In the last episode of the three-part series on the future of fintech, Baker & McKenzie looks ahead and examines both where some of the opportunities lay and where some of the challenges will be.

Digital Finance Analytics (DFA) Blog

"Intelligent Insight"

In the last episode of the three-part series on the future of fintech, Baker & McKenzie looks ahead and examines both where some of the opportunities lay and where some of the challenges will be.

ASIC has warned firms and issuers involved in initial public offerings (IPOs) in Australia to ensure their marketing campaigns comply with the letter and spirit of the law, particularly when using emerging social-media strategies.

An ASIC review of marketing practices in IPOs has found that so-called ‘traditional’ means of communication – telephone calls, emails and websites – remain more important for the marketing of an offer to retail investors. The review found that the use of social media is not yet pervasive; it is only used occasionally by small to medium-sized firms to market IPOs.

REP 494 Marketing practices in initial public offerings of securities details the review’s findings, highlights areas of concern and provides for consideration ASIC’s recommendations to improve marketing practices for IPOs in the future.

Between October 2015 and March 2016 ASIC reviewed the online and social media marketing of 23 IPOs where a prospectus was lodged. ASIC then conducted a more extensive review of the marketing practices and materials of 17 firms that were involved in 7 of the original IPOs. ASIC also monitored the marketing of other IPOs as part of its usual prospectus review work.

Key findings of the report included:

- There were some oversight weaknesses in relation to marketing done via telephone calls and social media, and in ensuring that marketing material is kept up to date.

- The use of forecasts in communications or the targeting of investors from a particular background means special care may need to be taken to avoid misleading investors.

- Firms and issuers did not always properly control access to information about the offer to ensure retail investors base their decision on the prospectus; and

- Some good practices were adopted by firms to ensure that communication was consistent with the prospectus information.

ASIC Commissioner John Price said the purpose of the review was to understand current market practices and identify areas of particular concern.

‘The way that an IPO is marketed may unduly influence the decision to invest in an IPO,’ he said.

‘We are living in more innovative times where we are seeing new interactive methods of communication and marketing used in many corporate and commercial arenas, including taking a company public. While we embrace such innovation, we also want to remind firms and issuers to ensure that their marketing practices comply with the advertising and publicity restrictions in the Corporations Act,’ he said.

Infrastructure in our cities – let’s call it the hardware – remains much the same as ever, but the software – the way we use it – is transforming rapidly. One piece of that software, Airbnb, is dramatically reshaping the world’s cities.

The digital platform allows citizens to find and rent short-term accommodation from other citizens. Airbnb has the potential to rupture the traditional spatial relationship between tourist and local, making our cities more vibrant and diverse places to live in and to visit.

The question is: what opportunities and dangers does the platform present? What are the implications of repurposing existing residential infrastructure for short-term accommodation? What happens when the global “sharing economy” meets a city’s suburbs?

Lessons from an early adopter

Melbourne was an early adopter of Airbnb. It is also one of the top 10 cities for global travellers on Airbnb. What insights can be gathered from its experience?

According to Airbnb, three-quarters of listings worldwide are outside major hotel districts. Airbnb has three types of property listings: entire homes, private rooms and shared rooms.

Concentration of Airbnb entire-house rentals in Melbourne. Jacqui Alexander & Tom Morgan, Author provided

Entire homes make up over half the total number of Melbourne’s metropolitan listings. Data collected in January 2016 reveals that their distribution is relatively consistent with that of hotels and licensed accommodation, which exist in large concentrations in the CBD and inner city. Many hosts who list entire homes lease or sublet when they go away.

In Australia, tenants require permission from their landlord to sublet, so there is little risk for the landlord if they follow due process. But analysis by website Inside Airbnb indicates that about 75% of entire-house listings in Melbourne are available for over 90 days per year. Hosts with multiple properties manage about a third of all the entire-house listings in Melbourne. These operators hold an average of three properties, but some have dozens. Through Airbnb, these brokers are turning existing housing infrastructure into informal, distributed hotels while saving on capital costs, overheads and wages.

Globally, the Airbnb phenomenon has been blamed for driving up rents, accelerating gentrification and displacing local residents by reducing available housing stock. In Melbourne, the boom in high-density development in the CBD has resulted in an excess of homogeneous apartment dwellings. Bedrooms without natural light, as well as insufficient floor area, outdoor space and storage space, characterise many of these developments, rendering them effectively unlivable for long-term residents. But these properties are attractive to itinerant tenants seeking affordable inner city accommodation.

