The densification of Australian cities has been heralded as a boon for housing choice and diversity. The up-beat promotion of “the swing to urban living” by one of Australia’s leading developer lobby groups epitomises the rhetoric around this seismic shift in housing.

Glossy advertisements for luxury living in our city centres and suburbs adorn the property pages of our newspapers.

Brochures boast of breathtaking city views from uppers storeys and gush about amenity, lifestyle and “liveability” – often touting the benefits of adjacent public infrastructure investments (but please don’t mention “value sharing”).

Depictions of attractive younger people, occasionally clutching a smiling infant, are prominent as the image of all things new, urban and desirable.

Long gone are the days when the manifestations of property marketeers’ imaginations were restricted to images of low-density master-planned estates on the urban fringe. We hardly ever hear about these nowadays.

There’s truth in the claims that housing choice and diversity have indeed widened in the last few decades as a result. The statistics clearly show a much greater spread of dwelling options in our cities.

The rise and rise of the apartment block

Apartments now account for 28% of housing in Sydney and 15% in Melbourne. As the maps below show, most recent growth in apartment stock is clearly in and around the inner city. Yet even the more distant suburbs have had an increase in higher-density residential development.

Changes in the number of flats and apartments, 2011 to 2016, in Sydney (above) and Melbourne (below). Data: ABS Census 2011, 2016, Author provided

Changes in the number of flats and apartments, 2011 to 2016, in Sydney (above) and Melbourne (below). Data: ABS Census 2011, 2016, Author provided

Data: ABS Census 2011, 2016, Author provided

Data: ABS Census 2011, 2016, Author provided

For many, inner-city apartment living is clearly a preferred choice for the stage in their life when an upcoming, “vibrant” neighbourhood is attractive. High-density urban renewal has been a boon for hipsters and students alike.

But the issue of choice needs to be unpacked carefully. For many others, the “swing to urban living” is more of a necessity.

True, the surge in apartment building has put many properties onto the market to rent or buy that are clearly cheaper than houses in the same suburb. From that point of view, they have added to the affordability of these neighbourhoods.

However, affordable to whom is an open question. At A$850,000 and upwards for a standard two-bedder in Waterloo, South Sydney, and $500,000 or more in Melbourne’s Docklands for a similar property, these are not exactly a cheap option for anyone on a low income.

But other than in the prestige areas where higher-income downsizers and pied-à-terre owners can be enticed to buy in some comfort, much of what is being built is straightforward “investor grade product” – flats built to attract the burgeoning investment market.

It can be argued that the investor has always been a major target of apartment developers, even in the 1960s and 1970s when strata units became common, particularly in Sydney. But it is even more so today.

Despite the clamour to control overseas investors perceived to be flooding the market, the bulk of investors are home grown. We don’t need to rehearse the debates on the factors that have fuelled this splurge, but clearly the development industry has been savvy to the possibilities of this market.

