Australia’s economy grew by just 0.2% in the June quarter, below expectations of 0.4%, largely as a result of reduced mining and construction activity and a decline in exports of 3% during the quarter.

Nominal Gross Domestic Product grew by 1.8% during the year, which the Australian Bureau of Statistics said was “the weakest growth in nominal GDP since 1961-62”. Despite this, Australia has now recorded 24 straight years of growth.

The news has some analysts and economists spooked, and politicians blaming each other for the slowdown.

Treasurer Joe Hockey said:

At a time when other commodity based economies like Canada and Brazil are in recession, the Australian economy is continuing to grow at a rate that meets and sometimes beats our most recent budget forecasts.

He also said it was “factually wrong” to say it was the weakest growth since 1961.

The fact is that the economic growth we had in the last quarter was in line with expectations. Of course it bounces around from quarter to quarter, but it was in line with our overarching expectation to have two and a half per cent growth in the last financial year.

Shadow Treasurer Chris Bowen said:

Growth has flat-lined since the Abbott government’s first damaging budget last year and cost of living pressures are continuing to increase. This is the biggest quarterly decline in living standards since the global financial crisis.

This is a very weak set of figures and for the government to cast around for international comparisons to try and make it sound better is a pretty pathetic excuse.

The Treasurer says Australia is still doing better than Canada, Brazil, the US and New Zealand. How should people view these numbers in a global context? To what extent is the slowing rate of growth due to global economic headwinds, and to what extent is it due to domestic factors?

Griffith Business School Professor Fabrizio Carmignani answers:

In the past, the Australian economy has proved to be quite resilient to global economic shocks. Today we are facing what could be potentially a perfect storm.

For one thing, international commodities prices are very volatile and have resulted in a sharp contraction of Australian’s terms of trade. For another, China is going through a complicated economic phase and it is not, at this moment, the same solid anchor for the Australian economy as it might have been previously. So, it is not surprising to see that on a seasonally adjusted basis, quarterly growth in Australia has been oscillating between 0.2% and 0.3% for the last five quarters.

We owe it to some good old Keynesian stimulus on the demand side (read: government consumption and to a lesser extent public gross fixed capital formation) if we are not entering a technical recession.

The comparison with Canada, on surface, is favourable to Australia. Canada has officially entered a recession after recording two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth in the first half of 2015. This is essentially due to low oil prices. However, according to media reports, Canada is still committed to achieving a target of annual growth of 2.5% this year, which is exactly what the Treasurer has stated for Australia. So, it seems to me that the difference between Australia and Canada here is thinner that what might appear at first sight. A fraction of a percentage point below or above the zero growth line is not really indicative of substantially different structural positions.

Both Australia and Canada are facing similar challenges in terms of diversification. The current “crisis” to me shows that these challenges are still far from being fully addressed in both countries.

Australia has had 24 years of consistent growth. How much of this can we attribute to the mining boom? And given the cyclical nature of the economy, can we expect a downturn?

Griffith University Professor Tony Makin answers:

Australia has performed relatively well compared to other OECD economies over recent decades, though did actually experience a recession during the GFC according to income and production measures of GDP.

Taking population growth into account, Australia’s economic performance since the global financial crisis has been worse than the raw GDP numbers show. On a per capita basis, national income has grown on average below one per cent per annum, less than half the almost two and a half per cent per head per annum average rate in the decade before the GFC.

The extraordinary boost to the terms of trade from the world commodity price hike, especially between 2005 and 2011, substantially raised Australia’s international purchasing power. However, GDP growth during the mining boom was actually less than during the economic reform era from the mid-1980s through to the end of the 1990s when commodity prices were fairly flat.

The main culprit for Australia’s sub-normal economic growth in recent years has not been falling commodity prices, which have undoubtedly played a role, but Australia’s underlying competitiveness problem, combined with a productivity slowdown that began from the turn of the century.

While the recent depreciation of the dollar will go some way to restoring Australia’s competitiveness and help stave off recession, genuine productivity-enhancing reform focusing on the economy’s supply side remains as important as ever for returning GDP and income per head growth to long-term average rates.