Concentration of Airbnb shared-room rentals in Melbourne. Jacqui Alexander & Tom Morgan, Author provided

Shared rooms in Melbourne constitute only about 2% of all listings, but they are almost exclusively confined to the CBD. Box Hill (14 kilometres east of Melbourne), and Maidstone/ Braybrook (eight kilometres west of Melbourne) are secondary outlying hotspots. The majority of CBD listings are around new apartment towers near Southern Cross Station (at the western end of the CBD) and RMIT University.A number of already small two-bedroom apartments in the Neo200, Upper West Side and QV1 towers are operating as gendered dormitories. These often sleep eight, with four to a room. Overloading these apartments creates potential fire-safety and hygiene-compliance issues.

Short-term letting via sites like Airbnb allows investors to earn up to three times the amount they’d receive in rent (the average cost to rent an entire home is AU$189 per night). Travellers benefit from competitive accommodation rates, cooking facilities, convenient locations and access to private pools and gymnasiums intended for residents.

Airbnb acknowledges that professional hosts with multiple listings are exploiting the so-called sharing economy, but has not yet taken steps to regulate this. Governments would do well to implement the long-awaited and much-needed minimum design standards for apartments to curb the construction of developments in the city that fail to cater for residents or which are purpose-built for the Airbnb market (a few local examples are already emerging).

Beyond the obvious need to protect the amenity of citizens, protection of the liveliness and heterogeneity of the city is essential to maintain the kind of “authentic” experience that appeals to Airbnb users in the first place. Melbourne is beginning to follow the trajectory of international cities like London where the investor market, fuelled by capital gains tax exemptions, has pushed residents further and further out. Dispersing the concentration of entire-house and private-room rental is vital.

Concentration of Airbnb private room rentals in Melbourne. Jacqui Alexander & Tom Morgan, Author provided

More promising is the dispersed pattern of private rooms in Melbourne. These represent around 45% of listings across the city. While private rooms are still concentrated in and around the CBD, diffuse listings across Melbourne’s middle-ring suburbs realise Airbnb’s ambition to enable access to the everyday spaces of cities. This pattern makes sense given the mismatch between Australian house sizes, which remain the largest in the world, and changing household structures – most significantly, the decline of the nuclear family. An increase in housing diversity in the middle-ring suburbs is likely to facilitate more entire-house listings in these areas in the future.

We are also seeing evidence of Airbnb driving housing diversity. Annexed and granny-flat configurations are commonly listed in suburbs close to the Melbourne CBD like Brunswick and Caulfield. Loose-fit arrangements like these provide more flexibility to cater to both residents and visitors, and the by-product is slow but genuine “bottom-up” densification.

Government incentives for this kind of small-scale development would help to make this a viable (and, for many, welcome) alternative to densification through high-rise apartment development.

In 2015, Tourism Victoria entered into an agreement with Airbnb Melbourne to promote buzzing inner-city suburbs Fitzroy and St Kilda as “sharing economy” hotspots. But the cost of renting in these suburbs is already exorbitant. Fitzroy was named the second-most-expensive suburb in Melbourne for apartment rental in 2015.

Instead, policymakers could encourage disruption in the suburbs that would benefit both sides.

What can be done to capture local benefits?

Airbnb claims that tourists who use the platform “stay longer and spend more”. Through taxation and additional revenue from the sharing economy, governments could fund more extensive and efficient transport networks to service both locals and visitors. Extending transport infrastructure would support the intensification of distributed neighbourhoods and maximise intermingling between tourists and locals.

Airbnb rentals in Perth. Jacqui Alexander, Author provided

Bottom-up densification could also be a way forward for Perth. The distribution of Airbnb accommodation towards Perth’s coastal suburbs highlights potential in this space: here, tourism-specific and local infrastructure can converge. This is an exciting prospect for a state that positions itself as a unique travel destination.

Airbnb emerges from the same cultural tendency as the pop-up shop and interim-use place activation. Built environment professionals must recognise it as an urban issue and lead with a framework for targeted, productive disruption.

Airbnb can increase the density of people within existing building stock, while dispersing the positive effects of the tourist economy. This requires more imagination from planners and designers, who first and foremost must consider the interests of individual citizens, whether they are renters or home owners.