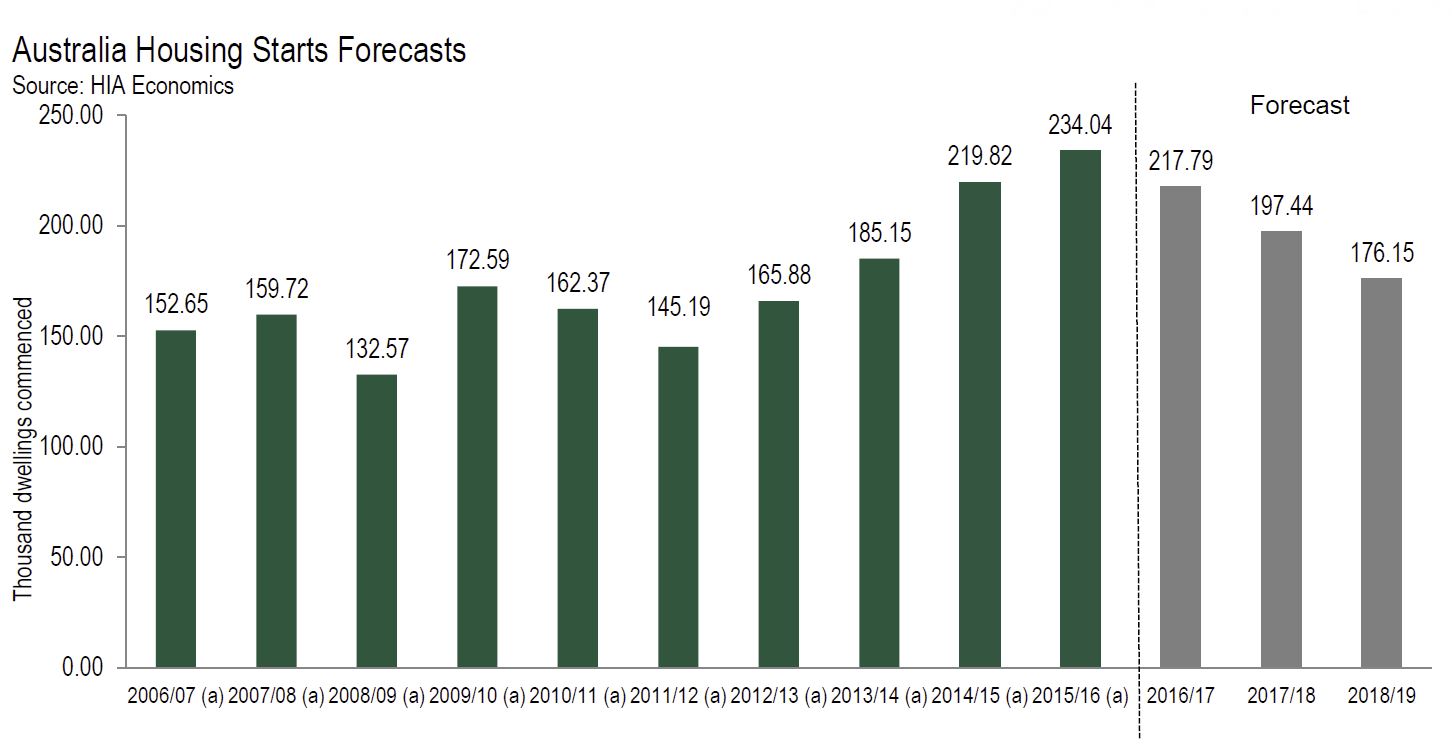

In the last decade, backed by state planning authorities and politicians desperate to claim they have “solved” housing affordability by letting apartment building rip, developers have got involved on an unprecedented scale. The figures bear this out: in 2016, for the first time, Australia built more apartments than houses. The majority end up for rent.

Problematic products with too few protections

In the rush, we, the housing consumer, have been offered a motley range of new housing with a series of escalating problems. Leaving aside amateur management by owners’ bodies in charge of multi-million-dollar assets, problems of short-term holiday lettings and neighbour disputes, there are more serious concerns over build quality, defective materials and fire compliance.

The apartment market has been left wide open for poor-quality outcomes by building industry deregulation. This includes:

- moves toward complying development approval for high-rise;

- self-certification of building components;

- complex design and non-traditional building methods;

- relaxation of defect rectification requirements;

- long chains of sub-contractors;

- poor oversight by local planners and authorities; and

- cheap or non-compliant fittings and finishes.

Plus there’s the rush to get buildings up and sold off. Not to mention fly-by-night “phoenix” developers who vanish as soon as the last flat is occupied, never to be found when the defects bills come in.

The lack of consumer protection in this market is astounding. The average toaster comes with more consumer protection – at least you can get your money back if the product fails.

‘Vertical slums’ in the making

These chickens will surely come home to roost in the lower end of the market, which will never attract the wealthy empty-nesters or cashed-up young professionals with the resources to ensure quality outcomes.

In Melbourne, space and design standards, including windowless bedrooms, have come under critical scrutiny, as has site cramming. Tall apartment blocks stand cheek-by-jowl in overdeveloped inner-city precincts.

At least New South Wales has State Environmental Planning Policy 65, which regulates space and amenity standards, and the BASIX environmental standard to prevent the more egregious practices.

But people are most likely to confront the problems of density in the many thousands of new units adorning precincts around suburban rail stations and town centres. These have been built under the uncertain logic of “transport-orientated development”, often replacing light industrial or secondary commercial development.

These developments attract a mixed community of lower-income renters. Many are recently arrived immigrants and marginal home buyers – often first-timers. Many have young children, as these units are the only option for young families to buy or rent in otherwise unaffordable markets. Overall, though, renters predominate.

What will be the trajectory of these blocks, once the gloss wears off and those who can move on do so? You only have to look at the previous generation of suburban walk-up blocks in these areas to find the answer.

