The NZ Reserve Bank has published a consultation paper about proposed changes to the rules that banks must follow for high-LVR mortgage loans.

The proposals were announced in the Reserve Bank’s Financial Stability Report released on 13 May 2015. They would mean investors in Auckland property would generally need a 30 percent deposit if they’re borrowing for a property, while home buyers outside Auckland would see increased availability of high-LVR mortgages.

The specific proposals are to:

- Restrict property investment residential mortgage loans in the Auckland region at LVRs of greater than 70 percent to 2 percent of total property investment residential mortgage commitments in Auckland.

- Retain the existing speed limit of 10 percent for other residential mortgage lending, as a proportion of total non-property investment residential mortgage commitments, in the Auckland region at LVRs above 80 percent.

- Increase the speed limit on residential mortgage lending at LVRs above 80 percent outside of Auckland to 15 percent of residential mortgage commitments outside Auckland.

A number of loan categories are exempted from LVR speed limits, and these exemptions will be retained under the proposed policy changes. Specifically, loans that are made as part of Housing New Zealand’s Welcome Home Loan scheme, and loans that are made for the purpose of refinancing an existing mortgage loan, moving house (without increasing borrowing amount), bridging finance or constructing a new dwelling will continue to be exempt from the policy.

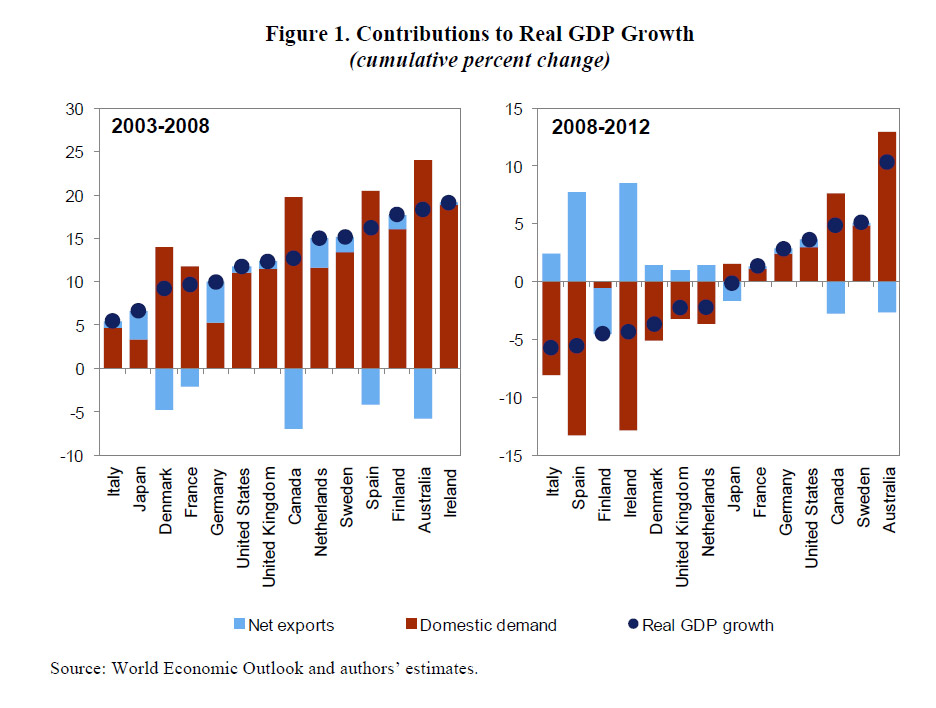

The paper also offers further evidence on the different risk profiles of investment versus owner occupied loans in a down turn, including data from experiences in Ireland.

“Residential property investment loans appear to have relatively low default rates during normal economic circumstances. However, the Reserve Bank has looked at evidence from extreme housing downturns during the GFC, and this clearly indicates that default rates can be higher for investor loans than for owner occupiers in severe downturns. For example, as shown in table 1, forecast loss rates on Irish mortgages were nearly twice as high for investors as for owner-occupiers. Similarly, actual arrears rates were about twice as high for investor loans (29.4 percent) than for owner occupied loans (14.8 percent) as at December 2014. Furthermore, studies which have separately estimated default rates by LVR for investor loans and owner occupier loans suggest that investor loans are substantially riskier at any given LVR. The data shows an estimate of default rate based on current LVR. For example, if a loan was initially written at a 70 percent LVR and then prices fell 30 percent, the loan would appear in the chart below as LTV=100. This would have a mildly increased rate of default compared to a low-LVR loan for an owner occupier. But for an investor, the rate of default would be higher, and would have increased more sharply as a result of a given decline in house prices.”

Note: PDH is principal dwelling house, BTL is buy to let. LTV (loan to value ratio) is conceptually the same as LVR, but this dataset uses the current LTV (after the sharp falls in house prices) rather than origination LTV.

The consultation will run until 13 July. The Reserve Bank expects to publish a summary of submissions and final policy position in August, with revised rules taking effect from 1 October.

The Reserve Bank proposes that the policy changes take effect from 1 October 2015. This relatively long notice period is to allow banks to make the necessary systems changes in order to properly classify new lending. There is a risk that a notice period of this length could lead to some Auckland property investors rushing in to beat the policy changes. However, our expectation is that banks will observe the spirit of the proposed restrictions, and will act to curtail lending at LVRs of above 70 percent to Auckland property investors well in advance of 1 October.

Currently, compliance with the LVR policy is measured over a three-month rolling window for banks with monthly lending of over $100m, and over a six-month rolling window for banks with monthly lending of less than $100m. At the time that LVR restrictions were first introduced, all banks were provided with an initial six-month measurement period. This was done to accommodate outstanding pre-approved loans, and recognised the relatively short notice period provided. A longer first measurement period does not appear to be warranted for this change to the restriction, given more than four months’ notice of an intention to change the restriction. Further, the low speed limit for Auckland property investment mortgage lending does not provide much scope to smooth lending over a longer measurement period.

The reason for this reversal can be explained with respect to a hypothetical $20,000 asset purchased on July 1, 2015, by a small incorporated entity. Under the proposed rules, the company would have reduced its tax payable by $5,700 in the first year, as compared to only $855 under the existing rules.

The reason for this reversal can be explained with respect to a hypothetical $20,000 asset purchased on July 1, 2015, by a small incorporated entity. Under the proposed rules, the company would have reduced its tax payable by $5,700 in the first year, as compared to only $855 under the existing rules.