The Productivity Commission, Australian Government’s independent research and advisory body has released its draft report into Competition in the Australian Financial System. It’s a Doozy, and if the final report, after consultation takes a similar track it could fundamentally change the landscape in Australia. They leave no stone upturned, and yes, customers are at a significant disadvantage. Big Banks, Regulators and Government all cop it, and rightly so.

Australia’s financial system is without a champion among the existing regulators — no agency is tasked with overseeing and promoting competition in the financial system. The Commission’s draft report into Competition in the Australian Financial System recognises that both competition and financial stability are important to the Australian financial system, and are an uncomfortable mix at times. It has also found that competition is weakest in markets for small business credit, lenders’ mortgage insurance, consumer credit insurance and pet insurance.

Here are some of the key findings.

Whilst there has been significant innovation (enabled by technology), the financial system is highly profitable and concentrated. It lacks strong pricing rivalry – and evidence that it exploits loyal customers.

It questions whether the four pillars policy is still relevant. It is an ad hoc policy that, at best, is now redundant, as it simply duplicates competition and governance protections in other laws. At worst, in this consolidation era it protects some institutions from takeover, the most direct form of market discipline for inefficiency and management failure. All new entrants to the banking system over the past decade have been foreign bank branches, usually targeting important but niche markets (and these entrants have evidenced only limited growth in market share).

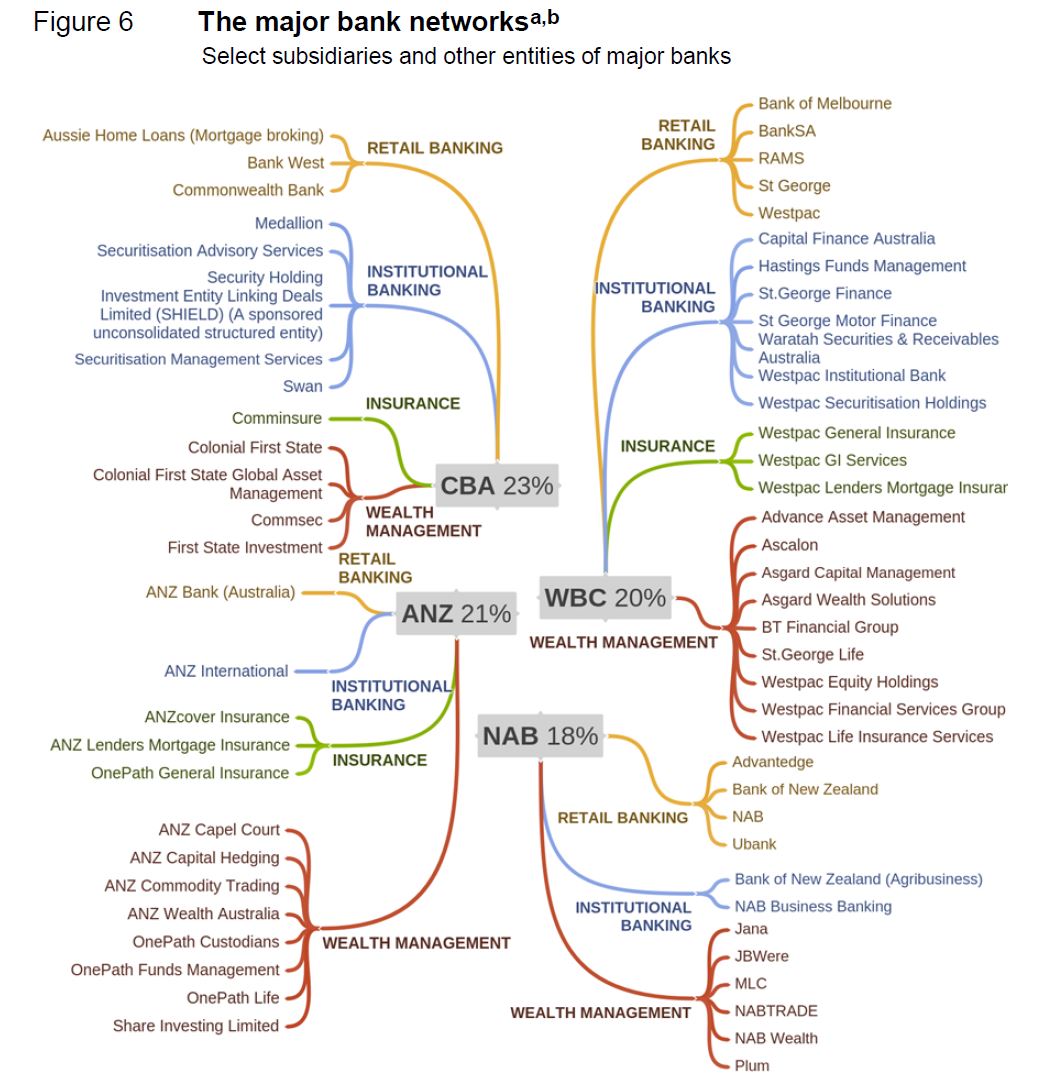

Australia’s financial system is dominated by large players — four major banks dominate retail banking, four major insurers dominate general insurance, and some of these same institutions feature prominently in funds and wealth management. A tail of smaller providers operate alongside these institutions, varying by market in length and strength.

Across the financial system, there is a continual flow of new products and a re-packaging of existing products to appeal to specific groups of consumers. As a consequence, there is a very large number of products in financial markets, with sometimes only marginal differences between them: nearly 4000 different residential property loans and 250 different credit cards are on offer, for example. The same situation is apparent in insurance markets: the largest 4 general insurers hold more than 30 brands between them. In the pet insurance market this is particularly pronounced — 20 of the 22 products (with varying premiums) on offer are underwritten by the same insurer.

