MPC are unbiased and effective ones. Our results will speak louder than our words.

Monetary policy strategy and our May decision

So far I’ve talked about the principles and processes we follow in setting policy. Now I’m going to cover how we ‘walk the talk’ in formulating our monetary policy decisions.14

Sound and effective monetary policy strategy requires more than just deciding whether the OCR should go up or down on any given day; instead central banks need to be transparent about their views of the economy over the medium-term and how monetary policy might respond to a changing economic landscape.

In this regard, around twenty years ago, the Reserve Bank became a pioneer in another way. When publishing our interest rate decisions, we also began to publish a forward (and endogenous) projection of interest rates in the future. We use this to capture the overall stance of monetary policy.

This tool remains integral to how the MPC sets monetary policy and understands the potential trade-offs with a dual mandate.

The first monetary policy decision of the new MPC occurred last month, in May. Our starting point was a New Zealand economy where the labour market was operating near maximum sustainable employment, and annual core inflation pressures were within our 1 to 3 percent target range but below the 2 percent mid-point.

We discussed the slowdown in global growth, and how this might affect New Zealand. We also addressed the recent loss of domestic economy momentum since mid-2018, through both tempered household spending and restrained business investment.

In order to continue achieving our policy objectives, we agreed that additional monetary stimulus was needed to help bring inflation back to the 2 percent mid-point and support maximum sustainable employment. We then turned to the question of the magnitude of stimulus we wanted to adopt (the stance) and the timing and means by which we would try to deliver this (the tactics).

Figures 4–6 show how different OCR paths could have been used to achieve our objectives. While each path was consistent with meeting our objectives, they each offered different trade-offs.15

Figure 4: Official Cash Rate (OCR) paths to achieve alternative monetary policy stances

Figures 5-6: Inflation, and employment gap under alternative OCR paths

If we kept rates unchanged (the higher OCR path), our projections suggested that it would have taken a number of years for inflation to return to target, and employment would have fallen below the maximum sustainable level. If we lowered the OCR by around 75 basis points over the next 12 months (the lower OCR path), our projections suggested it would result is a situation where both inflation and employment would be overshooting their targets.

By contrast, the baseline (our final published projection), with the OCR around 40 basis points lower over the next 12 months, brought inflation back to target in a reasonable time period, with employment remaining near the maximum sustainable level. We decided this path captured our preferred strategy, and was robust to the key risks we had discussed.

After agreeing on the appropriate stance of monetary policy, MPC turned to the tactical decision of where to set the OCR at the May meeting, and decided to cut the OCR by 25 basis points to provide a more balanced outlook for interest rates.

This brings us to discuss the future.

Maintaining credibility in the future

Our central view is that New Zealand’s interest rates will remain broadly around current levels for the foreseeable future. However, we need to be ready to adapt to changing conditions, to meet our objectives even when confronted with unforeseen developments.

An issue that policymakers and academics are grappling with around the world is the role of both monetary and fiscal stimulus in a world of low interest rates.

There is emerging consensus that coordination is necessary for an optimal response of broader macroeconomic policy.16 For central banks, operational independence does not have to mean operational isolation. Rather, collaboration with government can be done in a way that builds and reinforces the social licence to operate, by showing a willingness to work with other partners to do whatever is necessary to achieve the broader objective—improving public wellbeing.

Even with coordination between monetary and fiscal policy, if further macroeconomic stimulus is needed quickly, the first line of defence will still inevitably fall upon central banks.17

In New Zealand, we are in the strong position of having further room to provide conventional monetary stimulus if required (using the OCR).

Having effective unconventional policy options expands the toolbox of a central bank, which is naturally more relevant in a low interest rate environment. In this spirit, we published a Bulletin article last year on the practicalities of unconventional monetary tools in a New Zealand context, and we continue to learn from the lessons of our central banking cousins.18

It’s better to have a tool and not need it, than need one and not have it.

Conclusion

In the Handbook, we explore the history of central banking objectives, and see how dramatically they have evolved over time. 19 We haven’t always had a mandate to support maximum sustainable employment, or to achieve price stability, or even control over interest rates or the money supply.

Nothing lasts forever, and it is possible that the role of central banks may change again in the future. Our Handbook will inevitably change. We need to be ready to adapt when changes beckon.

And it is not enough to grudgingly adapt. In order to maintain credibility, central banks must embrace change and prove to the public that they are capable of delivering on their objectives. To remain credible is to remain relevant. Central banks should keep their eyes open, and be ready to change tack. Our destination—a world with improved wellbeing for our citizens—may not change, but the best route for getting there may.

We must adapt. We must continue to improve the wellbeing of our citizens. We must remain credible.

Meitaki.

Thank you.