Every now and then, I see an article in the media that is skeptical about the future of mobile advertising – the kind of ad you see when you open an app on your smartphone and there’s either a discount coupon at the center of the screen or a display ad at the bottom.

Many critics have asserted that mobile advertising does not work, that mobile marketing is all but dead and that people worry too much about their data privacy to accept these techniques on their devices and will not do so in the future.

Facebook’s latest quarterly earnings report may show that the social media network now earns a whopping 75% of its US$12.5 billion in annual revenue from mobile advertising, but even that does not seem to calm the naysayers.

Now the skeptics may start changing their minds, however, thanks to a number of recent rigorous studies that have systematically analyzed the effectiveness of different kinds of mobile advertising and marketing over the past few years in a wide variety of countries.

Using carefully designed field experiments, my colleagues, fellow scholars and I have consistently found irrefutable evidence that mobile advertising works.

More importantly, we have seen that 85% of users have willingly embraced the idea that marketers will reach them with an offer for the right product at the right time at the right place on the right device (smartphone). In fact, 49% of users are receptive to it and willingly sacrifice data privacy in exchange.

The question isn’t whether mobile advertising is effective, as I’ll show; it’s what factors make it more or less effective and make it more likely that a consumer will engage.

It turns out that various factors – such as location, time, weather and crowdedness – influence the effectiveness of mobile advertising, especially when done in the form of coupons.

A complex infrastructure

At the outset, it is useful to distinguish between mobile push advertising (a coupon sent in a text message) and pull advertising (an offer or message in an app such as Yelp).

From a functional perspective, pull advertising is similar to search engine advertising by presenting consumers with a list of coupons that are sorted by relevance in terms of location, prices or store ratings, allowing them to actively search for preferred options.

Conversely, the concept of mobile push advertising is more closely related to display advertising, in which users are either being targeted depending on their browsing behavior (behavioral targeting) or by the context of the website (contextual targeting).

Mobile ads work

A number of studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of mobile advertising in different contexts.

For example, Professor Yakov Bart and colleagues have shown that mobile display ad campaigns significantly increased consumers’ favorable attitudes and purchase intentions when they promoted products that were utilitarian (ie, need-based goods used for practical purposes) versus hedonic (ie, desirable goods that are used for luxury purposes). Similarly, Professor Sam Hui and colleagues have shown that targeted mobile promotions that incentivize people to travel more within a store can increase unplanned spending by as much as $21 per visit.

Studies by mobile app analytics companies like Flurry have shown that people are more than willing to tolerate ads and accept various forms of mobile marketing in exchange for cool apps. While consumers may not be in love with in-app advertising, their behavior makes it clear that they are willing to accept it in exchange for free content, just as we have on the internet for years.

The impact of geography, time, weather and context

Lets start with geography. In today’s location services-enabled smartphones, it is intuitive to expect that geographical targeting can increase product sales or at least brand affinity.

Research I conducted with my coauthors (Avi Goldfarb and Sangpil Han) in 2013 demonstrated that even when users interact with brands on social media platforms like Twitter, they tend to engage much more strongly with brands whose stores are in close proximity to where they are physically located at any given point in time.

In another separate study, my coauthors (Dominik Molitor, Martin Spann and Philipp Reichart) and I showed that the farther away from a store a user is when receiving a coupon, the less likely it will be redeemed. Increasing the distance to a store by one kilometer (0.62 miles) decreases mobile coupon response rates by between 2% and 4.7%.

It is also intuitive to expect that temporal targeting – the time a user is sent a certain type of ad – matters.

For example, sending a mobile coupon for a 50% discount on a beer on a Tuesday afternoon at 2 pm has a much lower probability of being redeemed than a 50% offer on a cappuccino at the same time and same location, after controlling for price.

Surprisingly, the sales impact of employing these two strategies (location and time) simultaneously is not straightforward.

A paper by Temple University scholar Xueming Luo and others draws on contextual marketing theory to show that when targeting proximal mobile users – those located near an event or store – the odds of a sale are higher by 76% for a same-day promotion compared with sending a promotion two days in advance.

By contrast, with non-proximal mobile users, they found that a little advance notice helped, but not too much. When a mobile coupon is sent out one day ahead of an event, the odds of a consumer purchase jumps 950% compared with a same-day text message and 71% compared with one sent two days ahead of time.

Basically, consumers who received marketing messages close to the time and location of an event formed more concrete mental construals – a term in social psychology referring to how individuals perceive, comprehend and interpret the world around them. That in turn increased their involvement and purchase intent, while more spatial and temporal distance had the opposite effect.