Can Airbnb be a part of the solution of increasing urban infill without compromising a minimum standard of living?

The Conversation is co-publishing articles with Future West (Australian Urbanism), produced by the University of Western Australia’s Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Visual Arts. These articles look towards the future of urbanism, taking Perth and Western Australia as its reference point. You can read other articles here.

Recent discussion about freedom of speech in Australia has focused almost exclusively on Section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act. For some politicians and commentators, 18C is the greatest challenge to freedom of speech in Australia and the reform or repeal of this section will reinstate freedom of speech.

There are many challenges to freedom of speech in Australia beyond 18C, for example defamation law. Defamation law applies to all speech, whereas 18C applies only to speech relating to race, colour or national or ethnic origin.

The pervasive application of defamation law to all communication creates real risks of liability for publishers. Large media companies are used to managing those risks. But defamation law applies to all publishers, large and small. Now, through social media, private individuals can become publishers on a large scale.

A significant reason that defamation law poses a risk to free speech is that it is relatively easy to sue for defamation and relatively difficult to defend such a claim. All a plaintiff will need to demonstrate is that the defendant published material that identified the plaintiff, directly or indirectly, and that it was disparaging of their reputation.

In many cases, proving publication and identification is straightforward, so the only real issue is whether what has been published is disparaging of the person’s reputation. Once this has been established, the law presumes the plaintiff’s reputation has been damaged and that what has been published is false.

It is then for the publisher to establish a defence. The publisher may prove that what has been published is substantially accurate, or may claim that it is fair comment or honest opinion (but the comment or opinion must be based on accurately stated facts), or may be privileged. Truth, comment and privilege are the major defences to defamation.

One of the main criticisms of 18C is that it inhibits people from speaking freely about issues touching on race. In essence, this criticism is that 18C “chills” speech.

The ability of the law to inhibit or “chill” speech is not unique to 18C. The “chilling effect” of defamation law is well-known. Precisely because it is easier to sue, than to be sued, for defamation, the “chilling effect” of defamation law is significant.

Defamation claims based on social media publications by private individuals are increasingly being litigated in Australia. In 2013, a man was ordered to pay A$105,000 damages to a music teacher at his former school over a series of defamatory tweets and Facebook posts. In 2014, four men were ordered to pay combined damages of $340,000 to a fellow poker player, arising out of allegations of theft made in Facebook posts. In the former case, judge Elkaim emphasised that:

… when defamatory publications are made on social media it is common knowledge that they spread. They are spread easily by the simple manipulation of mobile phones and computers. Their evil lies in the grapevine effect that stems from the use of this type of communication.

More defamation cases arising out of social media can be anticipated. Indeed, the cases that make it to court represent only a fraction of the concerns about defamatory publications on social media. Many cases settle before they reach court and still more are resolved by correspondence before any claim is even commenced in court.

There are several ways in which defamation law might be reformed in Australia that could promote freedom of speech, particularly for everyday communication.

Currently, plaintiffs suing for defamation in Australia do not have to demonstrate that they suffered a minimum level of harm at the outset of their claims. Publication to one other person is sufficient for a claim in defamation, and damage to reputation is presumed. Defamation law is arguably engaged at too low a level in Australia.

English courts have developed two doctrines to deal with low-level defamation claims. It is worth considering whether these should be adopted in Australia.

The first is the principle of proportionality. This allows a defamation claim to be stayed where the cost of the matter making its way through the court would be grossly disproportionate to clearing the plaintiff’s reputation. A court would view such a claim as an abuse of process.

There has been some judicial support for this principle in Australia, most notably Justice McCallum in Bleyer v Google Inc, but there has also been judicial criticism and resistance.

The other English development is the requirement that a plaintiff prove a level of serious or substantial harm to reputation before being allowed to litigate.

Australian law does have a defence of triviality, but it is difficult to establish because of the terms of the legislation. It also only applies after the plaintiff has established the defendant’s liability. By contrast, the threshold requirement of serious or substantial harm can stop trivial defamation claims before they start.

Another way in which the balance between the protection of reputation and freedom of speech online could be effectively recalibrated is by developing alternative remedies for defamation.