Across the financial system, there is a continual flow of new products and a re-packaging of existing products to appeal to specific groups of consumers. As a consequence, there is a very large number of products in financial markets, with sometimes only marginal differences between them: nearly 4000 different residential property loans and 250 different credit cards are on offer, for example. The same situation is apparent in insurance markets: the largest 4 general insurers hold more than 30 brands between them. In the pet insurance market this is particularly pronounced — 20 of the 22 products (with varying premiums) on offer are underwritten by the same insurer.

Banks can price as they want. Little switching occurs — one in two people still bank with their first-ever bank, only one in three have considered switching banks in the past two years, with switching least likely among those who have a home loan with a major bank. ‘Too much hassle’ and a desire to keep most accounts with the same institution are the main reasons given for the lack of switching, with home loans being a particularly difficult product for consumers to switch.

Although financial institutions generally have high customer satisfaction levels, customer loyalty is often unrewarded with existing customers kept on high margin products that boost institution profits. For this to persist, channels for provision of information and advice (such as mortgage brokers) must be failing.

Scope for price rivalry in principal loan products is constrained by a number of external factors: price setting by the Reserve Bank facilitating price coordination by banks; expectations of ratings agencies that large banks are too big to fail; and some prudential regulation (particularly in risk weighting) that favours large institutions over smaller ones.

The growth in mortgage brokers and other advisers does not appear to have increased price competition. The revolution is now part of the establishment. Non-transparent fees and trailing commissions, and clear conflicts of interest created by ownership are inherent. Lender-owned aggregators and brokers working under them should have a clear best interest duty to their clients.

There is also variation between larger and smaller institutions in funding costs (with a large regulatory-determined component). Not all ADIs face the same regulatory arrangements and regulatory effects on their pricing capacity. A source of differential funding costs to banks is a series of regulatory measures and levies that apply (both positively and negatively) to the major Australian-owned banks but not to smaller Australian-owned ADIs or foreign banks operating in Australia.

The net result of these regulatory measures is a funding advantage for the major banks over smaller Australian banks that rises in times of heightened instability. RBA estimated this advantage to have averaged around 20 to 40 basis points from 2000 to 2013 (worth around $1.9 billion annually to the major banks). More recently, the funding cost advantage of major banks has been estimated to have declined to about 10 basis points, due in part to prudential reforms. But it nevertheless persists, and ratings agencies are unlikely to rate institutions’ fund raising such that there is no effective differential between Australia’s major and smaller banks.

Australia’s major banks have delivered substantial profits to their shareholders — over and above many other sectors in the economy and in excess of banks in most other developed countries post GFC. In recent times, regulatory changes have put pressure on bank funding costs, but by passing on cost increases to borrowers, Australia’s large banks in particular have been able to maintain high returns on equity (ROEs).

The ROE on interest-only investor loans doubled, for example, to reach over 40% after APRA’s 2017 intervention to stem the flow of new interest-only lending to 30% of new residential mortgage lending (reported by Morgan Stanley). This ROE was possible largely due to an increase by banks in the interest rate applicable to all interest-only loans on their books, even though the regulator’s primary objective was apparently to slow the growth rate in new loans. Competing smaller banks were unable to pick up dissatisfied customers from this re-pricing of their loan book because of the application of the same lending benchmark to them.

Regulators have focused on a quest for financial stability prudential stability since the Global Financial Crisis, promoting the concept of an unquestionably strong financial system.

The institutional responsibility in the financial system for supporting competition is loosely shared across APRA, the RBA, ASIC and the ACCC. In a system where all are somewhat responsible, it is inevitable that (at important times) none are. Someone should.

The Council of Financial Regulators should be more transparent and publish minutes of their deliberations. Under the current regulatory architecture, promoting competition requires a serious rethink about how the RBA, APRA and ASIC consider competition and whether the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) is well-placed to do more than it currently can for competition in the financial system.

Some of APRA’s interventions in the market — while undertaken in a way that is perceived by the regulators to reflect competitive neutrality — have been excessively blunt and have either ignored or harmed competition. Such consequences for competition were neither stated nor transparently assessed in advance. APRA’s interpretation of Basel guidelines on risk weightings that non-IRB banks use for determining the amount of regulatory capital to hold, puts it among the most conservative countries internationally.

- For home loans, the main area in which Australia’s risk weights vary from international risk weightings is for (lower risk) home loans that have a loan to value ratio below 80%.Australian non-IRB lenders are required to use a risk weight of a flat 35%, compared with Basel-proposed guidelines of 25% to 35% for such loans.

- For small and medium enterprise (SME) loans, the main area of difference is lending that is not secured by a residence. A single risk weight (of 100%) applies to all SME lendingnot secured by a residence, with no delineation allowed for the size of borrowing, the form of borrowing (term loan, line of credit or overdraft) or the risk profile of the SMEborrowing the funds. In contrast, Basel proposed risk weights for SME lending vary from75% for SME retail lending up to €1 million, to 150% for lending for land acquisition, development and constructions.

The RBA should establish a formal access regime for the new payments platform (NPP). As part of this regime, the RBA should review the fees set by participants of the NPP and transaction fees set by NPPA; and require all transacting participant entities that use an overlay service to share de-identified transaction-level data with the overlay service provider.

Measures that should be prioritised to help consumers become a competitive force in the longer term include:

- consumer rights to have their financial data transferred directly from one service provider to another, either facilitated through Open Banking arrangements or as part of a more broadly-based consumer data right

- automatic reimbursement of the ‘unused’ portion of lenders mortgage insurance when a consumer terminates the loan

- payment system reforms that help detach consumers from their financial providers

- provision of information on median home loan interest rates provided in the market over the previous month

- inclusion on insurance premium notices, of the previous year’s premium and percentage change.