Glenn Stevens’ ten year stewardship of the Reserve Bank of Australia has been characterised by remarkable challenges. Yet, if the Australian economy has shown considerable resilience over this troubled decade, particularly during the global financial crisis, part of the credit certainly goes to the RBA.

When Stevens’ deputy, Philip Lowe succeeds him in September, he will need to continue to shepherd Australian prosperity through the challenges of global deflation and faltering global economic growth.

What direction will he take with the country’s monetary policy?

Glenn Stevens’ Legacy

Under Stevens, inflation has remained relatively stable and predictable, which is the main target for a central bank like the RBA. The repercussions of the financial crisis in North America and Europe have been mostly avoided thanks to the solidity of the Australian financial system, which is also a key responsibility of the RBA.

Sure enough, the exchange rate has experienced some wide fluctuations. But in an economy where the central bank targets inflation and there is no external anchor, these fluctuations are inevitable. In fact, the flexibility of the exchange regime has been another important factor driving Australia’s resilience.

Finally, the RBA has maintained its strong reputation and credibility both domestically and internationally; and in the current context where central banks in many industrial countries are blamed for poor macroeconomic management (well beyond their actual faults), this is no little achievement.

A solid background

A graduate from the University of New South Wales, Lowe holds a PhD from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He began his career with the RBA in 1980 and, until 1997, occupying a various positions in the International Department and Economic Group, before becoming Head of the Economic Research Department in 1997-98 and then the Financial Stability Department in 1999-2000.

In 2000-02 he was Head of Financial Institutions and Infrastructure Division at the Bank for International Settlements. After returning to the RBA, he headed the Domestic Markets and Economic Analysis Departments.

In 2004 he was appointed Assistant Governor (Financial System), then Assistant Governor (Economic) from 2009 until 2012, when he assumed his current position as Deputy Governor. This already impressive curriculum is enriched by several academic publications.

Lowe’s on monetary policy and financial stability

The RBA operates with an inflation target; that is, its objective is to use monetary policy to stabilise inflation at around 2%-3% on average over the business cycle. The pursuit of the inflation target requires the RBA to respond to demand pressures that can eventually lead to undesirable fluctuations in inflation and consumer prices.

