For their iOS 9 release, Apple not only permits, but actively encourages developers to make Apps that remove advertising and tracking from the web. They added this feature deliberately; it’s not a hack by developers they’ve turned a blind eye to.

HOW EFFECTIVE ARE MOBILE AD BLOCKERS

I’ve been using two Apps called Adblock Fast and Crystal for the past week and surfing the web on my iPhone has become delightfully fast and uncluttered. Blocking ads on your mobile phone is like moving from a crowded apartment complex in a polluted, violent city to a peaceful lake house.

It’s a massive, noticeable change for two important reasons that have to do with the device you’re holding: screen size and bandwidth.

Given the increasing size of our desktop monitors, multiple windows to choose from, and increasingly fast cable modems and fiber connections, ad blockers have been a minor innovation on the desktop this past decade. (We hate you if you have fiber, really.) On a desktop, you barely notice the ads are gone, because the ads weren’t laying on top of the content. They were typically around the content.

On an iPhone, well, you’re dealing with 5-10% of the screen size of your desktop monitors, so publishers putting up a roadblock on the content, then asking you to use your fat fingers to hit the tiny little X or ‘skip the ad in 4… 3… 2… 1…’ is just overbearing.

Mobile advertising is so ugly and intrusive, it actually makes people AVOID mobile browsing. That’s why the ‘read it later’ feature, pioneered by Marco Arment’s brilliant Instapaper and Nate Weiner’s Pocket, became so popular that Apple copied them. When a user hits ‘read it later,’ it means ‘read this when I don’t have to deal with all this bullshit.’

APPLE’S MOTIVATION IS MARGIN

Apple doesn’t give an ‘ish about advertising, unless of course they’re buying it for their award-winning TV commercials. (More on that later.) Apple cares only about you loving and using the product that now generates nearly 70% of their (top-line) revenue – and perhaps even MORE of their (bottom-line) profits – the iPhone.

The iPhone is everything to Apple. Everything important about Apple – their resurgence as a company, the lust their fans feel for the brand, the fanboy/girl obsession with their keynotes, the slavish CNBC analysis over everything Tim Cook says – traces back to the luscious, warm-gravy margins of the iPhone.

For every 1% in smartphone marketshare Apple converts, they make another $10b a year in revenue*, and Apple very much thinks that they can convince the world to convert from cheap phones to the more expensive iPhone.

[ * back of envelope: 1.44b smartphones will ship in 2015, 1% = 14m iPhones * ~$658 average revenue per unit = $9.5b ]

And they’re right.

Life is better in Apple’s world.

WHY LARRY LEFT GOOGLE

Google is assaulting us with advertising to the point that the FTC and EU want to sanction them (in fact, the WSJ reported that, magically, the FTC’s action against Google was killed – conspiracy theories abound).

What is not up for debate is that Google is ripping away our privacy every day, taking the most intimate pieces of our lives and selling them in buckets of parts – like pieces of cow flesh in a Whole Foods display case.

Google makes a massive portion of their money, according to studies, getting people to accidentally click on ads (40% of people don’t know Google Ads are ads). Ads that are taking up the top 11 of 13 search results on some search pages.

Google kept heating up the water until they accidentally boiled the frog. And the frog is us.

Apple knows it and they’re assaulting Google on every front. Ad-blocking is the attack we are talking about today, but privacy is another and their wildly-improving, hiding-in-plain-sight search engine is yet another. I wrote about this search engine back in June 2015, and I will do a Part 2 of this piece if someone reminds me and I actually get some sleep this week. (I got some life-changing, big news last week and I’m not sleeping well … I’ll disclose it when Gayle King interviews me about “having it all.”)

Google knows what’s up, and that’s why Larry gave himself a promotion to CEO of Alphabet.

Larry doesn’t want his legacy to be grinding every last percentage point out of their advertising network. Sergey doesn’t want folks coming up to him at parties and asking him about why they are trying to kill Yelp, Mahalo, and eHow (trust me, I have the inside line on this one).

Nope, like the Middle Eastern sovereign wealth fund I met with yesterday, Google is trying to trade their oil money for something more refined, like self-driving cars, life extension (Calico) or home automation (Nest).

Google wants to be proud of their legacy, and tricking people into clicking ads and selling our profiles to advertisers is an awesome business – but a horrible legacy for Larry and Sergey.

[ Side note: When I asked the Sovereign wealth fund why they were bothering to meet with me, when they had billions of dollars to put to work and I angel invest $100,000 at a time, they said they were rebalancing their oil to tech and they needed to meet with the ‘mother of unicorns.’ I think that makes me Khaleesi? That’s kind of awesome. ]

IS IT MORAL FOR APPLE TO BLOCK ADS?

It’s your device, so you can do whatever you want with it. When you download something onto your device, it is now yours to remix and play with in any way you want – provided you don’t republish it and make money from it. (Fair use is the exception here.)

According to this basic tenet, if I buy the New York Times in print, clip out all the ads and then tape it back together at home, well, that’s my right.

Now, Apple didn’t just bake ad blocking into the browser. They enabled developers to add ad blockers – via the App store – to consumers’ browsers. In this way, you still have to buy the scissors and clip the ads, but that takes under five seconds and will be enabled for the rest of your life.