Notwithstanding previous attempts at defamation law reform, it remains the case that an award of damages is still the principal remedy for defamation. Yet people who have had their reputations damaged would probably prefer a swift correction or retraction, or to have the material taken down, or have a right of reply, than commencing a claim for damages.

Currently, people can negotiate these remedies by threatening to sue, or suing, and hoping they can secure these remedies as part of a settlement. Australian law has no effective small claims dispute resolution system for defamation in the way that it does for other small claims, such as debts. More effective and more accessible remedies are another aspect of defamation law reform worth exploring.

The discussion about freedom of speech in Australia recently has been unduly narrow. Every Australian has an interest in freedom of speech, not only about issues of race. Every Australian also has an interest in the protection of their reputation.

It is time to widen the focus of the treatment of free speech under Australian law. Defamation law is an obvious area in need of reform on this front.

Author: David Rolph, Associate Professor of Media Law, University of Sydney

Fintch “uno” has received a $16.5m strategic investment from Westpac. uno is a digital mortgage service offering households tools to search, compare and settle a better home loan for themselves online, including realtime chat

uno allows consumers to access real-time home loan rates based on their personal situation – not just advertised rates. These next generation tools– that in the past only a traditional mortgage broker would have access to – allow them to calculate their borrowing power across lenders, save and share their data with someone else getting the home loan, and select the option that best suits their needs. The entire system is built on the premise that if people had the right knowledge and access to information, they could do better for themselves.

The entire uno loan application process can be done from a desktop, tablet and smartphone, and is supported by a team of experts who can help with real-time advice, when a consumer wants it.

So it is an alternative to a mortgage broker and so far they say more than $400m loans have been search for via the platform. uno’s home loan experts that provide advice do not personally receive sales commissions. The company says they take out all of the filters and pre-decisions that traditional brokers apply before making a recommendation to a home buyer and instead offers full transparency, putting decision making power in the hands of the consumer.

The company says: uno is redefining the way property finance is secured by using a ‘technology plus people’ approach to provide the consumer the power to get a home loan that gives them a better deal – from both major and smaller lenders via any digital device with real-time advice and support. Driven by next generation tools and calculators with the capability to provide real-time home loan rates and borrowing power based on a consumer’s personal situation, uno has reimagined how Australians can buy or refinance a home.

The successful launch of unohomeloans.com.au in May this year has attracted a number of high profile investors, such as Westpac, that have discovered the service’s potential to redefine how Australians buy or refinance their home.

The popularity of the unohomeloans.com.au service has grown rapidly as customers have discovered the benefits of having greater power in the home loan search process, and direct access to the technology and information that traditional mortgage brokers use. uno’s offering also includes full-service support and advice for customers via chat, phone and video, helping customers search, compare and settle in the one place.

Founder and CEO of uno, Vincent Turner, said in the three months since launch, millions of dollars’ worth of loans had been settled as customers reviewed their loan position with uno’s service team to find a better deal in today’s low interest rate environment.

Mr Turner said: “We’ve grown to 34 employees to meet the service demands of thousands of registered customers who have used the platform to compare more than $400 million worth of mortgages. With the support of our investors we’ve worked hard to test and enhance the customer experience, as well as finesse the functionality of our original platform to include options such as new calculators and video chat.”

Chief Strategy Officer at Westpac, Gary Thursby, said: “uno’s success has been impressive and we’re seeing its potential to become a serious player in the home loan market. Westpac has been involved since the concept phase, and today we’re pleased to announce we will increase our involvement in uno as a strategic investor. Westpac is proud of its reputation as a supporter of early stage fintech companies like uno that drive digital innovation and benefit Australians.”

Mr Turner added: “We knew from the start that by creating a platform with direct visibility to lenders’ products and pricing, we could give Australians greater control over the home loan process and the confidence to achieve the best home loan deal. We also challenged the status quo by giving customers the ability to search, compare and settle a home loan in the one place, which has proven extremely useful for busy professionals. “With the healthy investment we need to drive the company forward, we are excited to keep expanding and help more people get a better home loan.”

NAB says customers will have more control over how, when and where they use their cards, thanks to NAB’s new Mobile Banking App to be launched later this year.

The new App will include world-leading card transaction controls, making it easier for customers to conveniently and instantly self-manage their personal Visa debit and credit cards through their mobile device.

And, in an Australian first, NAB customers will be able to instantly use newly approved personal Visa credit cards, with an innovative digital contract feature in the new App not seen anywhere else in the world.