Far from bastions of gentrification, the large multi-unit buildings in less prestigious locations will drift inexorably into the lower reaches of the private rental market.

Town centres like Liverpool, Fairfield, Auburn, Bankstown and Blacktown in Sydney point the way. The cracks in the density juggernaut are already showing in many of the more recently built blocks in these areas – literally, in many cases.

This inexorable logic of the market will create suburban concentrations of lower-income households on a scale hitherto experienced only in the legacy inner-city high-rise public housing estates.

With the latter being systematically cleared away, the formation of vertical slums of the future owned by the massed ranks of unaccountable, profit-driven investor landlords is a racing certainty. The consequences are all too easy to imagine.

The call for greater regulation of apartment, planning, design and construction is being heard in some quarters. The 2015 NSW Independent Review of the Building Professionals Act highlights these concerns.

But don’t hold your breath for rapid reform. No-one wants to kill the goose that’s laying so many golden eggs for the development industry and government alike – especially in inflated stamp-duty receipts.

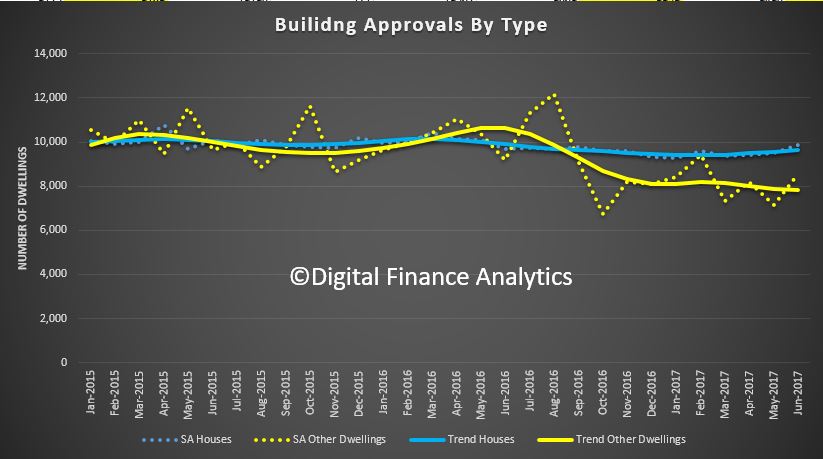

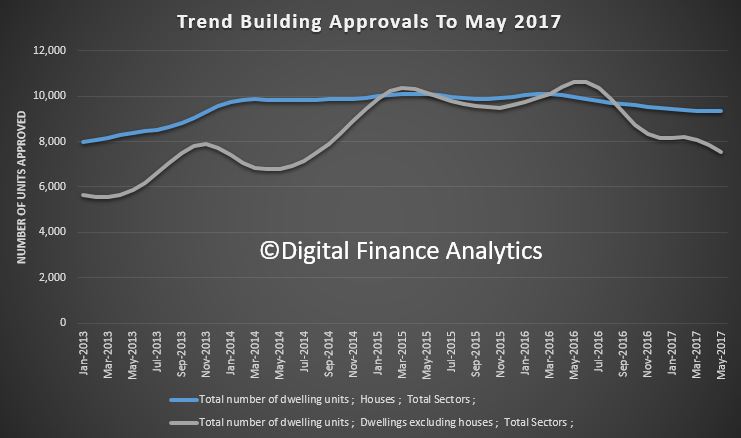

The market has a habit of self-regulating on supply. Evidence of a marked downturn in apartment building is a clear sign of that. But don’t expect the market to self-regulate on quality, at least with the current highly fragmented, confusing (not least to builders and bureaucrats), under-resourced and largely unpoliced regulatory system.

The legacy of this entirely avoidable crisis is completely predictable, but will be for future generations to pick up

Author: Bill Randolph, Director, City Futures – Faculty Leadership, City Futures Research Centre, Urban Analytics and City Data, Infrastructure in the Built Environment, UNSW