Apple could, and would, be sued by publishers if they enabled it themselves.

They would be sued, in all likelihood, for breaking the publishers’ Terms of Service, or perhaps better stated, for helping users to break the Terms of Service. This means if you make an App that blocks ads, be ready for a HUGE lawsuit. It will happen if these things hit scale. Apple might become party to these lawsuits for contributing to the interference of a company’s ability to do commerce. The side argument will be, as I’ve outlined in this post, that Apple and the ad blocker companies are benefiting unfairly on the publishers’ backs – consider this piece an amicus brief.

I’m not sure any of these legal concepts would actually work, but Google and publishers will put up a united front against ad blocking if it becomes > 25% of mobile users – of that you can be sure.

Is it moral for Apple to screw publishers? Wow, that’s a big question, but in a nutshell, this is business and it’s not personal. Apple wants to make consumers buy iPhones and use them and blocking ads will help them beat Android.

Apple’s highest moral commitment is to users – not publishers. So, although Apple covets content creators, it doesn’t put their need to make a few shekles above a user’s ability to enjoy the experience of the iPhone.

Apple really wants publishers to charge for content and take 30% through the App store and their marketplaces. People who work at Apple are rich, so they don’t really get the concept of not being able to afford to pay for content.

It’s classist, to be sure. Just like the margins on iPhones make them hard for poor people to embrace them. Then again, if you look at the cost of a new iPhone phone every 30 months, it’s around $20 a month (say $650 with a $50 trade in of your old phone).

If an Android phone was half the cost of an iPhone, the cost difference is $10 a month – or about one hour of work for the lowest paid folks in the United States.

One extra hour of work a month to own the best device as your PRIMARY consumption device in the world IS A BARGAIN.

Tim Cook knows this and he is watching as the poor people of the world figure it out. Apple’s message is the same as Starbucks: treat yourself poor people, you deserve it!

And they’re right! Why shouldn’t the housekeeper, gardener, or teenager spend just $0.35 a day to have the better phone if they use it three or four hours a day?

Back to stealing.

Would Apple allow you to put a bittorrent App on your phone and download TV shows and series, instead of paying for content in iTunes? Well, we actually know the answer to that question – hell no!

Apple draws the line at stealing content, and doesn’t see the subversion of ads as stealing – which all of us in the real world know it is. Undermining a publisher’s ability to monetize is stealing, but it’s Robin-Hood, feel-good stealing.

So killing advertising not only crushes Google, it also could flip many publishers from ad-driven models to subscriptions … in Apple’s App store.

Oh yeah, Apple launched a News App as part of iOS 9, too.

That’s interesting timing. I wonder if Apple will launch a ‘pay $10 a month for 500 newspapers/magazines’ subscription and share that revenue with those publishers based on some slick algorithm. (Consumption + a base payment for everyone.)

Apple will make their News App the Spotify of Content … giving every publisher a basic income based on the profits of the iPhone ecosystem. In fact, Google bought Oyster which was the “Netflix of books.” The idea of a big company providing all-you-can-eat for a monthly price is coming soon, you can be sure of that.

In Conclusion

Publishers are screwed.

Google is really screwed.

Consumers win.

Apple really wins.

Now, will consumers ultimately lose because publishers go out of business? That’s the obvious question … with the obvious answer: we’re gonna find out next year.

One thing you can count on: Apple has a Master Plan around privacy, saving the news business, doubling iPhone market share and killing Google for double-crossing Steve Jobs.

Never forget what Steve Jobs said:

“I will spend my last dying breath if I need to, and I will spend every penny of Apple’s $40 billion in the bank, to right this wrong. I’m going to destroy Android, because it’s a stolen product. I’m willing to go thermonuclear war on this.” – Steve Jobs to Walter Isaacson in 2010.

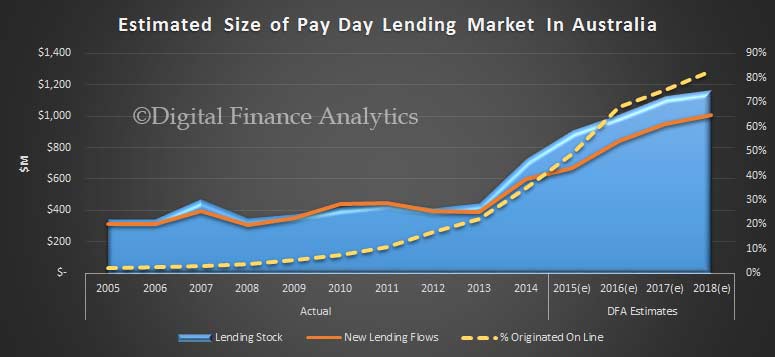

The transference to online channels is linked with a rise in the number of households who, whilst not financially distressed (distressed households are first not meeting their financial commitments as they fall due, and are also exhibiting chronic repeat behaviour, and have limited financial resources available) are financially stressed (struggling to manage their financial affairs, behind with loan repayments, in mortgage stress, etc).

The transference to online channels is linked with a rise in the number of households who, whilst not financially distressed (distressed households are first not meeting their financial commitments as they fall due, and are also exhibiting chronic repeat behaviour, and have limited financial resources available) are financially stressed (struggling to manage their financial affairs, behind with loan repayments, in mortgage stress, etc).