One journalist at Wednesday’s press conference said the new data showed “the weakest growth since 1961”, but the Treasurer said that was factually wrong. Who is right?

UNSW Australia Professor Richard Holden answers:

The statement that it is the slowest growth since 1961 seems, to me, to be false. We have had recessions in the 1990s and 1980s, which is two successive quarters of negative growth. And yesterday we had positive growth, so it was a slowdown but not the worst we have seen since 1961. I think the journalist’s statement doesn’t seem correct to me, on the face of it. I think the Treasurer is right.

It is possible the journalist was referring to the Australian Bureau of Statistics comment yesterday that:

GDP growth for 2014-15 was 2.4%. Nominal GDP growth was 1.8% for the 2014-15 financial year. This is the weakest growth in nominal GDP since 1961-62.

Nominal growth and growth are not quite the same thing. Nominal growth means GDP growth that is not adjusted for inflation.

But yes, yesterday’s numbers are still below projected growth. It is below market expectations. I think the Treasurer saying we have projected 2.5% annual growth this year and this is basically on target is a bit disingenuous. This is slow growth, it’s actually very troubling.

I understand the Treasurer can’t talk down the economy so his comments are understandable and he is in a difficult position. But the low rate of growth is genuine cause for concern.

I have written before about the concept of secular stagnation, which is the idea that growth of advanced economies looks like it has slowed down dramatically. The figures yesterday are further evidence of that theory.

Victoria University Senior Research Fellow Janine Dixon answers:

While it is factually correct that real GDP – the volume of production in the economy – has grown, the low growth in nominal GDP points to an underlying weakness in the economy. This is our exposure to the very large fall in commodity prices. When we translate real GDP into real income, we take into account that fact that the prices of the things we produce for export have fallen relative to the prices of the things we consume, some of which are imported. This has been a very important determinant of real incomes in the last few years.

Real net national disposable income is a better measure of our living standards than GDP. As well as adjusting for prices, we take into account the fact that some of the income generated domestically actually accrues to the rest of the world if the factors of production are foreign owned. We also deduct the value of capital that is “used up” or depreciated during the year.

Real net national disposable income per person has now fallen for 14 quarters in a row. This represents the most sustained fall in standards of living in the last 50 years.

What’s especially interesting about this period is that falling incomes have not been associated with falling output or particularly high unemployment. In the 1990-91 recession (the one we had to have) or the early 1980’s, incomes fell, but the solution to the problem was fairly clear. More than 10% of the workforce was unemployed. Fixing unemployment would boost production, incomes and living standards.

This time around, incomes are falling because commodity prices are falling. Commodity prices, set on world markets, are largely out of our hands. The labour market is much more flexible these days, and unemployment is 6%, not 10%. We are left with just one way to turn things around. In the words of Nobel laureate Paul Krugman, “Productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run it is almost everything”.

Is GDP really in line with expectations, both of the government and the market?

Griffith University Professor Ross Guest answers:

These GDP expectations are continuously being revised down as new information comes to hand.

The projected growth is lower than nearly everybody expected and everybody is having to revise downward their expectation.

What will the slowing annual growth mean for the federal budget, which had forecast growth for 2015-16 of 2.75%?

Ross Guest answers:

If growth were to remain at its current level of 2%, the budget deficit would be A$15 billion larger, in ball park terms, than the government projected. To put that in perspective, the total amount we spend on unemployment benefits is A$10 billion.

Australia living standards and the Australian government budget are being hit by a perfect storm of lower commodity prices and lower productivity growth.

Victoria University Senior Research Fellow Janine Dixon answers:

The GDP growth forecast for 2015-16 is fairly subdued at 2.75% and the budget not overly ambitious – a deficit of 2% of GDP. The trouble lies in 2016/17 and beyond, when annual GDP growth is forecast to be above 3%.

Over the next five years a couple of downside risks exist that will make it unlikely that GDP will grow this strongly, and consequently the budget’s return to surplus will be more difficult to achieve.