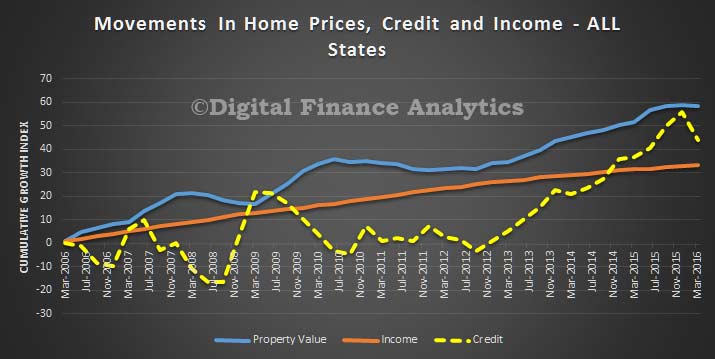

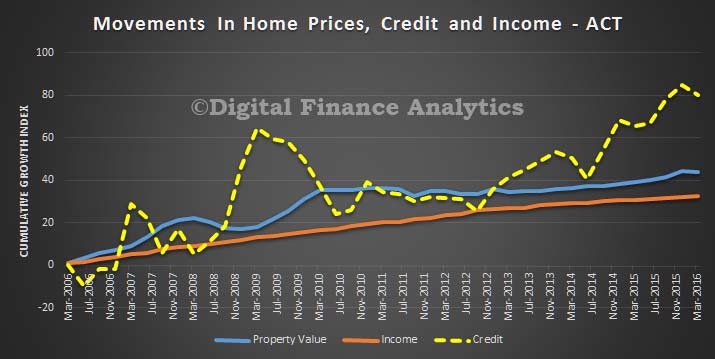

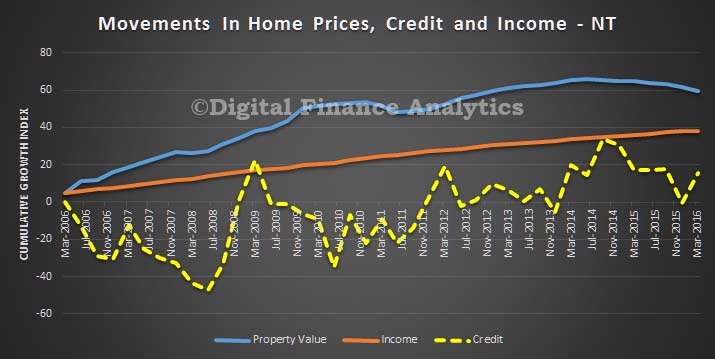

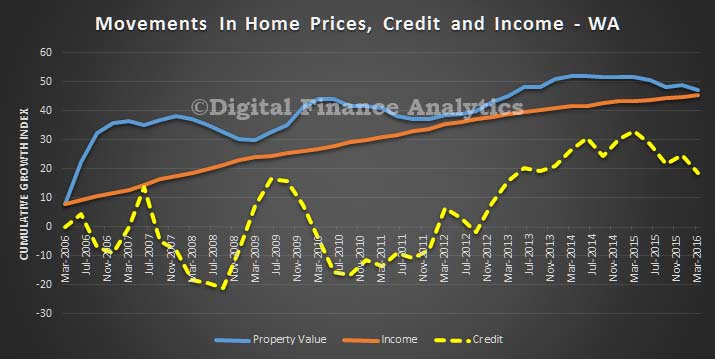

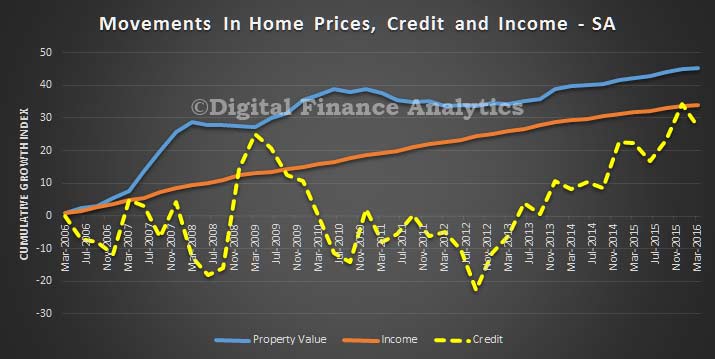

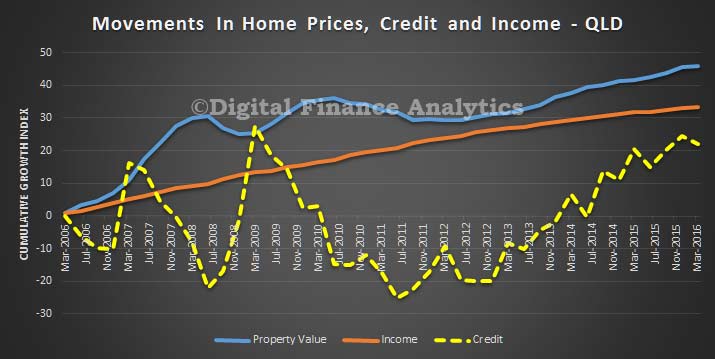

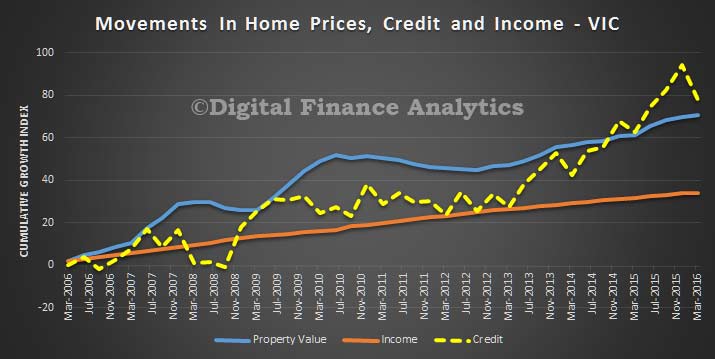

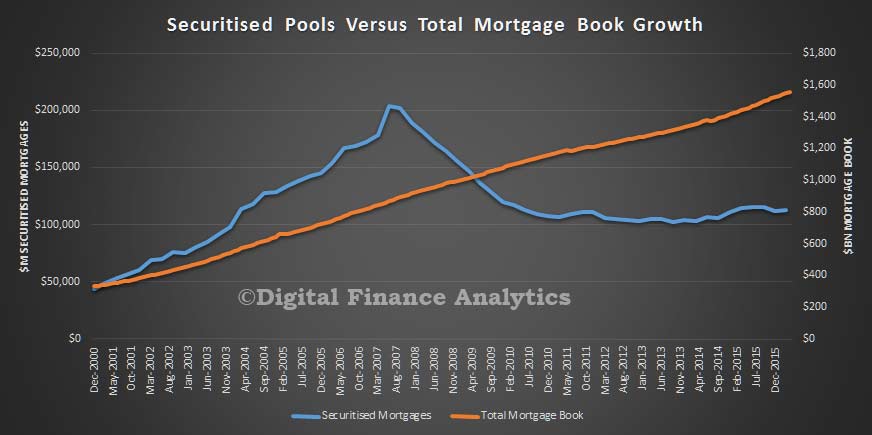

In a low inflation environment such as Australia, these demand pressures can manifest themselves in rapid credit and asset prices growth, which in turn trigger episodes of financial instability.

In some of his academic work, Lowe has documented these links, showing that inflationary pressures are likely to become evident in asset prices before they show up in goods and services prices.

Taken to the operational level, this means that the emergence of an asset-price bubble calls for a deflationary intervention of the RBA before the further enlargement of the bubble threatens financial and monetary stability.

We can therefore expect Lowe’s RBA to be watching credit and asset markets closely and be prepared to respond to fluctuations on such markets as a way to prevent a more general increase in consumer prices. To use an economist’s jargon, credit and asset markets become part of the monetary policy reaction function of the RBA.

But even under an inflation target regime, monetary policy should concern itself with the cycles of the “real” economy (that is, cycles of gross domestic product and employment). Provided that the inflation target is not compromised, monetary policy should be adjusted to stabilise cyclical changes in production and labour market conditions.

In fact, the RBA has never been the type of excessively hard-nosed central bank that exclusively pays attention to monetary stability. Even recently, monetary policy has been significantly accommodating, meaning that interest rates have been kept low as a way to support the cyclical recovery of the Australian economy.

This approach to monetary policy is very likely to continue under Lowe. For instance, in a recent address to Urban Development Institute of Australia (UDIA), he indicated that “[this] low inflation outlook provides scope for easier monetary policy should that be appropriate in supporting demand growth in the economy.”