This means customers will be able to instantly use their new credit card through NAB Pay for contactless transactions less than $100, without having to wait for their physical card to arrive in the mail.

“This is a whole new platform for a new era of NAB mobile banking,” NAB Executive General Manager of Consumer Lending, Angus Gilfillan, said.

“Our new App will be fast and seamless, and has been designed to make banking as convenient and easy as possible for our customers.”

“We want to give our customers more control over their everyday banking, and our new App will help them to do this with the tap of a button.”

NAB announced a strategic partnership with Visa in November last year, which was designed to accelerate the delivery of payments innovation and product development for customers. Through this partnership, and utilising the capabilities Visa made available through its Visa Developer platform, NAB was able to enhance the card transaction control features in its new Mobile Banking App.

“We’re really pleased to have been able to open up our capabilities which is delivering speed to market and innovation,” Global Head of Visa Developer, Mark Jamison, said.

“By directly connecting Visa and NAB developers through the Visa Developer program, the NAB team was able to save around six months of development time.”

These card transaction control features will enable customers to select and modify when and how their Visa debit and credit cards can be used.

“Customers will be able to control what type of payments can be made through the App; for example, if you’ve provided a secondary card to a family member, you can choose “Don’t Allow” for online purchases on that card,” Mr Gilfillan said.

NAB’s new mobile banking experience will include a range of other features, including the ability for customers to place a temporary block on any card that may have been lost or stolen.

“NAB is absolutely focussed on improving the customer experience, and our new App will give customers more control of their cards so it better suits their individual needs,” Mr Gilfillan said.

The new App will also see improvements to existing features and functions in NAB’s current Mobile Banking App, and, with a new look and feel, it will be easier for customers to login, view account balances, and search past transactions.

An open pilot of the new App will commence soon for compatible Android devices, providing thousands of customers the opportunity to provide feedback. Customers who would like to participate in the pilot will be able to visit the Google Play Store and download the new App. Customers with iOS devices will also be piloting the App over coming weeks.

“Our customers have been and will continue to be extensively involved in the development of our new App because we are absolutely committed to delivering our customers the experience they want,” Mr Gilfillan said.

During the pilot and after the App is launched in full later this year, features on the App will be released in stages.

NAB will also this week launch its new NAB PayTag to customers, a sticker which can be attached to mobile devices to enable contactless payments linked to a customer’s Visa debit card.

“We’re always looking for opportunities to provide our customers with innovative products and services, features and functions, to help them do their banking easier and take control of their finances,” Mr Gilfillan said.

Wherever you go online, someone is trying to personalise your web experience. Your preferences are pre-empted, your intentions and motivations predicted. That toaster you briefly glanced at three months ago keeps returning to haunt your browsing in tailored advertising sidebars. And it’s not a one-way street. In fact, the quite impersonal mechanics of some personalisation systems may not only influence how we see the world, but how we see ourselves.

It happens every day, to all of us while we’re online. Facebook’s News Feed attempts to deliver tailored content that “most interests” individual users. Amazon’s recommendation engine uses personal data tracking combined with other users’ browsing habits to suggest relevant products. Google customises search results, and much more: for example, personalisation app Google Now seeks to “give you the information you need throughout your day, before you even ask”. Such personalisation systems don’t just aim to provide relevance to users; through targeted marketing strategies, they also generate profit for many free-to-use web services.

Perhaps the best-known critique of this process is the “filter bubble” theory. Proposed by internet activist Eli Pariser, this theory suggests that personalisation can detrimentally affect web users’ experiences. Instead of being exposed to universal, diverse content, users are algorithmically delivered material that matches their pre-existing, self-affirming viewpoints. The filter bubble therefore poses a problem for democratic engagement: by restricting access to challenging and diverse points of view, users are unable to participate in collective and informed debate.

Attempts to find evidence of the filter bubble have produced mixed results. Some studies have shown that personalisation can indeed lead to a “myopic” view of a topic; other studies have found that in different contexts, personalisation can actually help users discover common and diverse content. My research suggests that personalisation does not just affect how we see the world, but how we view ourselves. What’s more, the influence of personalisation on our identities may not be due to filter bubbles of consumption, but because in some instances online personalisation is not very “personal” at all.