If the terms of trade fall further than allowed for in the budget forecasts, and if productivity growth remains weak, as it has been in recent years, real national income could be 3% lower than forecast by 2020. Roughly, this means the tax base for the government will be 3% smaller than expected. Rather than having a balanced budget by 2020, we would still be running a deficit, of around 0.75% of GDP or $12 billion in today’s terms.

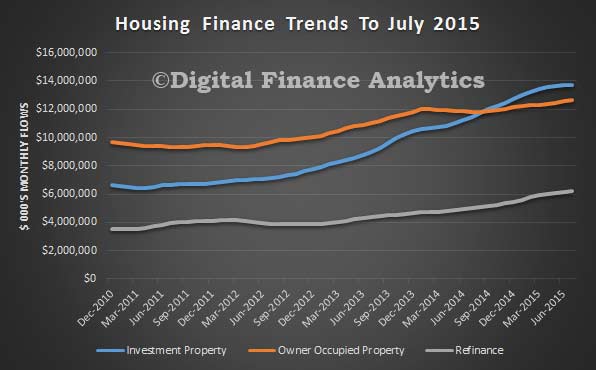

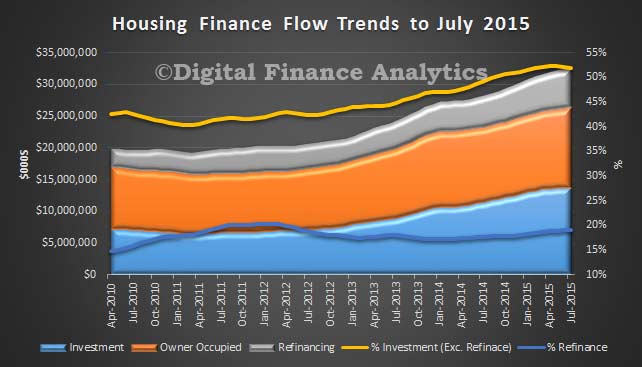

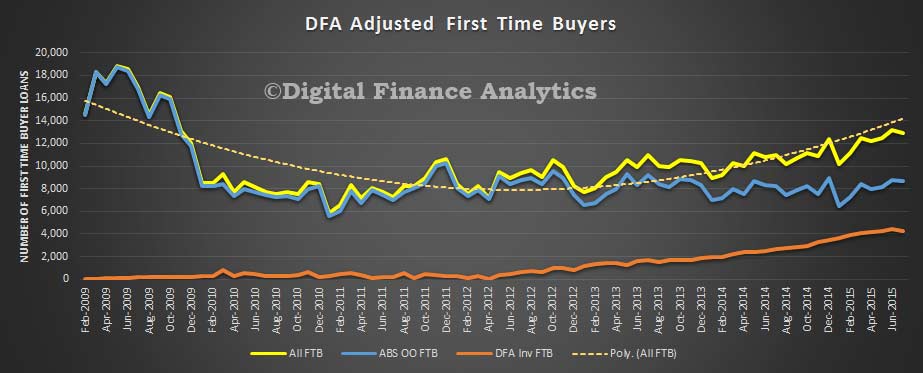

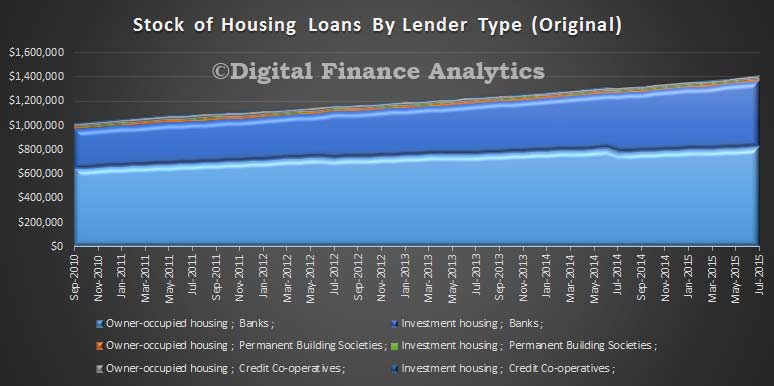

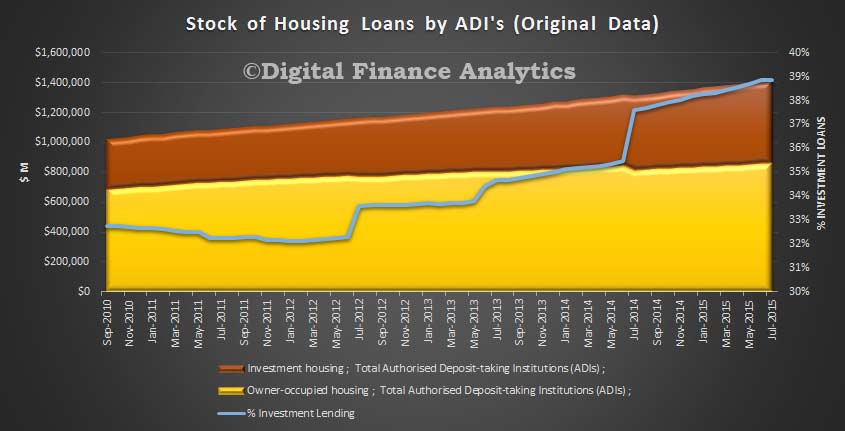

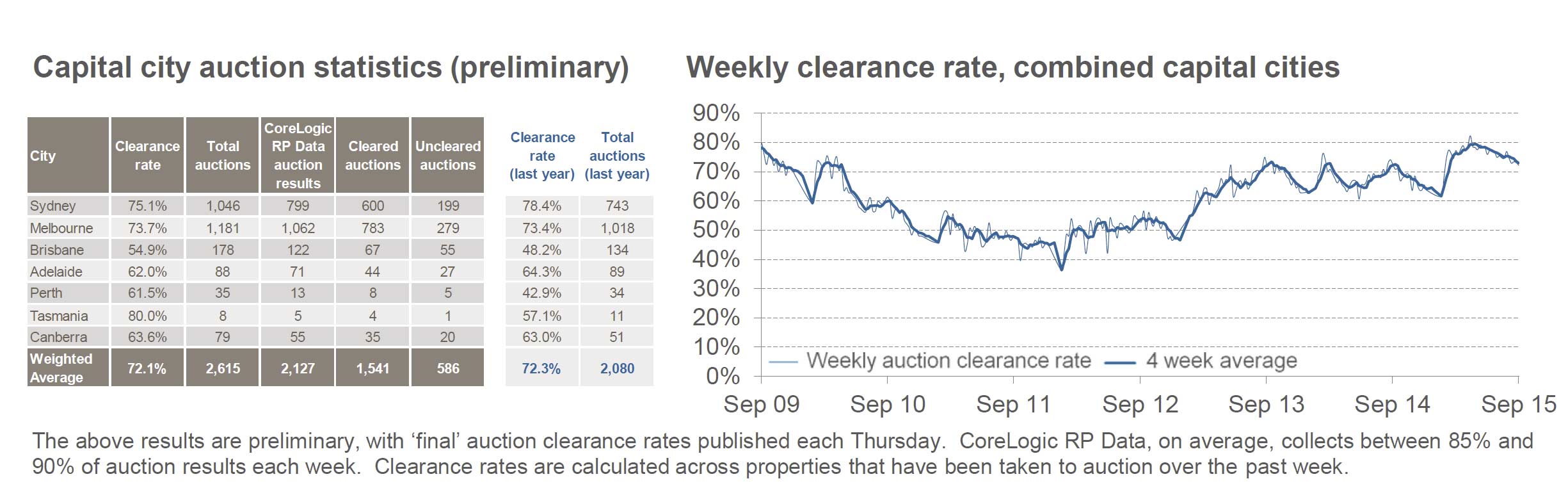

Whilst the combined average house price was up 10.9% in the past 12 months, mortgage application activity appears to be a little lower now.

Whilst the combined average house price was up 10.9% in the past 12 months, mortgage application activity appears to be a little lower now.