The Federal Reserve Board has announced it has not objected to the capital plans of 30 bank holding companies participating in the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR). The Board objected to two firms’ plans. One other firm’s plan was not objected to, but the firm is being required to address certain weaknesses and resubmit its plan by the end of 2016.

CCAR, in its sixth year, evaluates the capital planning processes and capital adequacy of the largest U.S.-based bank holding companies, including the firms’ planned capital actions such as dividend payments and share buybacks and issuances. Strong capital levels act as a cushion to absorb losses and help ensure that banking organizations have the ability to lend to households and businesses even in times of stress.

When considering a firm’s capital plan, the Federal Reserve considers both quantitative and qualitative factors. Quantitative factors include a firm’s projected capital ratios under a hypothetical scenario of severe economic and financial market stress. Qualitative factors include the strength of the firm’s capital planning process, which incorporate the risk management, internal controls, and governance practices that support the process. The Federal Reserve may object to a capital plan based on quantitative or qualitative concerns. If the Federal Reserve objects to a capital plan, a firm may not make any capital distribution unless expressly authorized by the Federal Reserve.

“Over the six years in which CCAR has been in place, the participating firms have strengthened their capital positions and improved their risk-management capacities,” Governor Daniel K. Tarullo said. “Continued progress in both areas will further enhance the resiliency of the nation’s largest banks.”

The Federal Reserve did not object to the capital plans of Ally Financial, Inc.; American Express Company; BancWest Corporation; Bank of America Corporation; The Bank of New York Mellon Corporation; BB&T Corporation; BBVA Compass Bancshares, Inc.; BMO Financial Corp.; Capital One Financial Corporation; Citigroup, Inc.; Citizens Financial Group; Comerica Incorporated; Discover Financial Services; Fifth Third Bancorp; Goldman Sachs Group, Inc.; HSBC North America Holdings, Inc.; Huntington Bancshares, Inc.; JP Morgan Chase & Co.; Keycorp; M&T Bank Corporation; MUFG Americas Holdings Corporation; Northern Trust Corp.; The PNC Financial Services Group, Inc.; Regions Financial Corporation; State Street Corporation; SunTrust Banks, Inc.; TD Group US Holdings LLC; U.S. Bancorp; Wells Fargo & Company; and Zions Bancorporation. M&T Bank Corporation met minimum capital requirements on a post-stress basis after submitting an adjusted capital action.

The Federal Reserve did not object to the capital plan of Morgan Stanley, but is requiring the firm to submit a new capital plan by the end of the fourth quarter of 2016 to address certain weaknesses in its capital planning processes. The Federal Reserve objected to the capital plans of Deutsche Bank Trust Corporation and Santander Holdings USA, Inc. based on qualitative concerns. The Federal Reserve did not object to any capital plans based on quantitative grounds.

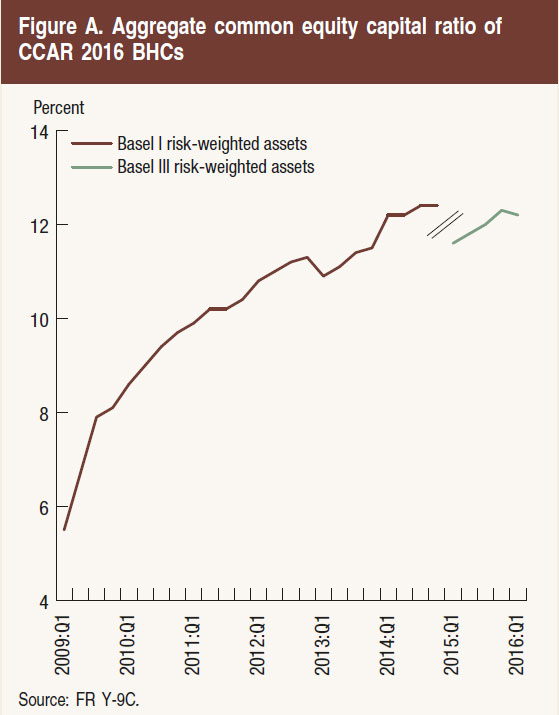

U.S. firms have substantially increased their capital since the first round of stress tests led by the Federal Reserve in 2009. The common equity capital ratio–which compares high-quality capital to risk-weighted assets–of the 33 bank holding companies in the 2016 CCAR has more than doubled from 5.5 percent in the first quarter of 2009 to 12.2 percent in the first quarter of 2016. This reflects an increase of more than $700 billion in common equity capital to a total of $1.2 trillion during the same period.