Data tracking and user pre-emption

To understand this, it is useful to consider how online personalisation is achieved. Although personalisation systems track our individual web movements, they are not designed to “know” or identify us as individuals. Instead, these systems collate users’ real-time movements and habits into mass data sets, and look for patterns and correlations between users’ movements. The found patterns and correlations are then translated back into identity categories that we might recognise (such as age, gender, language and interests) and that we might fit into. By looking for mass patterns in order to deliver personally relevant content, personalisation is in fact based on a rather impersonal process.

When the filter bubble theory first emerged in 2011, Pariser argued that one of the biggest problems with personalisation was that users did not know it was happening. Nowadays, despite objections to data tracking, many users are aware that they are being tracked in exchange for use of free services, and that this tracking is used for forms of personalisation. Far less clear, however, are the specifics of what is being personalised for us, how and when.

Data gathering: less complex than we might think. Anton Balazh/Shutterstock

Finding the ‘personal’

My research suggests that some users assume their experiences are being personalised to complex degrees. In an in-depth qualitative study of 36 web users, upon seeing advertising for weight loss products on Facebook some female users reported that they assumed that Facebook had profiled them as overweight or fitness-oriented. In fact, these weight loss ads were delivered generically to women aged 24-30. However, because users can be unaware of the impersonal nature of some personalisation systems, such targeted ads can have a detrimental impact on how these users view themselves: to put it crudely, they must be overweight, because Facebook tells them they are.

It’s not just targeted advertising that can have this impact: in an ethnographic and longitudinal study conducted of a handful of 18 and 19-year-old Google Now users, I found that some participants assumed the app was capable of personalisation to an extraordinarily complex extent. Users reported that they believed Google Now showed them stocks information because Google knew their parents were stockholders, or that Google (wrongly) pre-empted a “commute” to “work” because participants had once lied about being over school age on their YouTube accounts. It goes without saying that this small-scale study does not represent the engagements of all Google Now users: but it does suggest that for these individuals, the predictive promises of Google Now were almost infallible.

Are you an ideal user? EPA/DANIEL DEME

In fact, critiques of user-centred design suggest that the reality of Google’s inferences is much more impersonal: Google Now assumes that its “ideal user” does – or at least should – have an interest in stocks, and that all users are workers who commute. Such critiques highlight that it is these assumptions which largely structure Google’s personalisation framework (for example through the app’s adherence to predefined “card” categories such as “Sports”, which during my study only allowed users to ‘follow’ men’s rather than women’s UK football clubs). However, rather than questioning the app’s assumptions, my study suggests that participants placed themselves outside the expected norm: they trusted Google to tell them what their personal experiences should look like.

Though these might seem like extreme examples of impersonal algorithmic inference and user assumption, the fact that we cannot be sure what is being personalised, when or how are more common problems. To me, these user testimonies highlight that the tailoring of online content has implications beyond the fact that it might be detrimental for democracy. They suggest that unless we begin to understand that personalisation can at times operate via highly impersonal frameworks, we may be putting too much faith in personalisation to tell us how we should behave, and who we should be, rather than vice versa.

Author: Tanya Kant, Lecturer in Media and Cultural Studies, University of Sussex

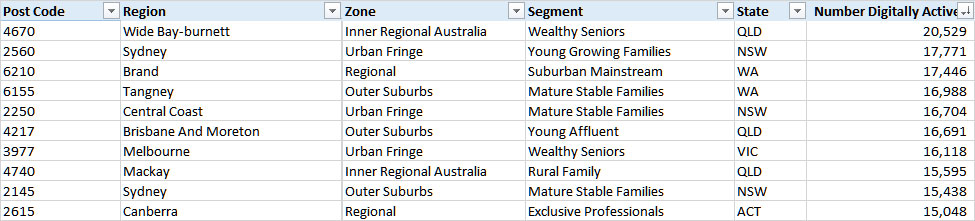

We finish our review of the top digital suburbs across Australia by revealing the top ten post codes with the highest counts of households who are digitally inclined.

This is an interesting list because it consists of a wide spread of household segments, locations and states. This means that counter to the initial idea of a standardised “digital first” approach, effective digital strategy needs to be tailored and targetted to each group. Segmentation is still required.

This is an interesting list because it consists of a wide spread of household segments, locations and states. This means that counter to the initial idea of a standardised “digital first” approach, effective digital strategy needs to be tailored and targetted to each group. Segmentation is still required.