In this regard, the challenge for him will be twofold. For one thing, as interest rates continue to decline, the effectiveness of further interest rate cuts in stimulating the real economy is likely to weaken. For another, a debt-obsessed government might end up relying too much on monetary policy and too little on fiscal policy to stimulate the economy.

This would then place the RBA in a difficult position, with Lowe having to protect the independence and autonomy of his institution.

Lowe’s on the long term prosperity of Australia

What else can monetary policy do for Australians? Someone might be tempted to argue that monetary policy should deliver long-term growth and prosperity.

In a sense, any public policy should aim at the greater good of the community. Monetary policy does that by delivering stable financial and monetary environment and by helping the economy to recover from short-term cyclical fluctuations.

But beyond that, prosperity becomes a matter of long term productivity growth and innovation, which in turn call for actions that fall largely outside the realm of monetary policy.

Sustaining productivity requires reforms to enhance competition, investment in transport infrastructure and in high quality education. Similarly, innovation stems from interventions that specifically support new entrepreneurial activities while preventing the distortions of old-school import substitution policies.

Active labour market policies are required to support the process of structural transformation of the economy and to guarantee that workers can relocate from declining to emerging sectors.

The RBA, or any central bank for that matter, is not meant to provide all that. In fact, expecting the RBA to do all (or even only some) of the above would tantamount to compromising its fundamental functions, throwing the Australian economy towards an era of financial and monetary instability and low economic growth.

In his October address to the CFA’s Australia Investment Conference, Lowe explicitly acknowledged that, ultimately, the rate at which living standards improve is unlikely to be driven by the actions of the central bank.

The hope is that the government will listen to him and take responsibility for bringing the Australian economy into a new era of prosperity.