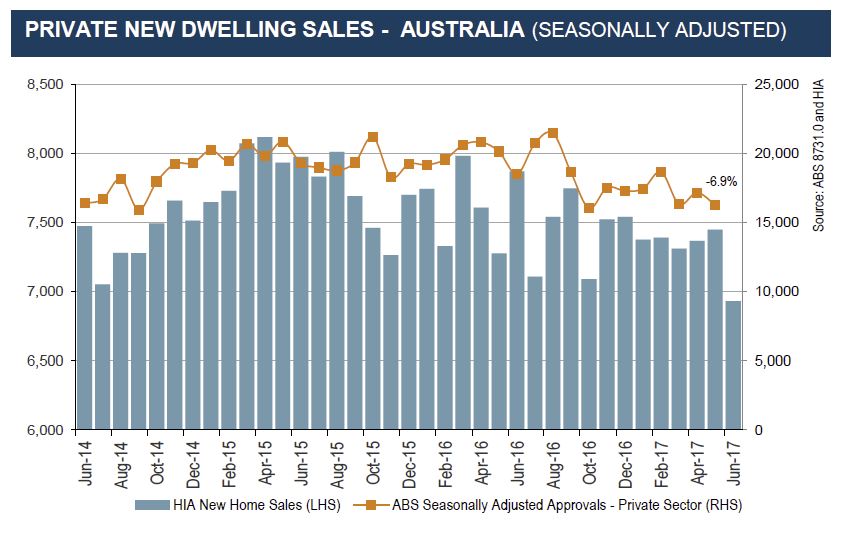

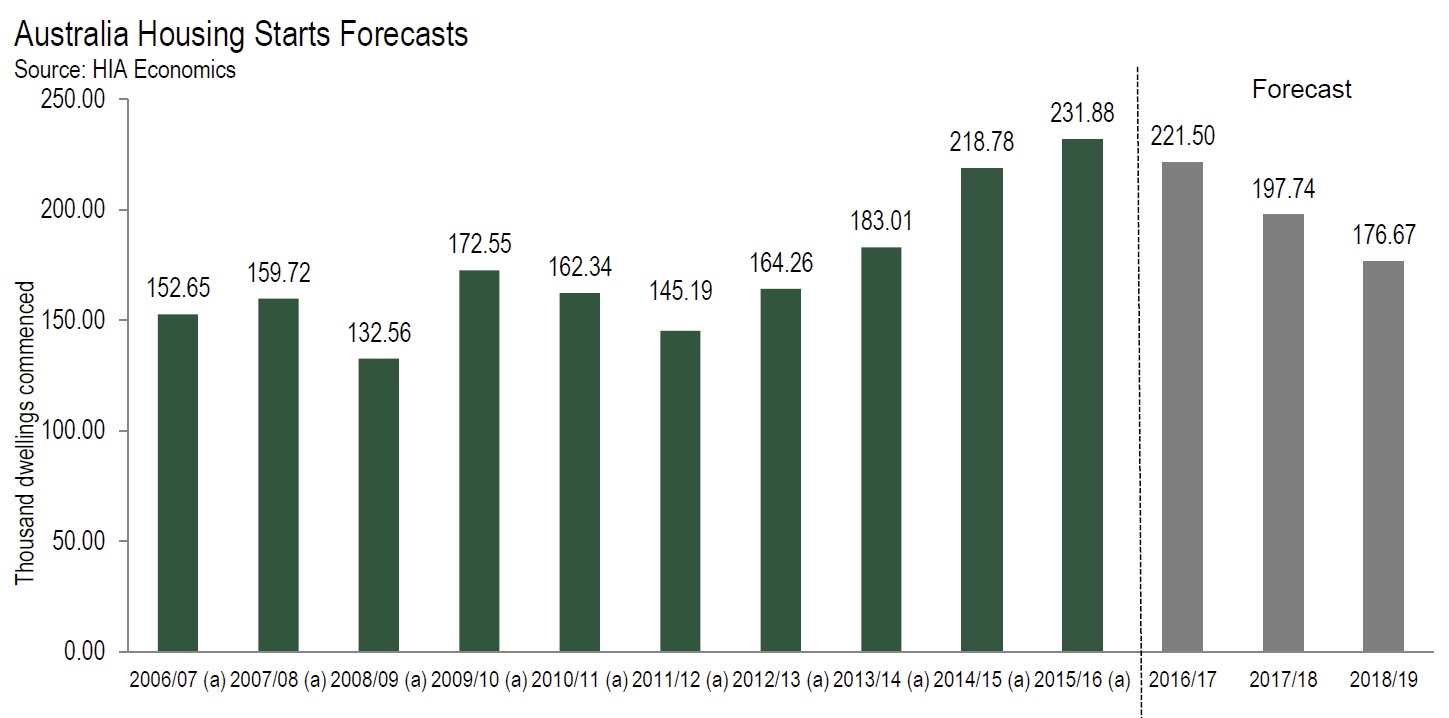

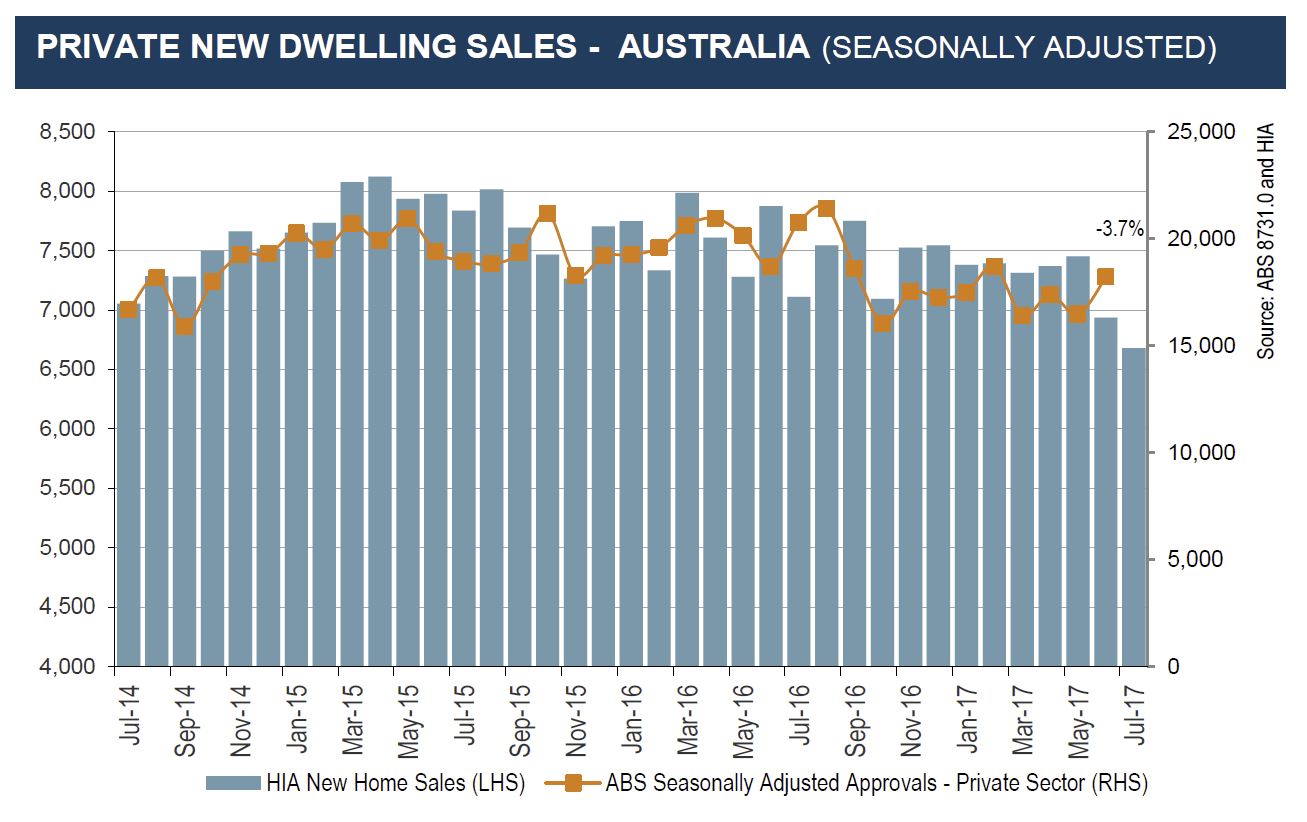

Sales of new detached houses during July 2017 fell by 0.4 per cent nationally to their lowest level since October 2014. Victoria was the only state to experience growth (+9.8 per cent). Detached house sales fell in South Australia (-16.2 per cent), Queensland (-16.1 per cent), Western Australia (-9.1 per cent) and New South Wales (-5.2 per cent) during the month.

Sales of new detached houses during July 2017 fell by 0.4 per cent nationally to their lowest level since October 2014. Victoria was the only state to experience growth (+9.8 per cent). Detached house sales fell in South Australia (-16.2 per cent), Queensland (-16.1 per cent), Western Australia (-9.1 per cent) and New South Wales (-5.2 per cent) during the month.