The truth is that effective digital strategy still requires intimate knoweldge of the target groups. This is something which can be done more easily via digital channels, if the strategy is built correctly. However, many players are yet to harness the potential this offers, and to appreciate the full implications for those with a strong physical geographic footprint.

Read more about “digital first” in our report – The Quiet Revolution.

According to Computerworld, Financial institutions that fail to make their APIs openly available are “doomed”, says Visa’s ANZ head of product Rob Walls.

“Anyone that stands still in the current environment of technology change is doomed. We have to continue to evolve – because consumers are expecting it,” he said.

In February, the payments giant published more than 40 APIs “for every payment need” on its Visa Developer platform. The web portal also provides access to sandboxes, documentation and test data.

“We came to the view that there isn’t a single entity that can own all of the innovation in payments,” Walls said. “We’ve been operating as a payment network for almost 60 years. Previously our network was fairly closed, only those who were financial institutions or merchants or tech companies, that were authorised to access it, were able to engage with us.

“Over the past couple of years we’ve seen disruption in many industries, we’ve seen organisations change the way they’re using technology. With with millions of developers around the world today, which is forecast to grow, the value really is going to come from co-creation.”

Walls said that there were around 140 services within Visa that could be made available and there was a push internally to post more.

“There’s now a bit of internal competition around how quickly can I get my product or service into the API set. You want more people using it.”

APIs already published were selected based on client demand and the ease at which they could be securely extracted and made available for external consumption, Walls said.

Australian financial bodies have been cautious in making APIs openly available, citing cost and security concerns.

The situation is a source of frustration for local startups and fintech companies. In a submission to the Productivity Commission – currently conducting an inquiry into improving the availability and use of public and private sector data including open banking APIs – industry association Fintech Australia said failing to mandate open data would make Australia less competitive on the global stage.

“If Australia does not mandate an Open Financial Data model that is in line with global standards, or leaves banks to implement Open Banking APIs at their own pace, we will deny consumers the benefits of greater competition and improved financial services, and risk our banks becoming less agile and less competitive than their international peers,” the peak body wrote.

European regulation – the Payment Services Directive (PSD2) – requires that EU banks make it easier to share customer transaction and account data with third-party providers. Last year the UK government established the Open Banking Working Group with a remit to design a framework for an open API standard.

Open minds

Financial institutions were increasingly coming round to the potential of sharing APIs and drawing on the developer community, Walls said.

ANZ bank has made a limited number available via its Developer Hub and CIO Scott Collary announced in July that: “We want to be a more open bank”. NAB ran a hackathon at the end of last year, with monitored access to a number of its APIs.

“I think what’s really driving it is the fear of disruption. But that language is changing amongst financial institutions in Australia. Instead of being disrupted how can we work with the disruptors to improve the overall service?” Walls said

“The banks and Visa are of the view that innovation is able to come from anywhere and if it’s able to be integrated into my business in a fast, simple, viable way – then I don’t necessarily have to build it.”

Later this month, Aussie and Kiwi start-ups will pitch business ideas that make use of Visa services in a competition, ‘The Everywhere Initiative’.

Successful startups that can develop innovative applications using Visa APIs ‘to solve business challenges and bring new ideas to payments’ in three categories stand to win cash prizes and the chance to run a pilot with Visa.

Businesses seem obsessed these days with getting you to “like” them on Facebook.

It’s difficult to browse the internet without being inundated with requests to like a company’s Facebook page or with contests and offers dependent on doing so.

From the company’s perspective, a like on Facebook offers a chance to stay “top of mind,” a marketing concept that means a consumer thinks of a specific brand first for a certain product or service by having its promotional messages show up in that user’s Facebook newsfeed. Being liked can also be used as a metric to determine the performance of social media campaigns and other promotional activities. The more a company is liked, the more successful the promotion is thought to be.

But is this really the case? To find out, we surveyed hundreds of Facebook users to dig into the meaning and value of the Facebook like. We wanted to understand the motivations behind liking certain types of brands and discover how that affects interactions between the user and the business. We also sought to understand how this varies depending on brand type (i.e., product makers versus service providers).

Findings from two studies we undertook reveal that what likes say about consumers and what they think about the brands they like is surprisingly varied.