Even weather can impact the effectiveness of mobile advertising.

A 2015 study revealed how mobile purchases prompted by marketing were significantly higher on days with more sunshine and lower when it was cloudy or rained. Theories from psychology have argued better weather, both actual and perceived, induces better moods and causes an increase in risk tolerance or the willingness to part with cash. On the other hand, exposure to bad weather leads to poor moods and more risk aversion.

Finally, it turns out that our propensity to respond to mobile advertising is also affected by how crowded our environment is.

In a 2014 paper my coauthors (Michelle Andrews, Xueming Luo and Zheng Fang) and I showed that people are more likely to redeem mobile coupons when they are being physically squeezed in crowded contexts.

Based on a follow-up user survey that we carried out, this behavior can be explained by the phenomenon of ”mobile immersion”: to psychologically cope with the loss of personal space in crowded contexts, users can escape into their personal mobile space. Once there, they become more involved with the targeted mobile messages they receive, and, consequently, are more likely to make a purchase in crowded contexts.

For marketers, the high-level finding is that consumers may be more receptive to targeted mobile ads when they are in crowded spaces with strangers, whether in a subway car or even in a busy tourist area such as New York City’s Times Square.

Lip service to privacy

Here is the bottom line: we think we care about data privacy, but when it comes to redeeming offers on our smartphones, we actually pay it only lip service.

Put differently, an increasing proportion of people (especially millennials) understand that a give-and-take relationship is becoming more common as we interact with brands trying to sell us stuff.

We give our data to marketers (both willingly and inadvertently), and in return we expect to receive highly curated and personalized offers on our smartphones. Many consumers have even become resigned to the idea that they have little control over their data, and that this is the future of the world we will inhabit.

Does every form of mobile advertising work well? Of course not.

A banner ad that pops up and covers the already scarce real estate on our screen is not going to be nearly as well-received by users as an offer distributed via text message and triggered by a location-sensing beacon when we are up and about in a shopping mall.

For example, as you walk past Zara, your smartphone buzzes with an offer of 15% off any purchase from Zara and a 20% off any purchase from American Apparel. In our most recent paper, my coauthors (Beibei Li and Siyuan Liu) and I showed that consumers have a growing preference for these kinds of offline trajectory-based mobile advertising: they are yielding extraordinary high redemption rates and customer satisfaction rates.

There is a simple message for mobile marketers in all of this: consumers appreciate relevancy and context. So make that ad count. Work on your targeting. Don’t overwhelm us with too many notifications. Don’t abuse our trust.

The evidence clearly shows mobile ads are not going anywhere. As such, the future of mobile advertising looks incredibly bright to me.

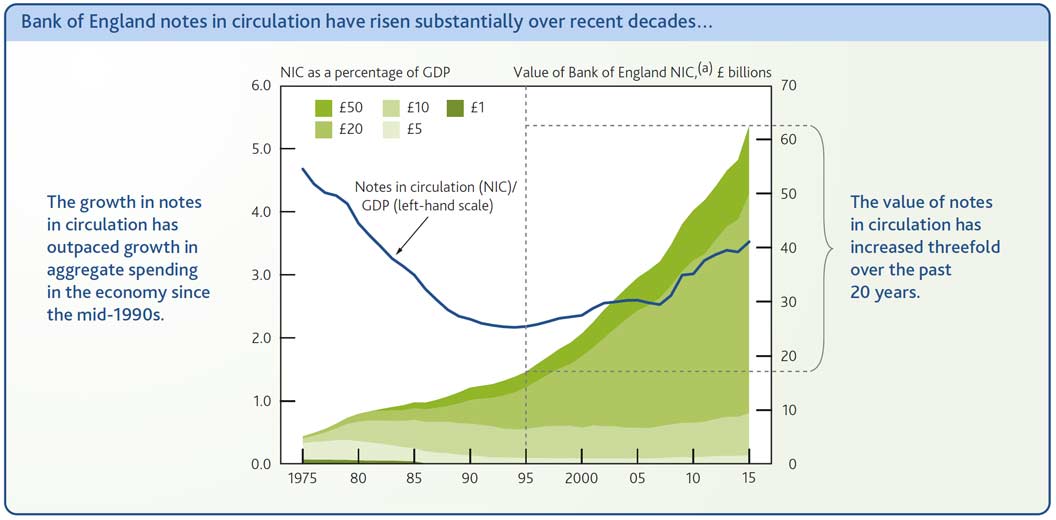

There is now the equivalent of around £1,000 in banknotes in circulation for each person in the United Kingdom.

There is now the equivalent of around £1,000 in banknotes in circulation for each person in the United Kingdom.