Does Facebook’s ‘like’ button create brand loyalty? Fabrizio Bensch/Reuters

The loyalty of liking

For the first study, we asked 150 Facebook users to tell us about a brand that they currently like on Facebook. We then asked them to describe their motivation behind clicking the like button the first time, their interactions with the brand since liking them and any changes that have occurred in their relationship with the brand since then.

From our results, it seems that the primary reason that consumers choose to like a brand on Facebook is a sense of existing loyalty or obligation to support a brand. The largest percentage of respondents said they liked a brand simply because they felt that’s what a loyal fan should do. The next biggest share seemed to be more focused on getting something in return for their like, such as information, social recognition or entries into contests.

Interestingly, only a relatively small percentage of respondents reported that they “liked” the brand on Facebook because they simply liked (had a positive attitude toward) the brand. This differs from loyalty in subtle ways.

For example, I may have a positive attitude toward the Rolls Royce brand after seeing its products in advertisements, product placements, etc., but I have never owned one of its cars; therefore, I do not feel loyalty or obligation to the brand. This finding shows that some users who may not have purchased products from the brand may still like the brand on Facebook for various reasons.

As for levels of interaction since first liking a brand, over half of users said that while they may have read the brand’s posts or viewed its images in their Facebook newsfeed, they haven’t given any information whatsoever back to the brand. Just one-fifth said they reposted or shared content from the brand, while only 17 percent reported actually commenting on brand posts.

Finally, there was an interesting and contradictory set of instances in which respondents reported no change in the brand relationship but at the same time went on to actually detail positive brand-related consequences.

For example, a respondent initially noted that his relationship with Ford did not change after liking the Ford page, but later noted that he did look at more photos of new Ford trucks posted by the company on Facebook. This could be interpreted as a change in their relationship, because they are interacting more with the brand.

This suggests that generating Facebook likes can indeed have positive outcomes for a company, including having more interaction with its fans.

Are all likes created equal?

While the first study provided interesting results, we wanted to see if there was a statistically significant difference in the way that Facebook users reported interacting with product versus service brands.

While varying types of businesses may all be trying to gain the same outcome, there is evidence that differences exist between how product- and service-based brands interact with potential customers, ones that require distinct engagement strategies.

Just as all brands are not the same, all likes are not equal. It may seem more natural to like a brand that makes an actual product such as a favorite car manufacturer or clothing brand than a service like a plumber, cable provider or pet groomer. That’s because, due to their intangible nature, services can be much more difficult for consumers to evaluate. As a result, service companies need to initiate social interactions with their customers in order to communicate value and set appropriate expectations.

So in our second study, we surveyed 300 Facebook users to explore these differences and discovered some interesting similarities and differences in the way they interact with brands selling products and those offering services.

For example, we found that “fans” of product brands were more likely to report engaging in passive interactions with the company such as by reading or liking posts compared with those of service brands. They also reported a greater intention to make future purchases.

We found no differences between the groups, however, in their intentions to engage in more active Facebook interactions such as sharing or commenting on posts.

Parsing the results

So what does this all mean?

First, it tells us that simply adding up Facebook likes does not necessarily tell us how engaged a customer is with a company’s brand. Many of our respondents liked their respective brands for reasons other than wanting to engage in an interactive relationship. In other words, quantity of likes does not equal quality of relationships.

In addition, brand and social media managers should not automatically assume that new Facebook followers are new to the company. Many of our respondents felt that it was their obligation to a favorite or oft-purchased brand to like that brand on Facebook.

Although passive engagement with followers is perhaps not what gets the most attention when pundits discuss the benefits of Facebook engagement, it still offers benefits, such as becoming more “top of mind.” Brand managers should not always assume that their loudest and most active Facebook followers are the only ones getting the message.

Finally, our research offers different lessons for service- and product-based brands. For the former, feelings of brand connectedness were a strong outcome of Facebook interaction. These companies should perhaps focus more on personalizing their Facebook messages in an attempt to further stimulate and enhance this elevated sense of connectedness.

For product-based brands, although brand connectedness was lower, purchase intention and brand attitude – the positive or negative associations one has with the brand – were higher. To leverage this, these companies should perhaps include more calls to action on Facebook and showcase their latest and greatest product offerings.

So next time you “like” a brand on Facebook, think about what you are telling the company. And whether that’s the message you want to send.